Section Branding

Header Content

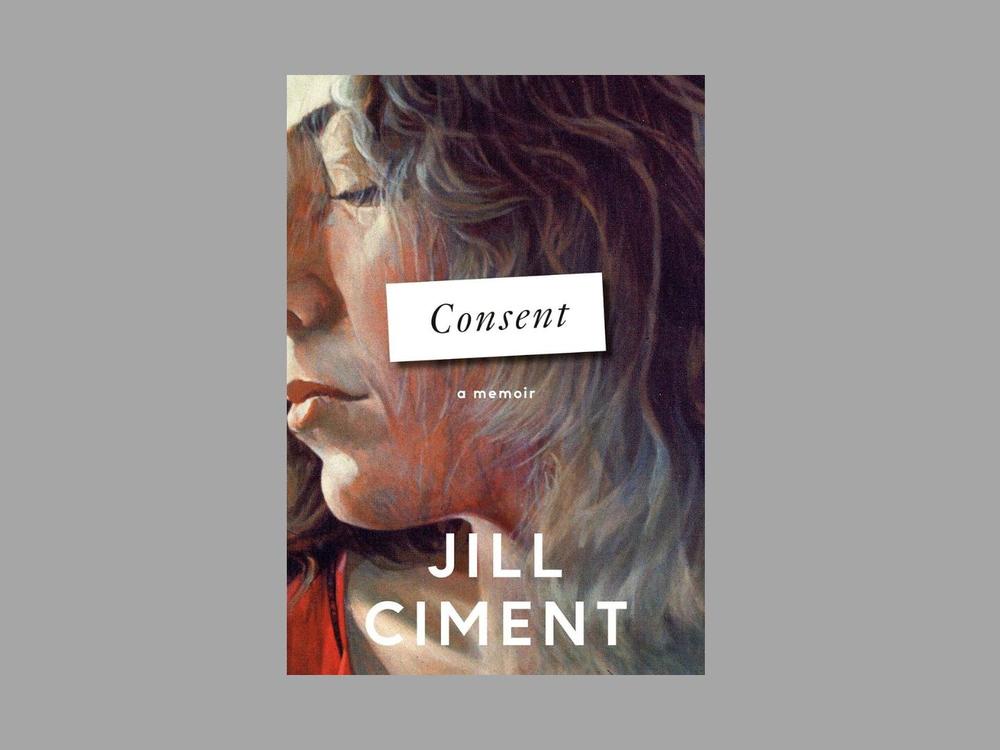

In 'Consent,' an author asks: 'Me too? Did I have the agency to consent?'

Primary Content

In 1996, novelist Jill Ciment published a memoir called Half a Life. It is primarily about her hardscrabble childhood in California's San Fernando Valley, dominated by her difficult, volatile father, whom Ciment realized in hindsight was autistic. But about halfway through, Ciment's life takes a turn, when at 16, she signs up for figure drawing classes, which she pays for with earnings from a part-time job. She develops a crush on the teacher, a married artist 30 years her senior named Arnold Mesches. Within a year, they are having an affair. Or, as she puts it, "Arnold was having an affair. I was going steady."

That relationship is the subject of Ciment's follow-up memoir, Consent. Half a Life was written when she was in her 40s and Arnold (as she refers to him) was in his 70s -- at which point they had been married for more than 25 years. Now, eight years after his death at 93, she reconsiders their relationship in light of the #MeToo movement.

Her remarkable new book -- at once forthright, thoughtful, and moving -- broaches many questions: "Does a story's ending excuse its beginning?" "Can a love that starts with such an asymmetrical balance of power ever right itself?" "How do I convey yearning for a kiss while at the same time acknowledge the predatory act of an older man kissing a teenager?"

You don't have to read Half a Life to appreciate Consent. In fact, the second memoir, which both scrutinizes and amplifies what Ciment first wrote about her relationship with Arnold, is a far more interesting book.

She describes their first kiss differently in the two memoirs. In the earlier version, she initiated the kiss and Arnold kissed her back, but then stopped himself and said, "Sweetheart, I can't sleep with you. I'd like to, but I can't...It wouldn't be fair to you." In the new book, he draws her to him and kisses her, and "I fervently kissed him back."

The age of consent in California is 18. Had Arnold groomed her with extra attention in class, or with furtive glances down her blouse? What about whispering to her, "I wish you were older"? Her reply in both books: "I'm old enough."

"Me too?" she wonders now. "Did I have the agency to consent?"

Arnold read and discussed the first memoir with her -- commenting, for example, that he would never have called a student "sweetheart." But he was not alive to respond to Consent, and Ciment tries to imagine his reactions.

She questions her earlier assertion that she would never love anyone more than Arnold: "Could I have felt so sure of my love at 17 that I knew nothing would surpass it? Or was my 45-year-old self, in the middle of the marriage and the memoir, trying to burnish the story with love lest it read like a reenactment of Humbert Humbert and Lolita's cross-country road trip?" Was she protecting Arnold, even though the statute of limitations had long passed?

In a particularly astute passage, Ciment highlights how language reflects changing social attitudes and colors our views -- which makes it difficult to judge past behavior by today's moral codes:

"If Arnold kissed me first, should I refer to him in the language of today --sexual offender, transgressor, abuser of power? Or do I refer to him in the language of the late 90s, when my 45-year-old self wrote the scene? The president at that time was Clinton, and the blue dress was in the news. Men who preyed on younger women were called letches, cradle-robbers, dogs. Or do I refer to him in the language of 1970, at the apex of the sexual revolution, when the kiss took place -- Casanova, silver fox?"

Time also alters the words that might be used to describe teenaged Ciment: a victim or survivor in today's parlance, a bimbo or vixen in the 90s, a cool chick in the 70s.

It turns out there was plenty Ciment omitted in Half a Life, including uncomfortable details like the fact that Arnold had not just a wife but another longstanding mistress when they first got together. And that, ever the teacher, he instructed her on sexual techniques and helped her prepare a portfolio of explicit sexual drawings from the female point of view for her application to CalArts school.

These early elisions provide a pointed reminder that all writing is selective, and memoirs are certainly no exception.

Ciment's frankness extends to the disadvantages of being a much younger wife, including Arnold's inevitable physical diminution, the constant specter of loss, and -- more amusingly -- being asked how much she's paid to take care of the old man dozing on a park bench beside her. You don't have to be a Freudian to note that in Arnold, who was the same age as her father, Ciment found an attentive paternal figure who "showed me who I might become."

But Consent -- whose working title was The Other Half -- makes clear that she found much more. Their "half century of intimacy" included physical and mental stimulation, companionship, power shifts, financial worries, successful creative careers, illnesses, and, through it all, artistic collaborations in which "he was my first audience, as I was his first viewer."

Despite their many conversations about the subject, they never reached a firm consensus about who initiated that first kiss. No such uncertainty exists about their heartbreaking last one. This is a book poised to fuel plenty of discussion.