Section Branding

Header Content

Russian publishers in exile release books the Kremlin would ban

Primary Content

In Vladimir Putin’s Russia, writing about certain subjects — the war in Ukraine, the Russian Orthodox Church or LGBTQ+ life — can mean prison time. But for a new generation of Russian writers living in exile, efforts to resist censorship are alive and well.

Taking inspiration from Soviet dissidents, publishers are finding innovative ways to bypass Russia’s draconian restrictions.

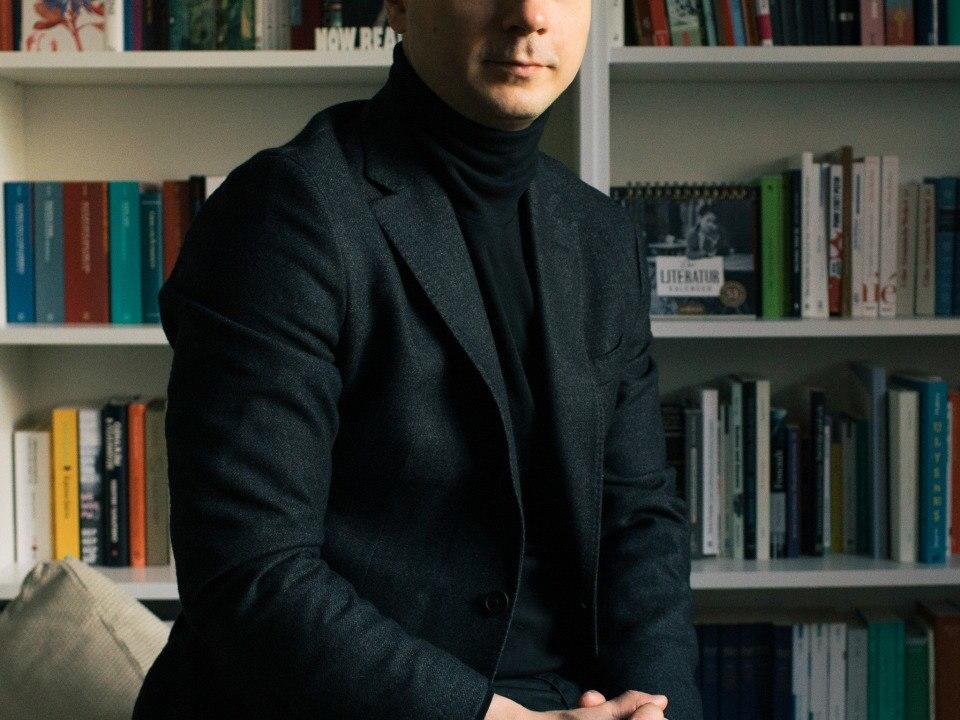

In the Soviet times, passing around banned books was dangerous because police could easily trace them. Now, with digital files, they can be shared without a trace, if done smartly, explains 35-year-old Felix Sandalov, who now lives in exile in Berlin.

Sandalov leads the StraightForward Foundation, which acts like a pro bono literary agency. It connects Russian authors, writing about sensitive topics, to publishers abroad, who publish their work in different languages. The foundation only requires that the authors agree to post the Russian versions of their manuscripts online for free for readers back home.

The goal is simple but ambitious: to document the harsh realities of modern Russia, from the war in Ukraine to political persecution, and make these works accessible to the Russian people.

"There’s an urge to document it," Sandalov said in an interview, reflecting on the "catastrophes and war crimes" that have unfolded under Putin’s government.

Sandalov’s strategy recalls practices known as samizdat from the Soviet era, when dissidents circulated typewritten copies of banned manuscripts like The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov or Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago.

In today’s digital age, the risks are different.

Their first major release, a book about Russia’s mercenary Wagner Group, has reached more than 30,000 readers in just a few weeks, thanks to the digital distribution of free PDFs online. In a nation where independent journalism has been stifled and government propaganda reigns, these books offer a rare, uncensored view of current events.

Another recent release explores the story of Memorial, the Nobel Peace Prize-winning human rights organization. Memorial, once a key voice in documenting Soviet-era crimes, was forcibly shut down by the Russian government at the end of 2021. Author Sergey Bondarenko worked for Memorial, but “is nevertheless able to look at it through a kind of critical lens, said Aleksandr Gorbachev, the editor-in-chief of the StraightForward Foundation. He said Bondarenko is trying to understand what went wrong and why Memorial and other rights groups were not able to prevent “the authoritarianism that rules the country.”

Other books in the works include a family history of a woman from Chechnya, including her perspective of Putin’s crackdown on the region, an examination of the Russian Orthodox Church and its ties to the Kremlin, and a book jointly written by Ukrainian and Russian journalists about the kidnapping of Ukrainian children by Russia.

Popular authors in Russia, who have spoken out against Russia’s war in Ukraine, have seen their books taken off the shelves. In Russia, it is forbidden to even describe the “special military operation” in Ukraine as a war or to discredit the armed forces.

The StraightFoward Foundation’s Alexey Dokuchaev had to sell off his two publishing houses, Individuum and Popcorn Books, after a backlash over a widely popular young adult novel, Summer in a Pioneer Tie. It ran afoul of Russia's ban on LGBT "propaganda" and Dokuchaev was blacklisted as a "foreign agent" — a label the Kremlin often uses for people who violate its increasingly draconian censorship laws.

Now living in Belgrade, Dokuchaev said he fears he would be jailed if he returns to Russia. A life in exile was not what the 43-year-old had imagined for himself. Dokuchaev once formed a youth political party called the First Free Generation, “because we were the first generation, who were actually Soviet-free,” he said. Little did he know how things would turn out.

In exile, he's trying to help writers expose the truth about Russia, as Soviet dissidents did decades ago.