Section Branding

Header Content

As discrimination complaints soar, parents of disabled students wait for help

Primary Content

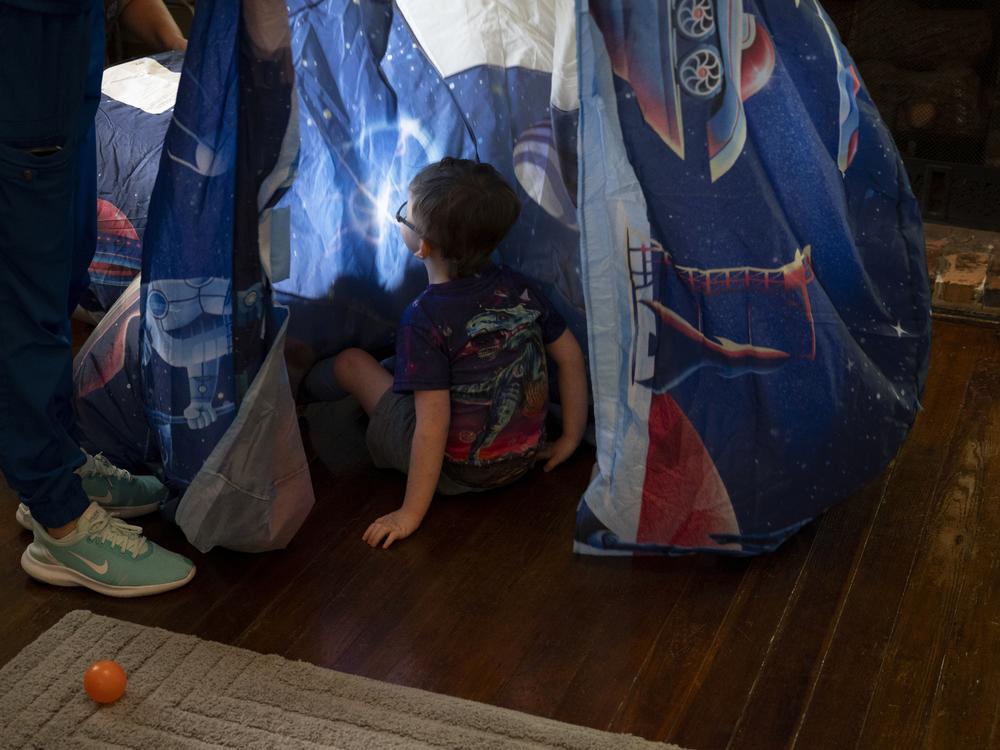

Sam is a bespectacled 6-year-old with a winning smile and a penchant for dinosaurs, as evidenced by the roaring Tyrannosaurus rex on the back of his favorite shirt.

“He loves anything big, and powerful, and scary,” says his mother, Tabitha. Sam grins mischievously as he puts his hands together in a circle — the American Sign Language word for “ball.” He’s telling Tabitha he wants to start his day in the colorful ball pit in a corner of his playroom in their home in central Georgia.

It’s a precious moment of unstructured fun in the day. Soon, he’ll have a virtual lesson with his new teacher for the deaf and hard of hearing, followed by occupational therapy, and speech and language pathology.

Sam has significant disabilities, including cri du chat syndrome, a rare genetic disorder.

He is partially deaf, so he primarily communicates using American Sign Language, or ASL, and mostly uses a wheelchair to get around.

“Sam has a complex case,” says Tabitha, who is no stranger to disability. She used to be a special education teacher, and three of Sam’s seven siblings also have disabilities.

Having that kind of experience means Tabitha knows what it takes to fight for the rights of her loved ones, including Sam. “I want him to have every avenue open to him. And what I see happening is obstacles placed and limitations set. And that is my worst fear.” That fear led Tabitha and her husband, John, in December 2022, to file a discrimination complaint with the U.S. Department of Education, saying that Sam’s school district has failed to provide him with the services the law says he’s entitled to.

They’re one of a record number of complaints – 19,201 – the department’s Office of Civil Rights, or OCR, received in the last fiscal year. These complaints involve discrimination based on race, color, national origin, age, and sex and disability.

While OCR is a last resort for many parents, the office is overwhelmed with the volume of complaints, and Sam’s case is one of thousands that is lagging in the system.

Since Sam started school, Tabitha and John have struggled to get him the services they say he needs to succeed. NPR is not using last names or naming the school district in this story to be able to freely share Sam’s health concerns.

Their complaint, like so many others, argues that Sam is not getting a “free and appropriate education,” which federal law says disabled children are entitled to. When Sam first began going to prekindergarten, Tabitha says the district did not provide a wheelchair-accessible bus, meaning Tabitha would often end up taking him herself. The building is only a few blocks from their home, but with his wheelchair and medical equipment in tow, it was difficult for Tabitha to transport Sam on her own.

And when they arrived at school, she often found the four accessible parking spaces occupied by school police or other cars. In addition to the physical barriers, Tabitha says Sam never had a dedicated special education instructor in his classroom. His previous nurse, Sherri, always accompanied him to school. “I was there in the capacity of a nurse,” she says, “but I also had to be his teacher because he didn't have a one-on-one like you should have in the classroom.”

Sometimes, Sherri and Tabitha say, there was a paraprofessional in Sam’s classroom, but not every day. And neither his teacher or the paraeducator knew ASL, making communicating with Sam a challenge.

Sherri says Sam was often left wandering aimlessly in class. “It was very frustrating watching him not be able to do all the things other kids could do,” she says. After many meetings with the school staff, Tabitha concluded they were not going to give Sam the services he needed. So, in December 2022, she made a formal complaint to OCR.

Her complaint listed several things: the lack of accessibility in parts of the school, including the parking lot and playground, the lack of special education support for Sam in the classroom, and other accessibility barriers.

Five months later, OCR opened an investigation.

A decades-long struggle over special education funding

NPR reached out to Sam’s school district for an interview, but their director of special education said she could not discuss Sam’s case due to privacy concerns. In an email, she told us that “the district takes each student’s individual needs into account when developing individual educational programs for students with disabilities. Determinations about accommodations and services are made by individualized educational planning teams made up of the student’s educators, related service providers, the family, and sometimes outside experts invited by the family or district in order to create a detailed plan to offer the student a free appropriate public education.”

School districts and states have long complained that they do not receive enough funds from the federal government to meet the needs of disabled students. When the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) was passed in 1974, it authorized federal funding for up to 40% of what it costs to provide special education services for students with disabilities .

But the federal government has never met that target. “We've been waiting 40 years now for the federal government to actually live up to its promise of fully funding the IDEA,” says John Eisenberg, executive director of the National Association for Special Education Directors.

Pandemic-related school funding helped for a while, but now that’s running out. At the same time, the number of children who qualify for special education in the U.S. is growing. “You cross-section that with the shortages of [special education] specialists and experts, and you are ripe for these issues to take place,” says Eisenberg. It’s been more than a year and a half since Tabitha filed her complaint, and the investigation into Sam’s discrimination case is still ongoing.

Since then, Tabitha has seen some improvements: the school eventually provided Sam a wheelchair-accessible bus. But then, months later, he began attending school virtually from home because of a temporary medical condition.

The school also provided an ASL interpreter for a portion of last year, but they have taken that service away for the upcoming school year, in part because Sam’s hearing loss does not meet the state of Georgia’s criteria for “deaf or hard of hearing,” meaning the district isn’t compelled to provide him instruction in ASL.

“It’s that whole theory of ‘he’s not deaf enough, I don’t know if you know how offensive that is',” says Tabitha. “I’m being told, ‘but he can hear,’ and I’m saying ‘but he can’t hear all of it.’ ”

As she awaits some resolution from OCR, Tabitha is considering a lawsuit against the district. NPR spoke with several parents of students with disabilities around the country who say their OCR cases are taking months, even years to resolve. Many, like Tabitha, are seeking outside help from advocates and lawyers to address their concerns.

“These parents are right to be concerned about how long it can take,” says Catherine Llahmon, the assistant secretary for civil rights at the Education Department. She acknowledges the frustration that parents and educators alike are experiencing in the face of rising disability discrimination complaints, which she calls “deeply, deeply concerning.”

But she says her office’s case managers are overwhelmed, each carrying 50 or more cases. Nonetheless, she says 16,448 of the 19,201 cases in the last fiscal year were resolved.

She notes that these investigations involve a long and complicated process. And while she knows that adds to parents’ frustrations, she says the department owes them “the careful evaluation of facts, careful investigation of the documentary record, talking to people at the school, as well as talking to witnesses and to families about their experience.”

Llahmon says that in the first year of the Biden administration, the OCR streamlined the online process for filing complaints to make it easier for parents. In the last fiscal year, they also added an option for “early mediation,” which allows parents and districts to agree to a single meeting with an OCR mediator to resolve their concerns rather than going through a lengthier investigation process.

“We've seen more than a 500% increase in the successful resolutions by mediation since we have had that process in place,” says Llahmon.

Tabitha and John have previously tried mediation through a state complaint, but they were dissatisfied with that process, so they opted for a full, federal investigation this time.

A glimpse of what progress looks like

As the new school year approaches, Tabitha is cautiously excited about a new development. For a few weeks, the school district has been providing Sam with instruction in ASL.

Jessica, Sam’s new teacher for the deaf and hard of hearing, is spending an hour a day, 5 days a week with Sam, via Zoom. Both she and Tabitha say they have seen his vocabulary and expression expand since the lessons started.

“It’s just magic,” says Tabitha. “This has been pulling the curtain into a dark room and seeing the light of what’s underneath Sam.”

She says she’s thrilled to watch Sam learning so many new things. “But imagine if this was every day, like it's supposed to be, and all day like it's supposed to be.”

The school district's individualized education plan for Sam next year does not include an ASL interpreter, though his hour-long lessons with Jessica will continue.

And OCR has told Tabitha that staff there are in the final stages of their investigation. In the meantime, she’s been consulting attorneys about a due process claim, but says they likely can’t afford a lawyer.

As the summer weeks roll on, Tabitha is looking ahead to the coming school year, when she hopes Sam’s health will allow him to return to a general education kindergarten classroom with the adequate special education support to learn.

She says she’ll continue fighting for Sam’s rights until he gets the quality education other children receive: “I want him to experience what every 6-year-old little boy gets to experience.”