Caption

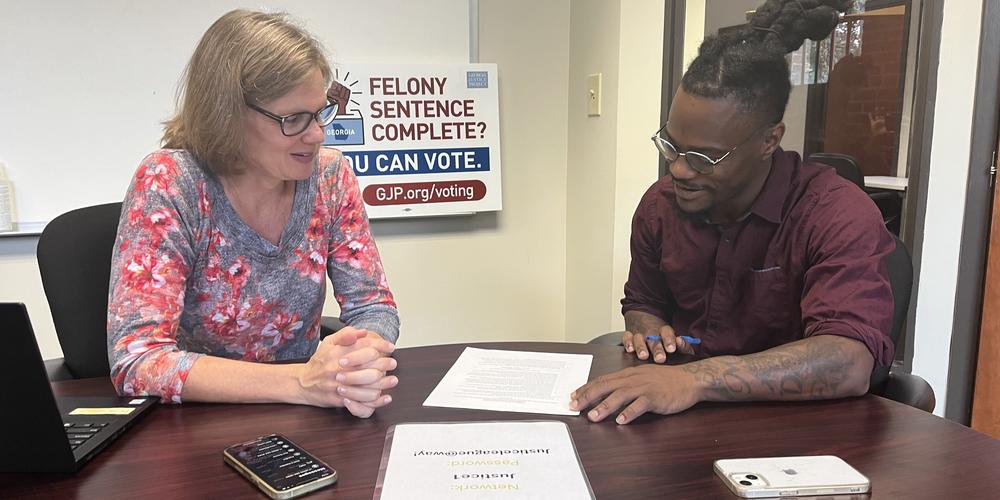

Ann Colloton and Dominique Harris work on outreach at the Georgia Justice Project to spread the word that people who have a felony conviction in their past may be eligible to vote.

Credit: Amanda Andrews / GPB News

Caption

Organizers from Atlanta and Augusta pose for a group picture before canvassing in Augusta to register voters.

Credit: Amanda Andrews / GPB News

Caption

Ikethia Daniels signs the back of another canvassers shirt asking people to vote in her honor.

Credit: Amanda Andrews / GPB News

Caption

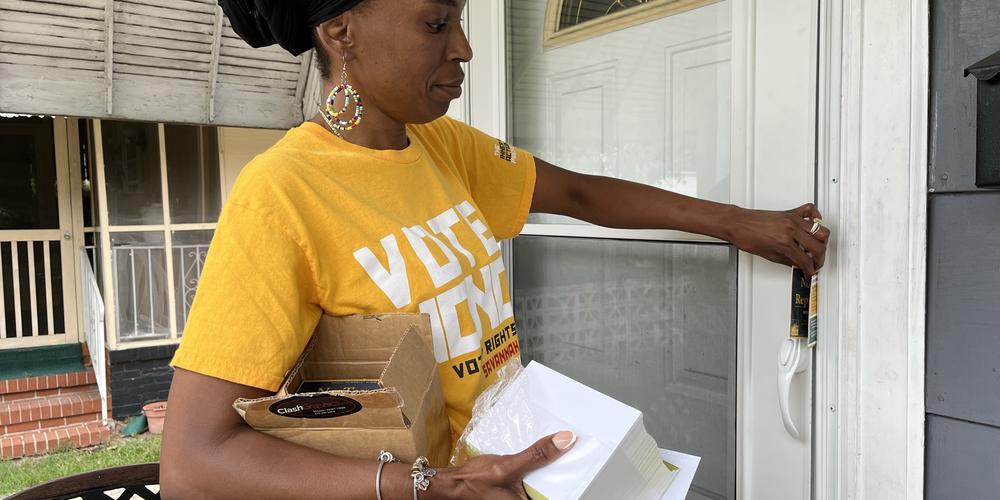

Kareemah Hanifa places a flier in the door of a house in Augusta as part of the vote in my honor canvassing effort.

Credit: Amanda Andrews / GPB News

Caption

Canvassers with IMAN Atlanta place a yard sign in front of a church in Augusta.

Credit: Amanda Andrews / GPB News