Caption

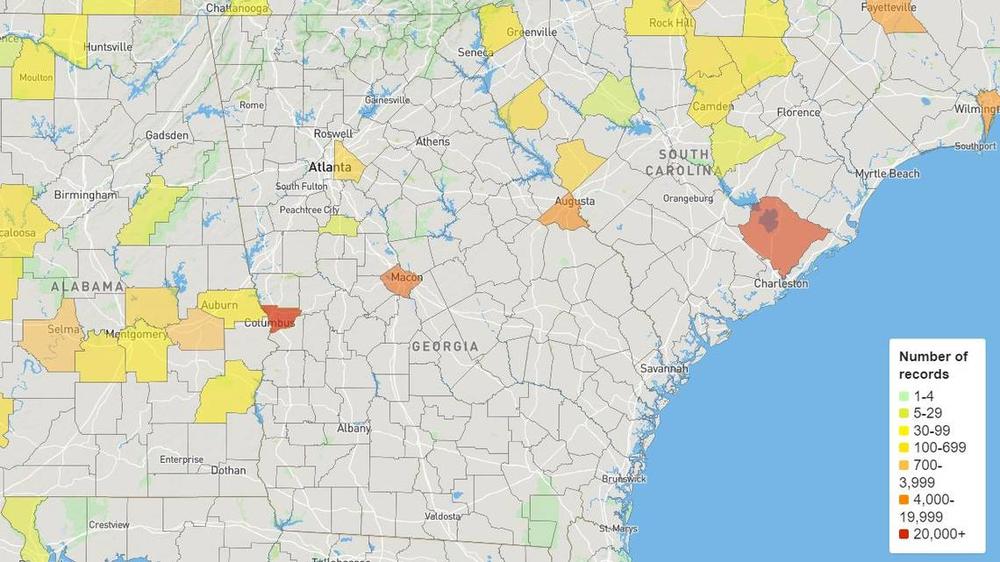

This map from Ancestry, one of the world’s largets genealogy companies, shows the number of records found in different Georgia regions for the company’s project to find newspaper records on enslaved people. More than 22,000 former enslaved people’s names were found in Columbus records, the company says.

Credit: Ancestry