Section Branding

Header Content

Pluto isn’t a planet — but it gives us clues for how the solar system formed

Primary Content

This story is part of Short Wave's series Space Camp about all the weird, wonderful things happening in the universe. Check out the rest of the series.

If you were born in the last century you might have memorized that there were nine planets in our solar system, as heard in the famous Schoolhouse Rock! song, Interplanet Janet. Upon the discovery of its existence in 1930, Pluto enjoyed decades of special status as one of the solar system's planets.

Then, in the summer of 2006, Pluto was demoted.

Part two of Short Wave's series Space Camp looks into this demotion from "planet" to "dwarf planet." It's a shift that on its face might seem slight — all that's happened is the word "dwarf" was added in front of "planet." But Wladimir Lyra, a computational astrophysicist at New Mexico State University says that although "planet" and "dwarf planet" sound similar, comparing a dwarf planet to a planet is similar saying that a pineapple is a type of apple. Which is to say, it is not really the same at all.

What makes a planet?

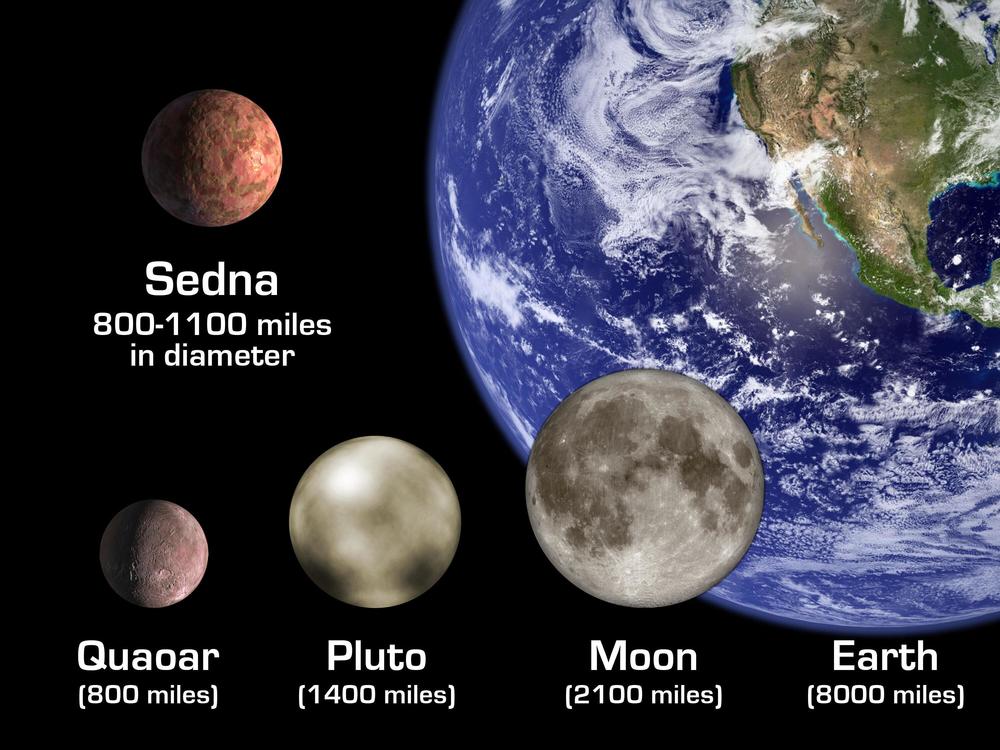

At the 2006 meeting of the International Astronomical Union in Prague, 424 members representing over 10,000 scientists passed a resolution to decide what the word ‘planet’ would actually mean in our solar system. This decision was prompted by several objects the size of Pluto being discovered in the early 2000s — Eris, Sedna and Quaoar. Pretty quickly a debate emerged: Would these newly discovered objects all have to be called planets?

This wasn't the first time such a debate happened. The discovery of Ceres in the early 1800s prompted debate among scientists.

Ceres is the largest known object to exist in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. In fact, Ceres makes up 25% of the total mass of the asteroid belt. Still, Ceres remains a dwarf planet. Perhaps as it should, given Pluto's relegation to dwarf planet — Pluto is 14 times larger than Ceres.

Both Ceres and Pluto are given this designation because they do not meet the criteria for being a planet that were created in that 2006 IAU meeting. There, it was decided that in order for an object to be considered a planet in our solar system, it must:

- Orbit the sun

- Be massive enough to be mostly spherical

- Clear the neighborhood around its orbit (This basically just means that it can't be located near a bunch of asteroids or bits of rock or ice.)

All of this technicality appears to be moot for residents of Arizona: In April 2024, Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs signed a bill making Pluto the state's official planet.

It is also moot to some planetary scientists. Some planetary scientists suggest changing the definition of a planet to be more focused on geology. This alternative geophysical definition of a planet basically proposes two criteria for an object to be considered a planet:

- There isn’t fusion happening — like with stars

- The object has enough mass to be spherical

By this geophysical definition, Pluto would be a planet again.

Planetary insights from a dwarf planet

Planet or not, Pluto is useful for understanding how planets form. “As a scientist who studies how planets form, Pluto is a brick that helps me understand the building,” says Lyra.

For Pluto and the 8 planets, this process begins with clouds of gas and dust in space. Once dust enters a disk of gas orbiting a star, Lyra says that a kind of coagulation happens. That coagulation creates larger "grains" of dust, "a bit like if you don't clean your room often enough — you're going to get dust bunnies, right? Now imagine you don't clean your room for 10 million years." Eventually, forces like gravity will cause the material inside the disk to concentrate those grains and create asteroids, dwarf-sized planets — and eventually a planet.

Astronomers call these "planetesimals," a portmanteau of "planet' and "infinitesimal." It hints at the fact that these are very small parts of a planet — or as Lyra likes to call them, the "building blocks" of planets.

If the disk is colder and far enough from its star that water can freeze, then tiny fragments of ice can hang out with the dust and become giant planetary cores. These cold regions slow down gas molecules enough to be sucked in. It's how scientists think the gas giants — Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune — were formed.

The complex geology of Pluto also tells us about the early solar system.

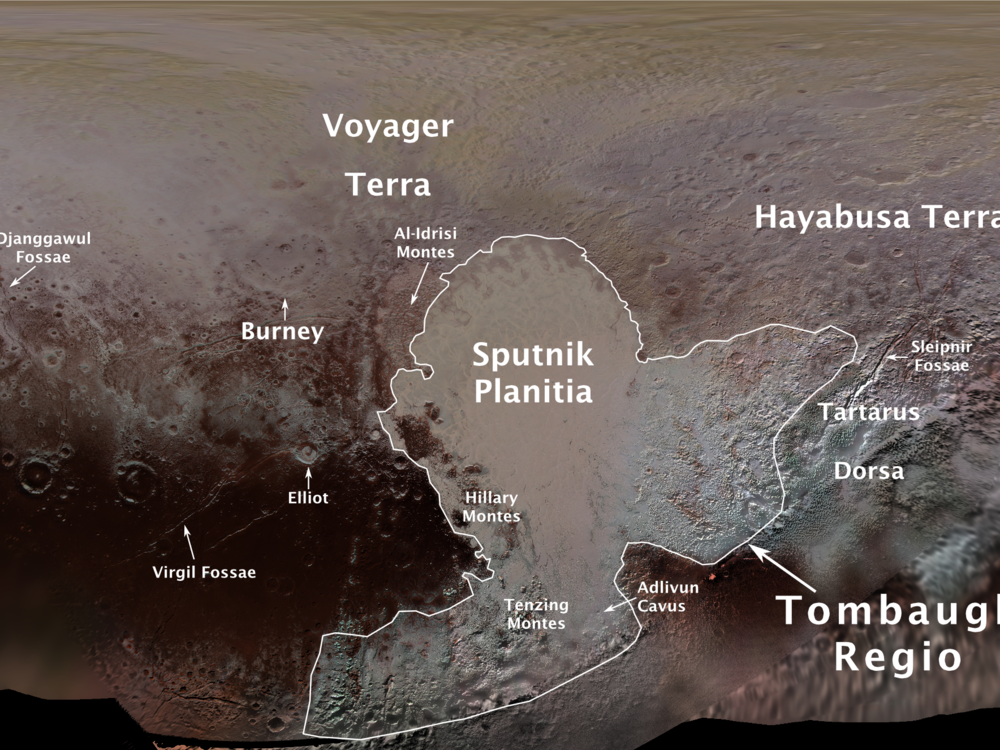

The surface of the planet was documented by NASA’s New Horizons mission, which flew by in 2015. It found icy mountains, volcanoes that may spew ice and a large heart-shaped feature on the dwarf planet’s surface. In the upper left of that feature is Sputnik Planitia, which scientists think may hold a giant subsurface ocean. Based on the material on the surface, this ocean would contain a mix of nitrogen, carbon monoxide and methane. But the small bodies around Pluto’s orbit in the Kuyper belt do not share this mixture. That makes scientists think that Pluto formed elsewhere — and adds nuance to their understanding of how the solar system formed.

Given these connections, Lyra is in favor of the geophysical planet definition. He says that instead of limiting planets to only eight in the solar system, we could include all of the dwarf planets and even moons.

He says he often gets the question, “How will children memorize all these new planets?” in response.

He answers the question with one of his own: “Can you tell me the the the lineup of the the U.S. women's soccer team?”

The answer for many of us is no. That's exactly his point. Just because you can't name all the players — or the planets under this reclassification — doesn't mean they're less important.

Plus, it would mean an interesting update for Earth: Just like there are binary stars, Lyra says Earth and its moon would newly be considered a binary planet system.

More from Space Camp

This story is part of Short Wave's Space Camp series about all the weird, wonderful things happening in the universe. Check out more from the full series:

More from Short Wave

Questions about the state of our universe or smaller happenings here on planet Earth? Email us at shortwave@npr.org — we'd love to consider it for a future episode!

Listen to Short Wave on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

Listen to every episode of Short Wave sponsor-free and support our work at NPR by signing up for Short Wave+ at plus.npr.org/shortwave.