Section Branding

Header Content

Removing the highway is the easy part. Reconnecting the community is harder.

Primary Content

DETROIT – In the 1950s, When Regina Lawson was a girl on Detroit’s east side, she would walk along Hastings Street every day with her father.

“From the barber shop to the grocery store to the pharmacy, everything was right on that strip,” she says, in the lobby of the senior apartments where she lives now, not far from where Hastings Street used to be.

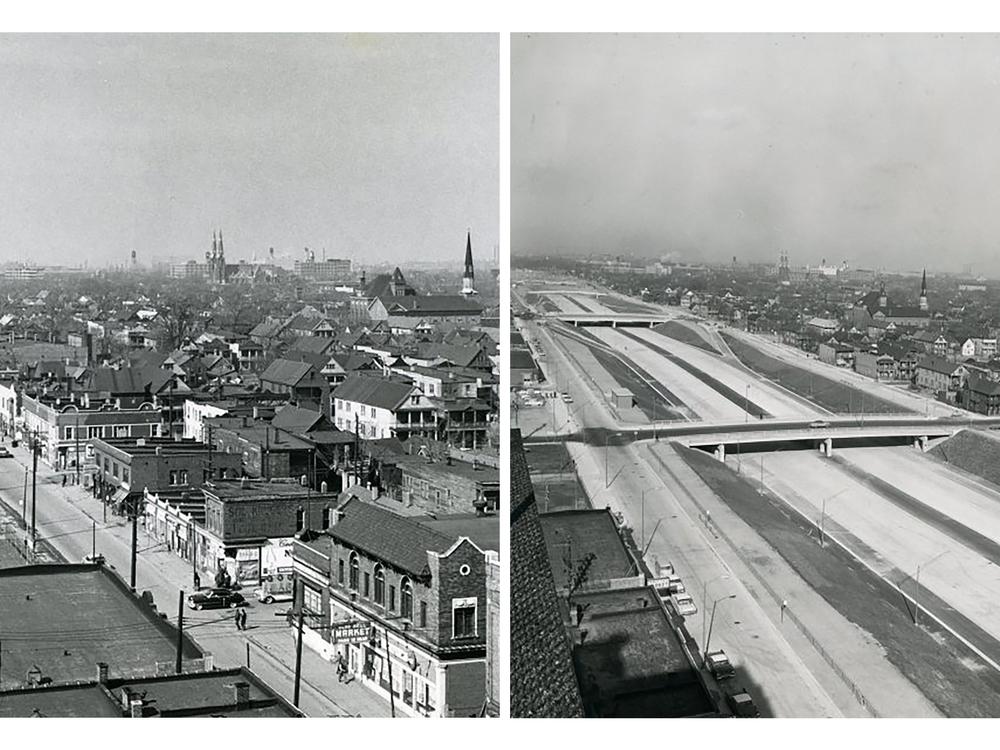

But Hastings Street disappeared some 60 years ago, and there’s a highway, I-375, in its place — a one-mile sunken expressway that has grown expensive to maintain and doesn't get as much traffic as it used to.

Now, there’s federal money to try to undo some of the damage wrought by midcentury highway projects: a billion dollars to remove highways and other infrastructure that divides, and replace them with something that better connects the community. The aim is to knit neighborhoods back together.

But figuring out what that reconnection looks like isn’t always easy.

Lawson, now 75, is also known as Mama Ravin. She grew up in the neighborhood called Black Bottom, named for its rich soil, near the river. It was a majority Black neighborhood just east of downtown, and Hastings Street was its commercial heart.

Her father worked at nearby Eastern Market, removing the bones from beef, and she would go with him to Hastings Street nearly every day.

“He could leave me at the barbershop with a sandwich and something to drink and go and take care of his business,” she recalls. “And the barber was my babysitter, or whoever he left me with. I was always safe.”

She remembers Black Bottom as a special place, where as kids they were unaware they were a racial minority. “It was vibrant and wonderful," she says.

But that vibrant community was labeled a slum and targeted for urban renewal. The city cleared a 20-block area and planned a new freeway, right on top of Hastings Street. Three hundred Black-owned businesses were destroyed without compensation.

And tens of thousands of residents — mostly Black renters — were forced to find new places to live, at a time when housing for Black families was scarce and overpriced.

Lawson’s own family was forced to move to make way for a different project, the relocation of a school. Like many Black Detroiters, displacement was something her family would experience time and again.

“My parents tried to purchase two homes and every time we would get settled in the home, we had to move because they had something coming through there,” she says. “It was just a struggle and it was kind of bad. And my dad would always explain to us, because we were asking as children, ‘Why are we always moving?’ He said, ‘I'm trying to find us a comfortable place that the government’ — this is what he would say — ‘that the government would allow us to live and thrive.’ And he just couldn't find it.”

Her parents never did buy a place of their own.

Supposedly there’s one block remaining of the street where Lawson was born, so we go looking for it. Sandwiched between the Whole Foods where she shops and a hospital where she's gone for rehabilitation, Lawson spots the sign.

“There it is right there! I’ve walked past it a million times and never really paid any attention,” she says, amazed. “It’s just this little block here ... I never knew this was still Brady Street.”

What does she think of the area now? Lawson sighs. “You know, it’s just … updated. It’s got a lot of good in it. I know everything can’t remain the same, but that 375 was just drastic.”

A city on the rebound looks forward

There's a lot that's new in Detroit these days. The city's population grew last year, for the first time since 1957. In April, Detroit hosted the largest-ever NFL Draft. And last month, Michigan Central Station staged a grand reopening following a huge renovation by Ford Motor Company, after the vast building sat empty and decaying for decades.

It’s a city trying to build the future — and one step is removing this one mile of freeway.

The city has been talking for years about filling in I-375 and replacing it with a boulevard. That effort got a big boost two years ago when the federal government awarded the Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT) $105 million for the project. U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg said sometimes fixing the roads means recognizing mistakes of the past.

“When a generation's old piece of infrastructure comes to the end of its useful life, it requires us to decide in our time whether we're just going to put things back exactly as they were … or whether we're going to build back better,” said Buttigieg, as cars zoomed behind him on the freeway.

The federal government has set aside a billion dollars for projects like these, to reconnect communities cut off from opportunity by transportation infrastructure. This effort, dubbed the I-375 Reconnecting Communities Project, looked like a slam dunk.

But almost two years later, more than 500 people signed a letter in May to the mayor and the governor, requesting the planning process come to a halt and start over.

The clock is ticking: Construction must begin by the end of next year, or the federal money could be lost.

Bryan Boyer is a member of the group behind the letter, the Rethink I-375 Coalition. He lives in Lafayette Park, the neighborhood designed by famed architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe that was built on the site where Black Bottom once had been.

For several years, Boyer has been a part of the Local Advisory Council, a group of residents and business owners who’ve been giving input. He was initially really supportive of the project, since removing the highway will generate new land and new uses.

“If we have less square footage given to roads, that means more square footage for life, for homes and shops and churches and businesses and everything else,” he says.

But Boyer thinks that the process, led by MDOT, is barreling forward without a clearly communicated conception of the end result, and without fully answering questions around restorative justice and land use. Some residents are also concerned that local businesses will suffer during construction.

“There isn't actually a vision that's on paper and agreed upon by the community and all the many, many stakeholders involved in that project as to what that city fabric is going to look like and feel like,” he says. “In my opinion, it's very hard to know if the road that you're designing and building is the right road if you don't actually know what's going to happen there.”

A transportation project that must also reckon with injustice

Michigan’s transportation department has revised its plans after community feedback, conducting a new, post-pandemic traffic study that allowed planners to reduce the number of lanes.

Jon Loree is managing the project at MDOT, and he acknowledges it's been challenging. “It’s not a typical highway project, where we’re only focused on the road,” he says.

One big reason for that is the excess property that will be created when the highway’s big footprint shrinks to a more human scale.

“It's very important what happens with that access property, especially given the history of the corridor and the urban renewal that happened” when the Black Bottom and Paradise Valley neighborhoods were destroyed, Loree says.

Among the ideas being explored for the new land is affordable housing and an incubator for minority-owned businesses. The city and the Kresge Foundation are partnering with the transportation agency on the social equity side of the project.

Leslie Love is assistant deputy director for MDOT in the Detroit metro region, and she has a vision for what the boulevard will be for the city.

“I wonder if this is the future of the Thanksgiving Day parade? Or is this the future of where people gather for all the cool stuff that we do in downtown Detroit? So it's not just Woodward [Avenue], that we now have another boulevard that has its own energy.”

She says that the agency is listening and responding to residents’ concerns.

“They want to know more about what happens with the excess land,” she says. “We're not to that portion of the program yet. We're working on it. So we’re saying, hey, come to our public meetings.”

This project is a complicated one: Remove aging infrastructure. Improve the feel of the area. Make it safe to bike and walk. And reckon with the past.

“History is history to teach us a lesson,” Love says. “We want to learn from that lesson and teach us what we need to do today. And I think we've learned some of those things and we want to get it right. This is no small thing. We want to get it right.”

Regina Lawson, who lived that history, says the highway's removal is overdue — but it still matters. And she has one request: that the new street be named Hastings Boulevard.