Section Branding

Header Content

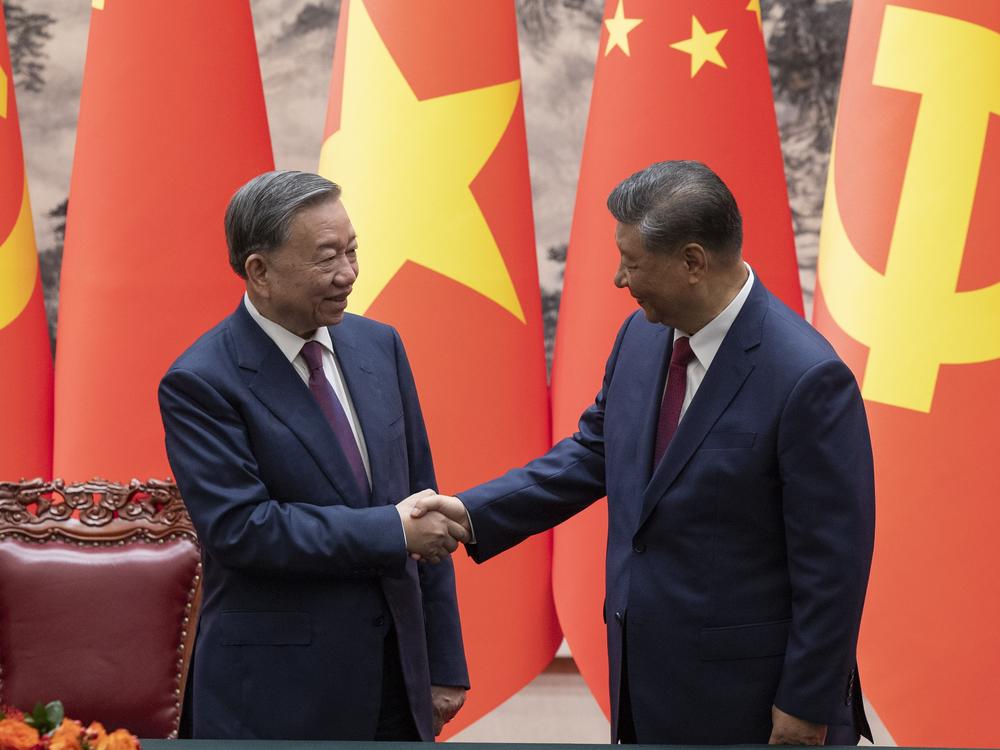

'No stone unturned': Vietnam's new party boss extends his anti-corruption campaign

Primary Content

General Tô Lâm’s ascendancy to the top position in Vietnamese politics has ended months-long political turmoil and infighting but not the feared anti-corruption campaign started by his predecessor, the late Nguyễn Phú Trọng. It will likely continue as the new leader tries to make good on his pledge to stamp out corruption, even if the economy suffers, at least in the short term.

The new party secretary, the 67-year-old Lam will hold the post of state president, as well, at least until the next Communist Party’s Congress in early 2026 and will also continue to use the anti-corruption campaign to consolidate his power.

His pragmatic approach to ideology and diplomacy may see Vietnam become more confident in pursuing its national interests while navigating the pitfalls of the U.S.-China rivalry. But the anti-corruption campaign is paramount. Though there are pitfalls.

Relentless anti-corruption

Lâm's pledge to leave “no stone unturned” to fight corruption leaves the executive branch of Vietnamese state further weakened because of mass dismissals and expulsion of senior ministers.

In the first day of Lâm's leadership as the secretary general of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV), an investigation into high-level allegations of "Party rules’ violations" — a euphemism for corruption — brought down a deputy PM, a young minister and two provincial Party chiefs.

All four were removed from the CPV Central Committee on Aug. 3, the same day that Lâm revealed his policy in a keynote speech to the Party, in which he pledged to carry on the anti-corruption drive. He helped implement that drive as security minister under the late Nguyễn Phú Trọng.

How long will the purge last?

The latest dismissal of Deputy Prime Minister Lê Minh Khái, however, has raised eyebrows in the business community, both in Vietnam and abroad. The deputy PM was in charge of a large portfolio, including macroeconomic policies, the state budget, the banking system and the stock exchange. Khai had represented Vietnam at an international conference in Tokyo in June and met with Jared Bernstein, the chairperson of the United States Council of Economic Advisers in Washington, D.C., in the same month. Khai's removal from the Central Committee put further pressure on the government of Vietnam's prime minister, Phạm Minh Chính.

Since 2023, Chính has already lost two deputies (Phạm Bình Minh and Vũ Đức Đam), and numerous ministers. This has led to speculation from Vietnamese observers who wondered whether the government was not able to function properly because of corruption — all the dismissed politicians were publicly accused of being involved in some shady deals with the businesses — or if decision making has been paralyzed by the anti-corruption drive, with some bureaucrats wary of making decisions and falling afoul of the anti-corruption authorities.

But Lâm is steadfast in his desire to carry out the campaign, because the “blazing furnace will feature prominently in his process of consolidating power,” wrote Vietnam watcher Alexander Vuving, professor at the Asia Pacific Centre for Security Studies, Hawaii, USA on X.

Moreover, as Lâm has acknowledged, anti-corruption also brings recognition and approval from the public and the international community. That makes it a source of newly found legitimacy for himself and his subordinates, mainly young police generals recently promoted to senior positions in the Party. They will be very busy in the coming months because there are still many large-scale corruption cases still under investigation.

There are commentators who say Lâm's supposed “pragmatic authoritarianism” is good for Vietnam’s economic growth. But in the short term, the purge of key figures in charge of economic policies in the government under Nguyễn Phú Trọng has, as noted, already made Vietnamese businesspeople and foreign investors concerned. To address that, Lâm has signaled that he wants to be a new type of leader who uses the ‘rule by law’ principle to run the country.

One of the first works Lâm has embarked on so far as Party leader was to chair the meeting of the Judiciary Committee of the Party to launch a legal reform for Vietnam’s courts, public prosecutor’s office and the law enforcement branch. In his vision, such a reform will take shape this year and run until 2030 to redefine “the tasks between three branches of power: the legislature, the judiciary and the executive.”

While it’s not a separation of powers in a Western democratic sense, the reform, if implemented properly, may create a semblance of checks and balances within the context of Vietnam’s Leninist system. Any internal reforms, however, won’t make a change to the human rights situation, given the Ministry of Public Security has been granted more authority under the new Basic Security Law in July this year. This month, activist Nguyễn Chí Tuyến, one of 269 people arrested in recent years, is scheduled to go on trial on anti-state charges, reported Human Rights Watch.

Lâm’s energetic agenda also touches on the eternal question of Vietnam’s socialist path. This elephant in the room has been there for more than three decades, since the Reform era began in the late 1980s. The recent decision by the U.S. Commerce Department to reject Vietnam's bid to change its non-market economy status after a year-long review came as a blow to Hanoi’s reformist credentials, revealing a painful truth that Vietnam cannot be both a socialist-oriented market economy where the state dictates and intervenes, and a market economy at the same time.

In a recent article published by Vietnamese state media,

It’s also worth noting that in reference to the regime’s official history, Lâm has removed the traditional rhetoric about “the heroic anti-American resistance,” leaving only a sentence about “the Vietnamese victory over the French colonialist war of aggression.” Together with his decision to send a Vietnamese coast guard ship to join the Philippine navy in holding firefighting and search-and-rescue exercises off the coast of Manila earlier this month, it’s clear that Vietnam under To Lam’s leadership is confident it can safeguard its strategic autonomy — which in practical terms means a closer relationship with the U.S. and its allies to balance China’s growing power in the region, while maintaining close ties with Vietnam’s northern neighbor.

Lâm this week made a visit to Beijing his first state visit abroad, a nod to the importance that both Vietnam and China see in their bilateral relations, The Associated Press reported. Lâm is also expected to attend the annual United Nations General Assembly in September, after which he’s expected to meet with U.S. President Biden.

Giang Nguyen is a visiting senior fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore. He was the former BBC Vietnamese editor in London.