Section Branding

Header Content

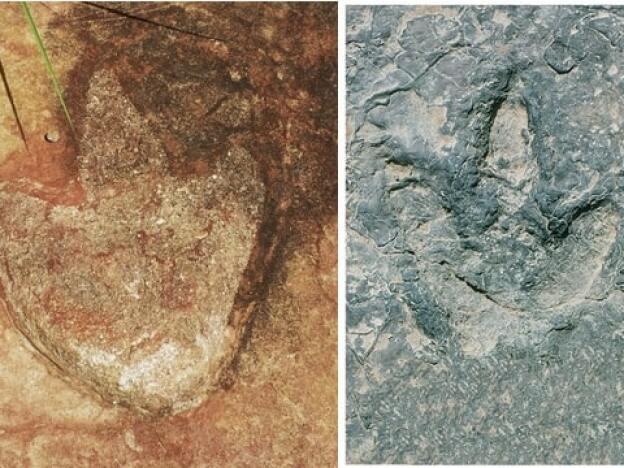

Matching dinosaur prints were found an ocean apart in Africa and South America

Primary Content

Tens of millions of years ago, South America and Africa were part of the same land mass, an ancient supercontinent called Gondwana.

At some point, the two continents we now know started to pull away from each other until there was just a thin strip of land at the top holding them together.

A group of scientists say in new research that matching dinosaur tracks found in modern-day Brazil and Cameroon were made 120 million years ago along that narrow passage before the continents separated.

“There was just a neck of land connecting the two, and that neck of land is the corridor that we’re talking about,” said Louis Jacobs, a professor emeritus of earth sciences at Southern Methodist University.

Jacobs led a team of international scientists who analyzed more than 260 tracks made by Early Cretaceous dinosaurs, mostly carnivorous three-toed theropods and also probably some sauropods or ornithischians.

They found that the prehistoric tracks in both countries were strikingly similar, despite being 3,700 miles apart.

Imprinted in the sediment along ancient rivers and lakes, the dinosaur footprints were roughly the same age and shape and shared certain geological features. The scientists found signs in both the Borborema region of Brazil and the Koum Basin in Cameroon of the major geological events that led to the two continents splitting apart.

Evidence suggests that the ancient area connecting the two continents contained rivers and lakes, which could have formed the basis for an ecosystem containing plants as well as herbivores and carnivores, the researchers say.

Jacobs says it’s not necessarily surprising to note that South America and Africa once fit together like puzzle pieces and that animals must have roamed across that invisible boundary throughout history.

“But what is surprising is when you can actually narrow down a time and a place towards the end of the connection between the two continents and say this is the way the dinosaurs were able to move,” he said.

The study was published by New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science.

The dinosaur tracks in Cameroon were first identified in the 1980s. But Jacobs and the other researchers recently gave them another look after the death of a colleague, the late paleontologist Martin Lockley, using scientific techniques that weren’t available at the time.

“I had not thought about dinosaur tracks in Cameroon for decades, and then just going back to them and starting to look at them and asking them what they’re trying to tell us, it was such a surprise to see how much had been learned in those decades and how much the story improved,” Jacobs said.

“I think that’s part of the adventure of — not just paleontology — but all science.”