Caption

The door to the counseling office at Roswell High School stand open on a late spring 2024 day. Inside, the walls frame the open space with encouraging and colorful signs under soft lighting.

Credit: Ellen Eldridge / GPB News

LISTEN: The need for school-based trauma-informed care that addresses grief, addiction, and suicide prevention has grown tenfold amid the coronavirus and opioid epidemics. Providers are struggling to meet the demand for mental health services — even in affluent areas. GPB’s Ellen Eldridge has more.

The door to the counseling office at Roswell High School stand open on a late spring 2024 day. Inside, the walls frame the open space with encouraging and colorful signs under soft lighting.

Despite having some of the best available resources in affluent and connected communities, students are struggling to access enough mental health help.

That includes Roswell, a suburb north of Atlanta.

Two weeks after a teacher unexpectedly died last year, a Roswell High School student died by suicide.

Keaton Warner, a licensed practical counselor with CHRIS 180, said the back-to-back tragedies hurt the entire student body.

"After that we had a really big need," Warner said. "We had a really big push and a really big influx of students who needed to come to us, because a lot of the parents saw that as a situation of like, 'Wow, I need to actually pay attention.'"

The door to the counseling office was open on the recent last day of school.

Inside, the walls framed the open space with encouraging and colorful signs. Soft light fell across beanbag chairs and a plush couch with pillows shaped like plants.

It’s the kind of room where one could exhale. And then breathe again.

COVID trauma is connected to anxiety and depression among students in Roswell, student counselor Jill Canada said.

"Like it's still following us," Canada said. "And I think we have forgotten that a little bit. But, like, those losses that happened four years ago are still just as real for a lot of people. Those near-losses are still just as real."

Between January 2020 and May 2022, COVID-19 killed an estimated 216,617 family and in-home caregivers.

That means, nationwide, one out of every 336 children under the age of 18 experienced the death of someone in their home who cared and provided for them.

More than 3,500 Georgians died from COVID-19, according to the state Department of Public Health.

Some of the first students Warner spoke with when he joined Roswell High School had lost parents to COVID.

"That grief was so deep and so new because the pandemic was so recent," he said. "We didn't really know how to handle that type of situation outside of just normal grief therapy."

So that's what they did — they set up something more.

Valerie Rogers, the school’s longtime social worker, advocated for more school-based therapists as the pandemic began.

Four years ago, Roswell High School contracted with CHRIS 180, a social services organization in neighboring DeKalb County, to provide school-based mental health services at no cost to the students.

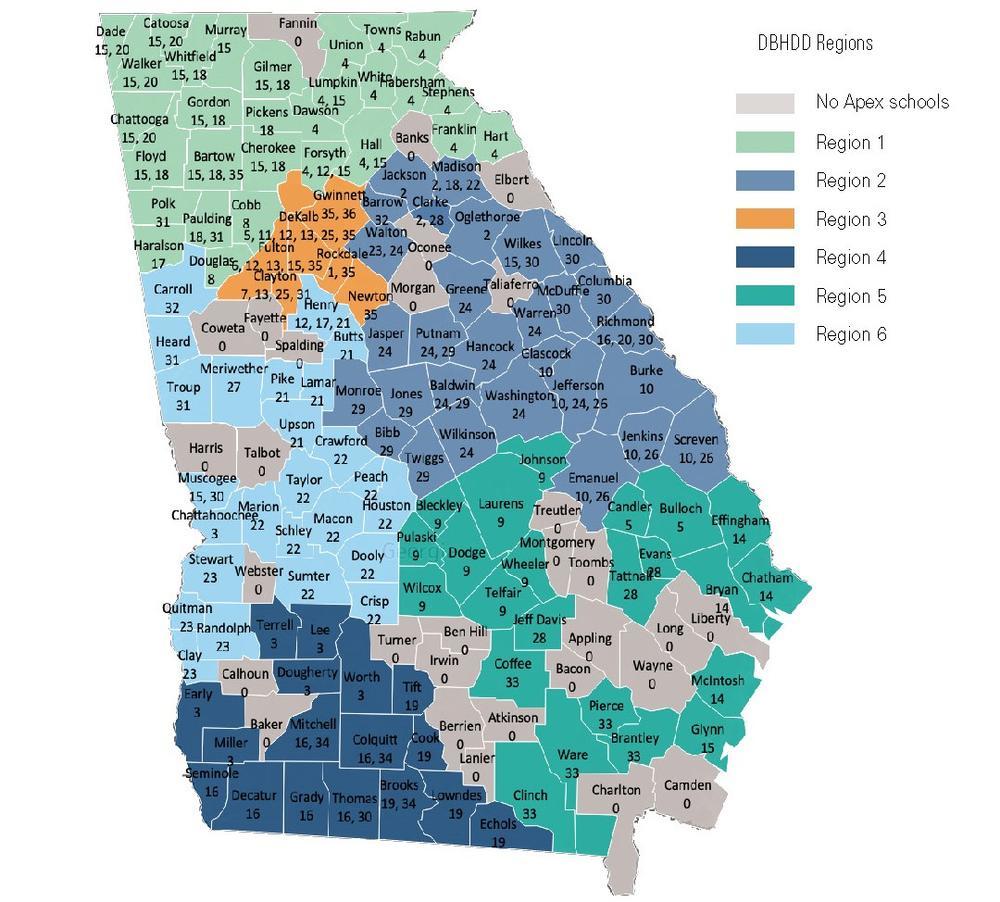

The nonprofit is funded through the Georgia Department of Behavioral and Developmental Disabilities (DBHDD) APEX program, the Department of Justice, Purpose Built Schools Atlanta, Fulton County DBHDD and United Way of Greater Atlanta.

Canada thinks their more affluent community is supportive of mental health in particular because it has affected so many different people.

"We have lost a number of students over the past 10 years to suicide," she said. "And so I think our entire community is very connected to as much mental health and as much conversation as we can have around it."

Despite their excitement, it's not enough. There is always a waiting list for counselors.

"We could have a whole wing of therapists here," Rogers said. "We would love to have a therapy wing, because we could fill it."

Valerie Rogers has been the social worker at Roswell High School for 20 years.

The pandemic was hard enough on kids' physical, economic and mental health, but the opioid crisis emerged into an epidemic alongside the novel coronavirus.

Four months into COVID's arrival in 2020, addiction experts warned of the effects of isolation on people struggling with substance misuse.

Not long after the data became available, those experts were disappointed to learn how correct they were.

More than 320,000 children across the country lost a parent to a drug overdose between 2011 and 2021, according to a new study published in JAMA Psychiatry.

That's a 134% rise in the rate of children whose parent died by overdose during the study period — from 27 per 100,000 children in 2011 to 63 per 100,000 in 2021.

Canada said her goal in school is to guide all students as they process their grief, anxiety and depression to get back to who they want to be.

"Get them back on track," Canada said. "Because sometimes this grief, I mean, it's complicated, it's confusing. It throws off their entire world."

The school showed students and made available for parents screenings of the movie ScreenAgers: Under the Influence, which specifically targets how teenagers are exposed to THC and fentanyl.

Rogers wants the counselors to teach students basic coping skills to be able to function in life.

"They're exposed to so much more than they ever have been before, and it is skyrocketing." Rogers said. "The things that we're seeing children are exposed to and experimenting with have really changed a lot in the last five years much less than 20."

When students (and all people) discover how to deal with their anxiety, thoughts of depression and suicidal ideation, they won't need to take poor advice from friends or social media, she said.

For many students, Rogers said, the challenge is establishing a healthy normal.

"I think that students come lacking the internal skills to be able to self-regulate and that they are choosing unhealthy coping mechanisms," Rogers said.