Section Branding

Header Content

'Emergency Quarters' are for pay phones (remember those?) in a new book by ‘90s kids

Primary Content

A couple of years ago, Carlos Matias was living in Florida and feeling nostalgic for his hometown.

“I just started writing little short stories about New York,” Matias says. “And then I started submitting them to the New York Times Metropolitan Diary.”

His short story, Emergency Quarters, became a “Best of the Year” finalist in 2021 and this year, a children’s book.

“Growing up, when I first started to walk to school by myself, my mom would give me a quarter every single day,” Matias says. She’d tell him, “‘If you need me, or if you're going to come home late, or if you're going to hang out with your friends, give me a call and let me know.’ So I was a young Carlos running around with a bunch of quarters in his pockets back in Queens.”

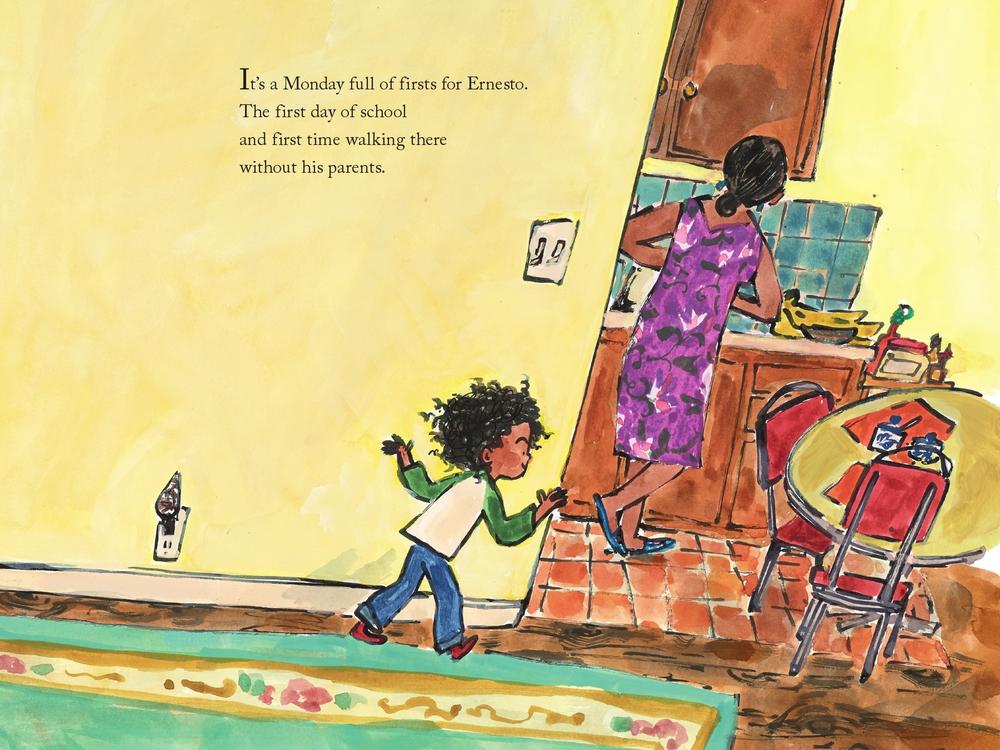

Emergency Quarters is about a little boy named Ernesto who, like Matias, gets to walk to school without his parents for the first time.

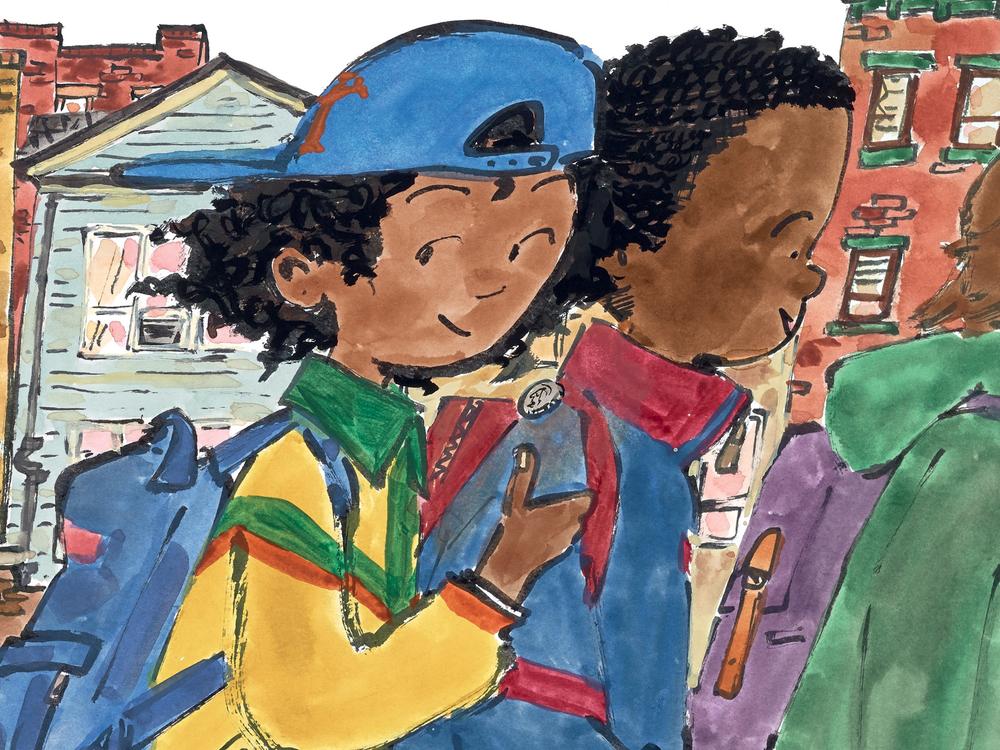

Ernesto throws on his lucky kicks and his favorite Mets cap.

“Feelin’ freshhhh!” he says to the mirror.

But before he can sneak out the door, his mother stops him.

“For emergencies, Ernesto,” she whispers, covering his right hand with both of hers. “If you need me, look for a pay phone.”

A what?

“When I do story times and stuff, I have to always start off with asking the kid, ‘Do you know what a pay phone is?’ And I get the funniest answers,” laughs Matias.

If anyone reading this doesn’t know what a pay phone is — send a telegram to NPR headquarters and someone will get back to you. They might be few and far between now, but when Matias was growing up in the 1990s, payphones were on practically every street corner. At the peak, the FCC says there were more than two million in the United States. But by 2016, there were fewer than 100,000 in service.

“This one was a really fun one to work on,” says Gracey Zhang, who illustrated Emergency Quarters. “I think because we’re both '90s kids.”

To bring Matias’ childhood to life, Zhang worked traditionally, starting off with pencil sketches. Then, on huge pieces of paper, she used black ink for the line work and gouache paints for the color. “I like to work bigger than the book is actually being published,” Zhang explains. “So that when it’s scanned, the image is not blown up, but it’s shrunken down.”

Her guiding light for the color palette, the feel of the book, was another staple of the '90s: the windbreaker. You know the kind. Shiny, swooshy. Bold, saturated colors.

“For each book that I work on, I kind of like to focus on a specific feeling or object that I want to evoke,” she explains. “This story has almost — think '90s sitcom show colors. That kind of informed a lot of the clothing that the characters wear.”

For research, Zhang also did some — gentle — stalking of Matias’ childhood photos on the internet. And Matias sent along some shots of his neighborhood — Corona, Queens.

Queens is colorful — and detailed — in Zhang’s paintings. The streets are crowded, the arcade has purple-checkered floors, Señora Mayra’s fruit stand umbrellas are tropical blue, pay phones (of course) dot the landscape, and you can practically hear the 7 train roll through the neighborhood.

“Living in New York, I’m very particular about the subway train depictions,” says Zhang. “I spent like, way too long just making sure I had the right train — the model of the train, the line.”

“One thing people always mention that are from Queens are like, ‘Oh my god The Lemon Ice King, the Dominican fritura restaurants,” says Matias. “So the fact that those actually made it on there, these famous places, that was pretty cool.”

On Monday, Ernesto and his friends visit Señor José’s bodega. His friends buy cheese puffs and gummy worms, but Ernesto saves his emergency quarters. On Tuesday, they go to Manny’s Video Games, but Ernesto doesn’t play any games. That night, he asks his mom why he doesn’t have as many quarters as his friends. She tells him that fewer quarters means each one is special — kind of like limited-edition baseball cards.

“On Wednesday morning, he can feel his three quarters jingling in his pocket all the way to school,” Matias writes.

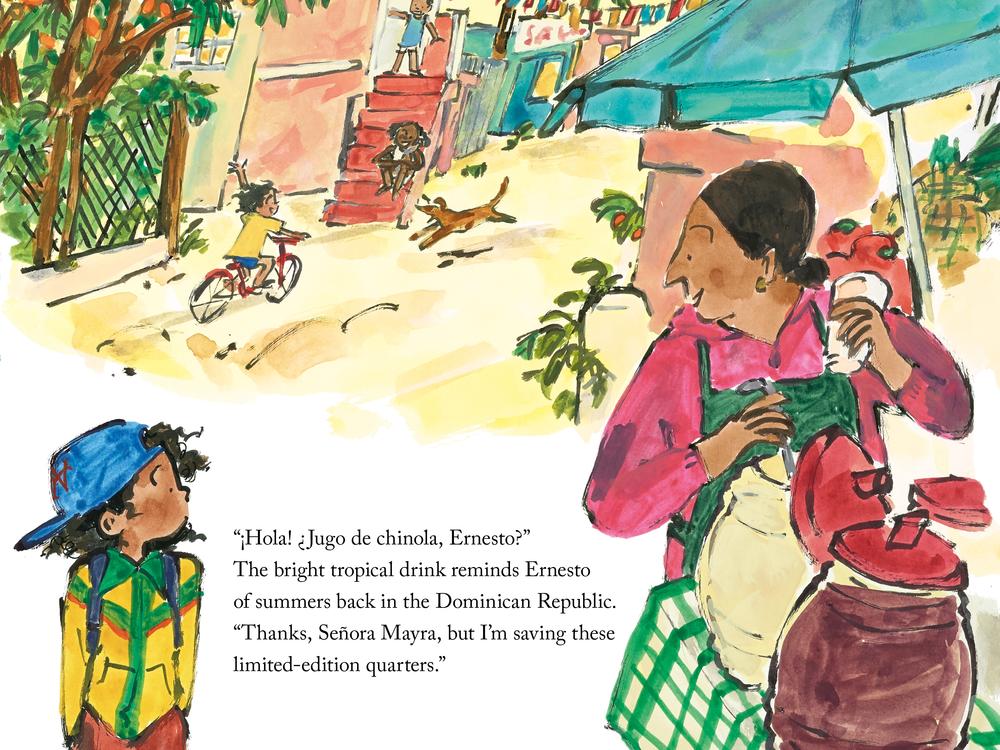

“¡Jugos de frutas! Seventy-five cents!” Ernesto loves Señora Mayra’s fruit juices; they make him big and strong.

“¡Hola! ¿Jugo de chinola, Ernesto?”

The bright tropical drink reminds Ernesto of summers back in the Dominican Republic.

“Thanks, Señora Mayra, but I’m saving these limited-edition quarters.”

“Such restraint at a young age,” laughs illustrator Gracey Zhang. “My mom did not trust me with any coins. I would just like, rummage through the house for whatever spare coins to buy myself my own snacks.”

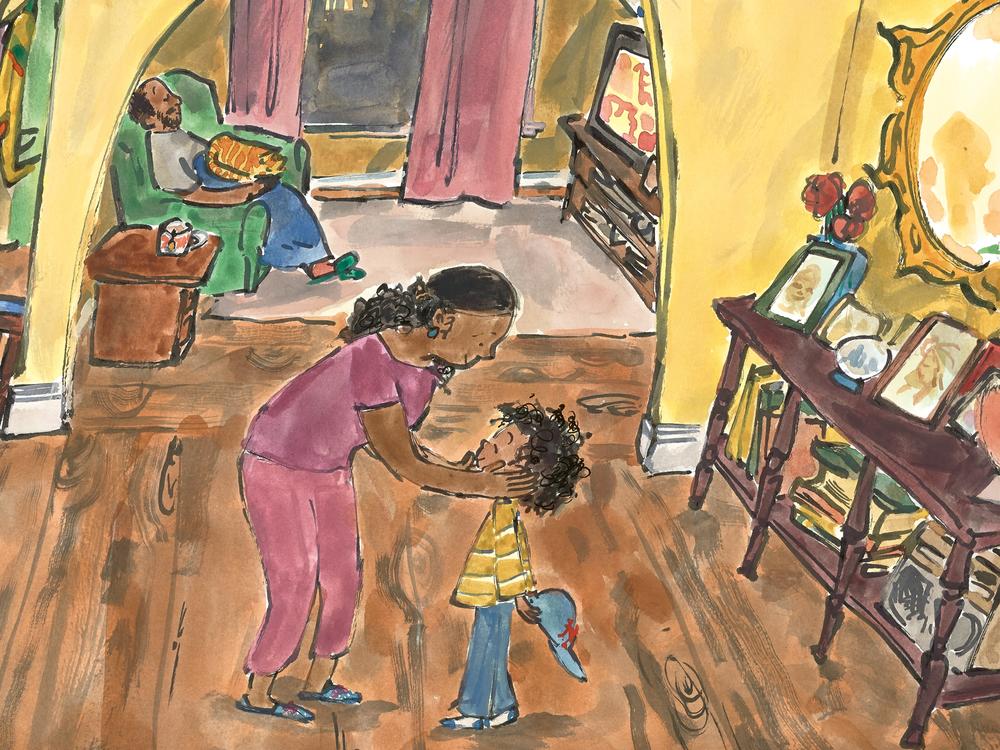

Nevertheless, Zhang says she felt a connection to Ernesto. Before she lived in New York City, she grew up in a small town outside of Vancouver, Canada, where she also walked to school on her own, just like Ernesto. Except they didn’t even have any pay phones. “There was just this period where kids almost had less distractions,” she says. “So this sort of young independence really spoke to me.”

“True,” adds author Carlos Matias. But — he points out — what Ernesto has is actually the best of both worlds. Because, as he writes in the book, the mother is never very far away. Ernesto can be independent and experience the world while also knowing that his parents are only an emergency quarter call away.

And if it happens to be an empanada emergency…