Section Branding

Header Content

10 years after Michael Brown’s death, we went to Ferguson to ask: What’s changed?

Primary Content

Michael Brown graduated from high school eight days before a Ferguson police officer shot and killed him in the street.

The 18-year-old’s killing — 10 years ago today — put the St. Louis suburb in the national spotlight after images of people protesting in the streets, buildings burning and his dead body lying in the street for four hours were shared widely on social media and broadcast on national television.

The protests spurred the Black Lives Matter movement, born a year earlier.

The official report from the Department of Justice found no credible evidence to dispute officer Darren Wilson’s claim that Brown reached for the officer’s gun, and all the credible testimony from the day suggests that Brown was neither holding his hands up nor turning away from Wilson when he was shot.

Wilson was never charged, and many in the community and around the country maintain that justice was never served. But the events from 10 years ago still served as a catalyst for change in Ferguson — and beyond.

“What made me think it could and would change was the people in the streets in Ferguson in 2014,” Blake Strode, the executive director of ArchCity Defenders told Morning Edition.

Ferguson isn’t the same place it was 10 years ago, and many people who call it home are trying to make it better.

Systemic problems plagued the city 10 years ago. Have they been fixed?

Michael Brown’s killing led to a Department of Justice investigation of the shooting and Ferguson’s police department.

The DOJ found that the Ferguson police department was incentivized and encouraged to lobby municipal fines and fees on individuals to generate revenue for the city and that these fines disproportionately were issued to Black people in the city.

“Even relatively routine misconduct by Ferguson police officers can have significant consequences for the people whose rights are violated,” the 100-page report read.

“I think what people here have known to be true for a very long time is that the institutions like the police and surveil, arrest and target people. I think they knew that on Aug. 9, 2014, and they know that now,” said Strode of ArchCity Defenders. This legal advocacy organization was the first to raise the alarm about the fines and fees system in Ferguson.

ArchCity Defenders has seen a significant decrease in the amount of fines and fees issued to residents in Ferguson and the surrounding municipalities. In 2013, municipal court revenues in the St. Louis region were about $61 million in 2023.

Last year, that figure was $17.8 million.

“When we talk to our clients, many of them talk about the night and day experience of moving, working and traveling through their neighborhoods, their municipalities, their hometowns,” Strode told Morning Edition.

The DOJ issued a federal consent decree in 2016 to the Ferguson Police Department after its investigation, requiring the department to adhere to mandates in order to reform their police system. Those included police training for officers, more community engagement and performance evaluations for officers.

“When I got here, officers were still walking around with their heads down, because they felt like just over the years, they continue to get beat up, you know, in the public in regards to what took place in 2014,” Ferguson Chief of Police Troy Doyle told NPR’s Michel Martin in his office.

Doyle became Ferguson’s police chief last year. The city has had a string of police chiefs since former Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson shot and killed Michael Brown in 2014.

Before he was named police chief, Doyle spent 31 years in the St. Louis County Police Department. He retired from his position as Lieutenant Colonel two years after filing a racial discrimination lawsuit against another officer at the St. Louis County police department.

Doyle points to programs he’s implemented when talking about how the police department has improved. There have also been significant changes in the racial makeup of the police department: 10 years ago, there were only three Black police officers in Ferguson. Now, roughly half the police force in Ferguson is Black, he said.

Even the police uniforms have changed.

“When you see the old Ferguson police cars or uniforms and also get out of the car, trigger some people in our community, "Doyle said. “So I wanted to get totally away from that.”

Doyle is hoping that the police department will be completely compliant with the federal consent decree in the next two years.

“When you're in the position I am as a chief of police, I am the final decision here at this police department,” Doyle said. “So that's where my optimism comes from, because I can set the tone in the practices that would take place here at this police department.”

But activists like Strode think that no matter how much police reform is done, there are systemic problems in St. Louis that prevent meaningful change. One of the biggest issues is that the county is composed of small municipalities, some of which have their own police forces, courts and standards for operating. Some municipalities contract with St. Louis County Police, while others have banded together to form the North County Police Cooperative.

“It's just a system that no one would design unless you were actually trying to profit from poor people,” Strode said.

Strode believes that consolidating the municipalities under one court system and police force would greatly reduce the amount of over policing in these areas by forcing the system to stop focusing on generating revenue. There were at least 90 municipalities in 2014, though some have dissolved or joined with other towns.

“People would live much better, freer lives if we didn't have this kind of petty policing of their activities day in and day out,” Strode said.

But Doyle thinks smaller police departments are an advantage.

“Some cities like to have a smaller police department because they feel more intimate with the officers that work there,” Doyle said.

How a burned down QuikTrip shows change in Ferguson

The day after QuikTrip, a gas station less than a mile away from where Michael Brown was killed, burned down, Michael McMillan, the president of the Urban League in St. Louis called Michael Johnson, the only Black person on the board of directors at QuikTrip.

“I said, Michael, you can't just let this be vacant, abandoned, derelict. This is going to be an eyesore and it's going to be a source of decay,” McMillan said.

McMillan recalls talking to Johnson every day about what could be done with the empty lot. QuikTrip didn’t plan to rebuild the gas station, so it decided to donate the space to the Urban League and Salvation Army, who were interested in opening a community center. It was the first time ever the Urban League, which is over 100 years old, had ever taken on owning and building a center.

“It pushed me and the team at the Urban League to do things that we had never done before because they needed to be done,” McMillan said.

The Urban League’s headquarters are in East St. Louis, closer to the heart of the city. McMillan says that the Urban League never thought a lot about poverty in the suburbs of the city until the death of Michael Brown, which brought attention to the high amounts of poverty in suburban areas near the edges of cities like St. Louis.

“If you look at the inner city, there's a huge amount of non-profit social service agencies," McMillan said. “And people didn't really think that you needed to expand that much into north county.”

NPR met McMillan in his office at the Ferguson Community Empowerment Center, which opened in 2017 on the site of the QuikTrip that burned. The center is a multipurpose facility that serves as the headquarters for things like workforce programs for Black men, emergency assistance services and after school programs for kids.

“The center is for opportunity and new beginnings,” said LaKeysha Fields, the St. Louis Regional Social Services Director for the Salvation Army.

And it’s not the only new nonprofit in the area: there’s also a senior living center where an AutoZone once stood, and a Boys and Girls Club less than a mile away from where Michael Brown was shot. The Urban League also broke ground on another project recently: it plans to turn two vacant lots into a plaza, anchored by a bank and a small convention center.

Still, many lots sit vacant, as do abandoned apartments and boarded up buildings all throughout West Florissant Avenue, one of the city's main thoroughfares.

“I'm very hopeful that we can kind of plateau and rebuild and bring more businesses, institutions, you know, commercial activity on this major corridor,” McMillan said. “And then as a result, maybe people see the revitalization and want to rent in some of these apartment complexes and buy homes.”

None of these new organizations had a large presence in the Ferguson area before 2014, but now they are some of the first things people see when they drive down West Florissant Avenue.

“I don't know that this building being here would have prevented what happened. Hopefully there would have been some buffer, less likelihood,” Fields said.

What’s left to be done beyond Ferguson

NPR spoke to some Ferguson residents and asked how they feel their city has changed.

Henry Jones, Ollie Brown and Willy Powell, whom NPR met at a city park, all said they feel like things have especially improved in Ferguson’s police department.

While they might feel safer than they did a decade ago, all three of them agreed that there was more to be done, specifically for kids in the area who can often be victims and perpetrators of violence.

“We’re watching them and they are like a train out of control,” Brown said.

But they don’t think that’s a change that can happen with more policing.

“Police can’t control them,” Powell said. “It starts in the home.”

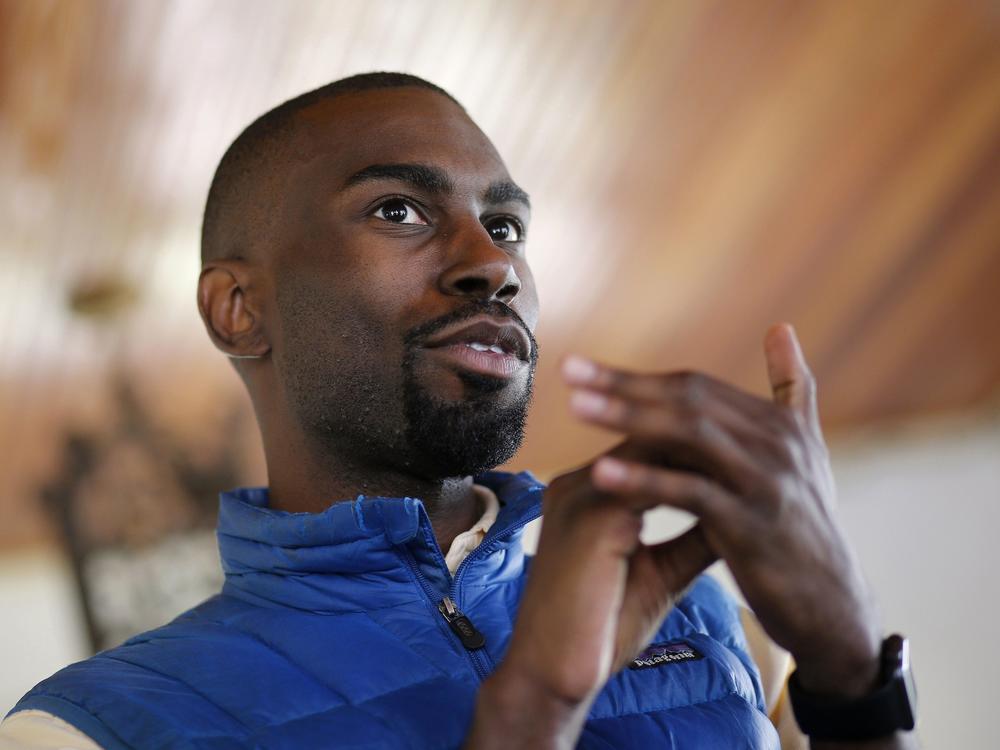

The point that reform goes beyond policing is what activist DeRay Mckesson, who became a well-known figure after the Ferguson protests in 2014, has argued for years. Mckesson now runs Campaign Zero, a social justice organization that works to reduce the power and reliance on police.

The group, he said, is working to highlight and change laws that can lead to more encounters with law enforcement and to reduce ways that formerly incarcerated people can get tangled up with the legal system again.

He pushes back against the notion that some reform hasn’t happened.

“I do think there's a weird thing that happened where there are people who want this narrative that nothing has changed,” Mckesson said.

He points to the attempt to pass the George Floyd Policing Act in Congress, new state laws prohibiting police from executing no-knock raids in Pennsylvania and new requirements for police departments to hand over data as signs of progress in police reform.

Though national scale reform for the nearly 18,000 police departments in the United States hasn’t happened, McKesson doesn’t feel like solutions to issues in policing can come from the federal government.

“I think that people have been looking for something like a national silver bullet as opposed to understanding that the best version of the change will be a 50-state strategy,” McKesson said.

Correction:

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that each municipality in the St. Louis area had its own police force. It has been updated to reflect that not all do and that some contract with St. Louis County Police and that others have formed a law enforcement body. It has also been corrected to reflect that there were at least 90 municipalities in St. Louis County and some have dissolved.