Caption

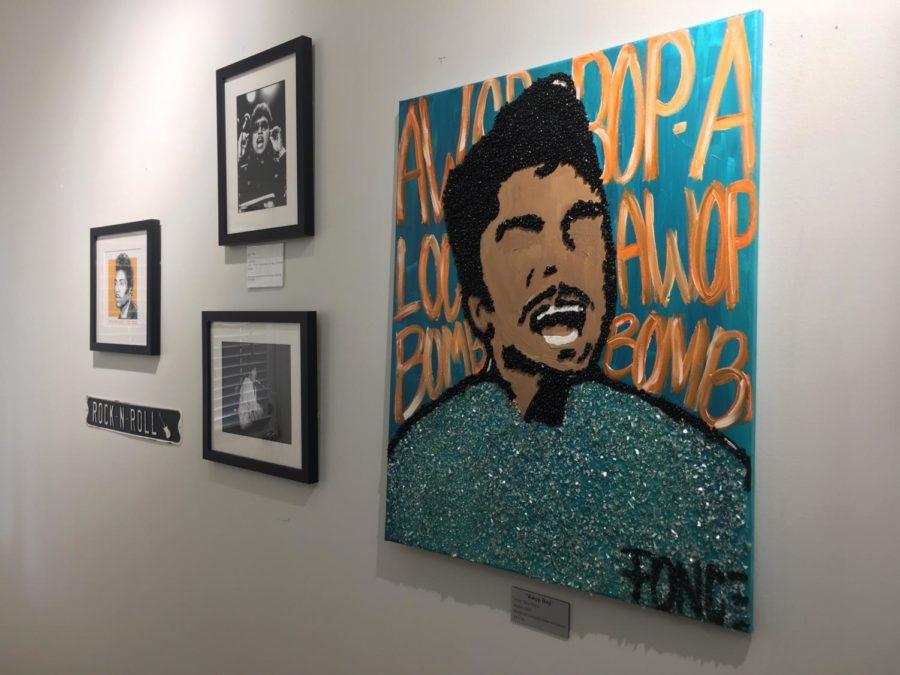

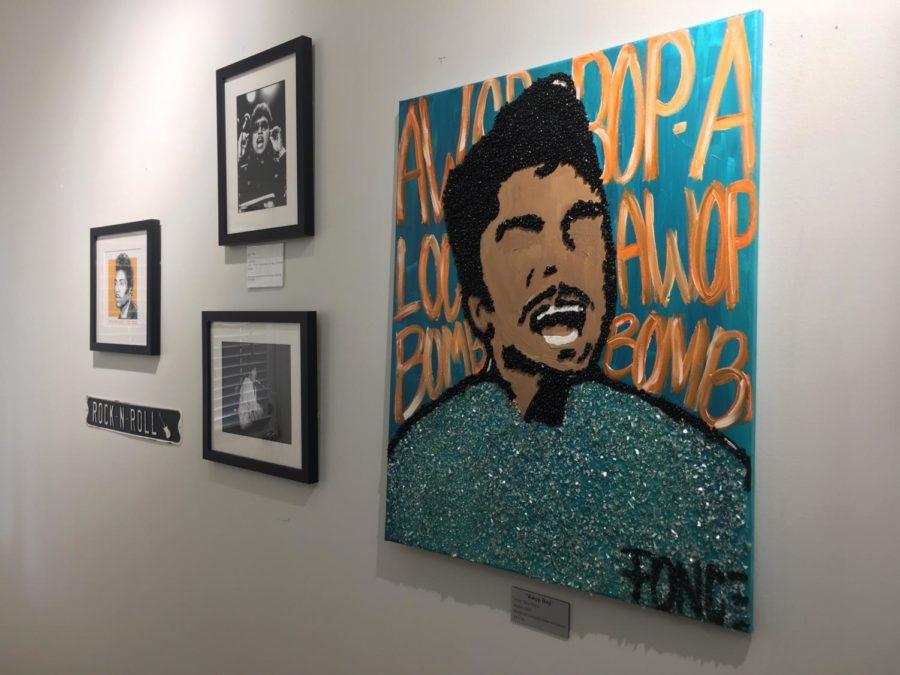

Images of Macon’s famed showman line the hall of the Little Richard House in Pleasant Hill.

Credit: Liz Fabian / Macon Newsroom

Images of Macon’s famed showman line the hall of the Little Richard House in Pleasant Hill.

The Little Richard Neighborhood Resource Center closed indefinitely without fanfare or public notice last weekend.

A few days later, the historic childhood home of Macon music legend Little Richard sat silent, save for the occasional thunk of moving boxes being unfolded by a man whose last day on the job is June 7.

The pause of operations comes after months of back-and-forth between the Macon-Bibb County government, which owns it, and the Macon-Bibb Community Enhancement Authority, CEA for short, which operated it on behalf of the county. At the heart of the issue is an unmet requirement for the CEA to provide a financial audit and receipts showing how the money was spent.

The small yellow house at 416 Craft St. opened to the public in 2019 as a resource center for residents of Pleasant Hill. The historic Black neighborhood was split in two by the construction of Interstate 75 in the 1960s.

“Hopefully it’ll be under new management,” resource house manager Robert Banks said, adding that it will be his last week working for the authority. “I was told that we were going to get everything together and figure it out … it should have never got to this point.”

According to letters obtained by The Macon Newsroom through an open records request to the county, funding for the resource center stopped late last year when the county put CEA on notice for violating the management contract.

The county has paid the authority $96,000 yearly to manage the resource house. The contracts stipulate unused money is to be returned to the county, along with financial audits and detailed monthly expenses showing how the money was spent.

But public records show the authority has never returned unused money to the county and it never provided a financial audit or detailed reports showing how the money was spent.

In a letter to authority board chairperson Bruce Riggins on Dec. 22, Macon-Bibb County Attorney Michael McNeill wrote the county is “suspending any future payments to the CEA until all the requirements of the agreement have been met” and “will not enter into a funding agreement with the CEA for fiscal year 2024 until the CEA has come into compliance with the terms of the last agreement.”

Riggins wrote McNeill back in early January and said the board had been working to untangle its finances for more than a year and even “refused to sign the contract presented by the previous director until proper budget and financial accountability mechanisms were established.”

“We are committed to rectifying our past deficiencies and moving forward with greater fiscal responsibility,” Riggins said in the January letter.

In late March, Riggins wrote McNeill another letter communicating the “critical need for sustainable funding to support continued management” of the house.

“Despite the lack of funding received since November, we have endeavored to keep the Little Richard House in operation, understanding its significance to our community,” Riggins said in the March letter. “Regrettably, if we cannot find a prompt and satisfactory resolution to this matter, we have no choice but to discontinue our management of the Little Richard House effective 3/31/2024.”

Mayor Lester Miller agreed to provide the authority with funding to keep it operating through May, allowing the authority two more months to provide the financial audits and expense details to come into compliance with its previous contracts.

However, the authority still has not conducted a financial audit. It’s something Riggins said the authority can’t afford.

As Banks packed up boxes Wednesday, the authority’s interim executive director, Latisha Woods, said the authority closed the center because it “didn’t have verbal or written commitments or assurances of what the future was supposed to look like” despite several discussions with the county.

Woods said the authority provided the county with expenses showing “what justifies this amount of funding.” The $8,000 monthly from the county covered utilities, payroll and maintenance, she said. Even so, terms of the contract have not been met because the authority has never undergone a financial audit.

“I’m hopeful that something else will happen to kind of turn that tide, whether it be with us or not,” Woods said.

It is unclear what the future holds for the former childhood home of the world-renowned musician known as the “architect of rock ‘n’ roll.” Portraits of Richard Wayne Penniman are hung on the walls with displays including artifacts from his career.

“It is our hope and desire the CEA will supply the necessary audits and resume operation,” Mayor Lester Miller said in a typed reply to The Macon Newsroom on Thursday. “However, we will take the steps necessary to ensure it remains a resource center for the community. We do not know yet what that looks like but we want it to be something the neighborhood and community find valuable.”

The yellow house was originally located on Fifth Avenue, just east of Interstate. In 2017, as the Georgia Department of Transportation prepared to expand the interchange at I-75 and I-16, the house was cut into parts, loaded onto trucks, moved to the east side of the interstate where it was rehabilitated.

The Little Richard Community Resource Center.

Its use as a neighborhood resource center was among several promises GDOT made to the neighborhood in an agreement on the Pleasant Hill Mitigation Plan, an environmental justice project meant to offset harm to the neighborhood that resulted from the original interstate construction and further encroachment from the current expansion project.

In early March, the CEA moved out of the Booker T. Washington Community Center, which it also was contracted to manage on behalf of the county. The CEA currently operates out of the nearby Triangle Business Center on Georgia Avenue.

The Macon-Bibb County Community Enhancement Authority was created through a state bill introduced by Rep. James Beverly, D-Macon, during his first legislative session as a state politician. The authority’s sole mission is to reduce poverty in the poorest neighborhoods in Bibb County.

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with The Macon Newsroom.