Section Branding

Header Content

This is genius: A new graphic novel imagines conversations between Einstein and Kafka

Primary Content

It’s April 1, 1911, and 32-year-old Albert Einstein — former bureaucrat at the Swiss Patent Office, with a half-decade old doctorate in physics from the University of Zurich — sits in a train car with his two sons and his wife, fellow physicist and mathematician Mileva Marić. They are travelling from Zurich to Prague, where Einstein has landed a job as a full professor in theoretical physics, teaching in the German section of what is now Charles University. He has a few things on his mind, including money troubles, but most critical is his unfinished theory of relativity. When they leave the city 15 months later, Einstein will have cracked the code.

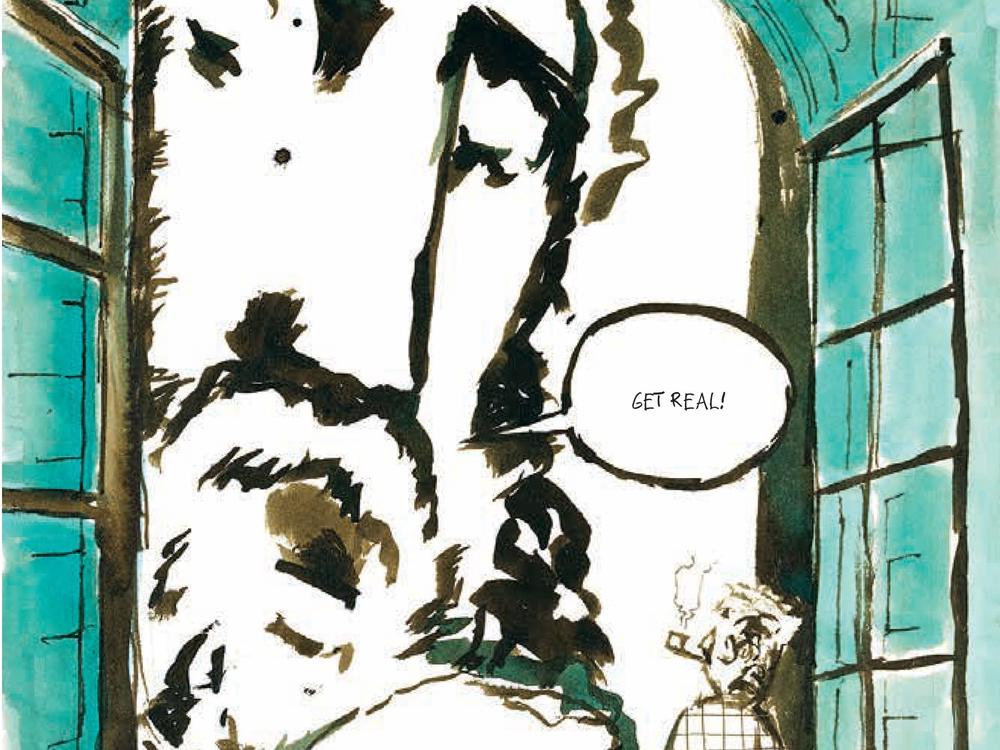

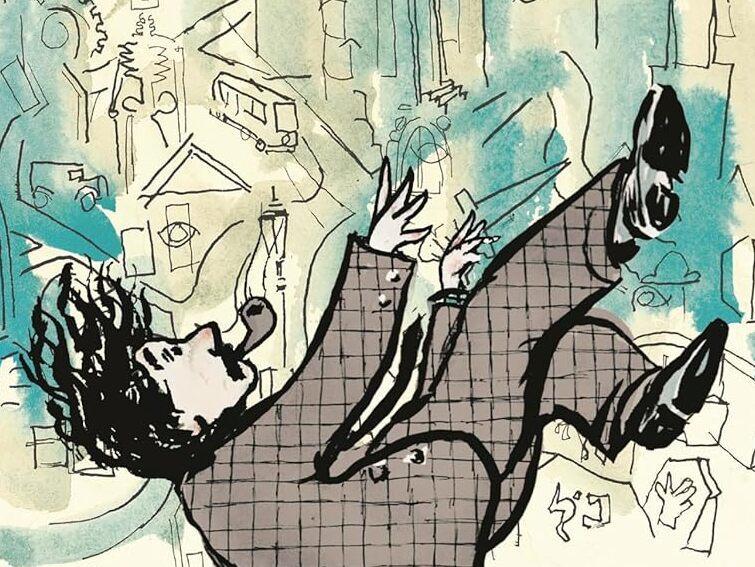

What happens over the course of this long, mysterious year in Prague is the question driving Ken Krimstein’s new graphic novel Einstein in Kafkaland. Part biography, part historical fiction, Krimstein playfully explores the possibilities, building, with footnotes, on a thorough archive of letters, diaries, and other research. The result, a thought-provoking work made up of comics suffused in a gentle mix of aquamarine watercolors, is equal parts joyful and ruminative. (Think: Alice in Wonderland meets The Lives of the Poets meets Krazy Kat.) The full subtitle to the book — How Albert Fell Down the Rabbit Hole and Came Up with the Universe — signals the lavish whimsy that goes a long way towards making this such a delightful, inspiring read.

Throughout, cartoon-Einstein sports his characteristic pipe alongside a signature frizzy head of hair. But it’s his obsessive ruminations that perhaps most effectively signal what has become Einstein-the-character, a culmination of all the gossip, public appearances, private words, and first-hand accounts of one of the best-known scientists to have ever lived. Krimstein pairs Einstein’s story with that of Franz Kafka, who was 28, virtually unpublished, and living with his parents in a house in Prague when Einstein arrived for his short but impactful stay. What binds the two together, in addition to an alleged one-time meeting at a weekly salon, is a complementary preoccupation with getting at the truth — “the true truth” — against all odds, and against many other people’s better judgements. For both, a journey to find this truth, whether in science or literature, is one that will sometimes alienate as painfully as it may ultimately bind them to others.

During Einstein’s time in Prague, a time in which he works out his theory of relativity, Kafka will have his own breakthrough. In one long feverish night he will pen the short story, most often known in English as “The Judgment,” which will launch an unparalleled writing career forever transforming art and literature. Like Einstein’s completed theory of relativity, Kafka, too, will offer the world a new way of thinking. It’s a way of thinking that, our narrator assures us, “we’re all still struggling to catch up to.”

Despite his title, Krimstein centers his book unevenly, focusing mainly on Einstein, and taking us step by step through the meditations that lead to his discovery. Nonetheless, along the way he also provides readers with glimpses into the life of the perpetually melancholic insomniac insurance clerk, Kafka. We witness, for example, an early morning swimming routine with his best bud — and future literary executor — Max Brod. But what Kafka’s presence in the narrative most crucially enables are imagined conversations between him and Einstein. In these, the two puzzle, and sometimes commiserate, over what it means to see the world differently from everyone else. What happens when you believe so confidently in your own hard-won perceptions that you risk killing the heroes that brought you there?

Krimstein, a well-published cartoonist whose previous work includes another delightful graphic biography, The Three Escapes of Hannah Arendt, luxuriates in intellectual history shoulder to shoulder with juicy biographical details. He depicts Einstein debating with his foe, Max Abraham; taking fantastical trips into a four-dimensional world with Euclid; and walking and talking with Austrian physicist, and dear friend, Paul Ehrenfest. And he exposes, too, scenes of the future Nobel Prize winner in the bath, trying to kill off bedbugs; or engaging with his young children, and wife, in Gedankenexperiments (thought experiments), to help him think through the problems that continually occupy him.

At its heart, Einstein in Kafkaland is the story of ordinary genius. It unwraps the ways in which genius so often arises out of ordinary circumstances. Perhaps even more compellingly, the book tracks how unimaginable discoveries develop following exchanges with others — friends and family, colleagues and nemeses, neighbors and role models. Aberrations aside, works of genius most wholly emerge in dialogue.

Tahneer Oksman is a writer, teacher, and scholar specializing in memoir as well as graphic novels and comics. She lives in Brooklyn, N.Y.