Section Branding

Header Content

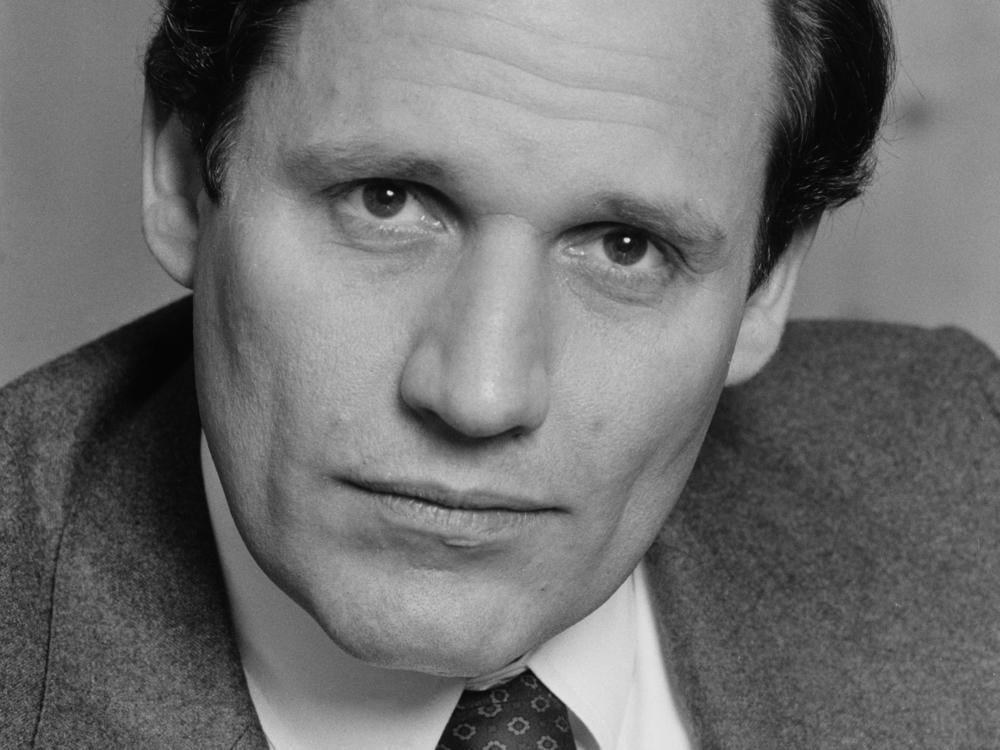

Bob Woodward takes NPR behind the headline-grabbing moments in his new book

Primary Content

Legendary journalist Bob Woodward’s new book War — like so many of his books about the American presidency over the last half century — is generating headlines.

Like the one about the COVID test machine then President Donald Trump sent Russian President Vladimir Putin in the early days of the pandemic.

Or the seven secret phone calls Trump had with Putin after he left office.

And the detail that Secretary of State Antony Blinken urged President Biden to drop out of the race after the debate in June.

But the books that Woodward writes are about a lot more than juicy nuggets that rocket around cable news and social media.

They take you into the room where it happened and into the key meetings where major decisions about war and peace are being made.

That’s especially valuable in an administration like Biden’s, which has been so careful and scripted in public appearances.

Woodward spoke to All Things Considered host Scott Detrow about the headline-grabbing moments, and recounted how key moments and meetings in recent years played out behind closed doors.

The conversation begins with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and how the U.S. was responding to the possibility of nuclear weapons being used.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Interview highlights

Scott Detrow: We knew from public statements from President Biden, from National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan and others, that there were deep concerns about the threat of nuclear weapons. But in the book, you describe detailed meetings where the Biden administration is taking this incredibly seriously. They're very concerned. How real was the threat of nuclear weapons in the fall of 2022?

Bob Woodward: Well, it becomes very vivid because of the intelligence and because of the assessment. It's 50% — a “coin flip,” as one of Biden's aides says. And the worry is so deep, “Oh my god, we're going to have nuclear use in the Biden presidency.” Which is the last thing, or one of the last things, he wants.

And so they're all over it. And being in the enemy tent, they're trying to stop it, realizing, to a certain extent, all the intelligence, all the assessments they have of Putin, that Putin is just obsessed with Ukraine, [feeling that] it belongs to Russia. And Putin writes some things publicly that it is not a borderline decision for him, it is, “This is ours. We're going to just take it.”

Detrow: And despite those pleas, threats, urging not to do this, the war begins. And at a certain point, when Russia is on its heels, like you said, the intelligence says that it's a coin flip moment of whether or not Russia is going to use nuclear weapons. Can you walk us through some of the reporting that you've gathered, of the direct phone calls from the Secretary of Defense and others to their counterparts in Russia, saying, “Don't do this.”

Woodward: Yeah. I mean, the most vivid one is Secretary of Defense [Lloyd] Austin. I have a literal transcript, if you'll permit me to read some of it, because it makes the knowledge that they have real, and how they're dealing with this crisis. And so Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, they agree in the National Security Council, let's call your counterpart, Sergei Shoigu. And first, Austin says to Shoigu:

“We know you are contemplating the use of tactical nuclear weapons in Ukraine. First, any use of nuclear weapons on any scale against anybody would be seen by the United States and the world as a world-changing event. There is no scale of nuclear weapons use that we could overlook, or that the world could overlook.”

In other words, he is not just saying, “Hey, what's going on?” It's, “We know.” And there's a kind of analytical sophistication here, you kind of wonder what really happens in these calls. And so here it goes on and says: “If you did this, all the restraints that we have been operating under in Ukraine would be reconsidered,” Austin said. And, “This would isolate Russia on the world stage to a degree you Russians cannot fully appreciate.” Shoigu says: “I don't like, kindly, to being threatened.” Austin says, I think in one of the bluntest, open interchanges I've ever learned the details of at this high level: “Mr. Minister,” Austin said, “I am the leader of the most powerful military in the history of the world. I don't make threats.”

Detrow: As you said, you've been covering national security for a while now. You've been covering administrations from the Nixon administration on. Was this the most serious nuclear threat that you've reported on?

Woodward: Yes. Because they're talking about it and in dealing with Ukraine. And the way Putin looks at this in the doctrine of, “We can't have a catastrophic battlefield loss.” And it lays it out in the book, and there are private calls between the generals on this, in that situation, we are dancing in history, in a way, and they know it.

Detrow: What was Vice President Harris' role in all of these big national security conversations, these key moments that we're talking about: the beginning of the Ukraine war, the Russian nuclear threat, the early days of the Israel Hamas war?

Woodward: She's going to president school. That's what vice presidents do. And as best I can tell, she's at almost all of the meetings, she gets involved. And at one point they're trying to actually respond — and within the National Security Council [NSC] they're discussing — what to do when Israel has really kind of pushed back Iran. I mean, not kind of, but really eliminated the strike of massive numbers of ballistic missiles. And they're in the NSC and Biden — I think [Harris] is remote on a screen — says, you know, “What should we do?” And she's the one who says, “Take the win.” And Biden goes through his response and literally says “take the win” to Netanyahu, that's his theme. Stop the momentum of this catastrophe.

Detrow: And that did lead to a slight cooling of the ramping up of tension between Israel and Iran, at least in that particular moment after that first wave of airstrikes on Israel.

Woodward: Yeah, exactly. But everything is a particular moment, and that's why it is nice to be able to work on the long form in a book, and you can see the steps, and in many, many cases, the exact language.

Detrow: I do want to ask, with Ukraine specifically, there are so many moments that you document where it could have gone either way. It could have expanded into a much more serious confrontation that drew in other countries. There could have been a nuclear exchange. Any sense from the conversations you were having, from the interviews you were doing, how the Ukraine war would have played out differently had Donald Trump been in the White House?

Woodward: I quote Jake Sullivan, the national security adviser for Biden, saying that if Trump had been president, Putin would be in Kyiv now. Why? Because Trump, who loves dictators and the unity of power in one person, would have waved Putin right into Kyiv. There would have been no pushback. Why? And this is what Jake Sullivan says, which has a lot of truth, “Trump loves dictators.”

Detrow: In an epilogue, you kind of give your conclusion to all of it. I've read just about all of your books, and I didn't remember you weighing in in that way before.

Woodward: No, that's quite correct. But this was so clear. And I definitely am getting older, and as I go around and people say, “What do you think? What's your conclusion?” you know, the reportorial curtain comes down, “Oh, I'm just a reporter. I'm just a reporter.” I think in this case, because I was able to get enough detail about the sequences that it was almost an obligation to tell people, yeah, this is what I think.

Detrow: Washington politics has changed so much since you started writing about presidents. Has that changed the way that you report these books?

Woodward: No. I mean, the way to report the book is to report the book. And keep calling people, keep doing it, keep going back, keep trying to make sure you give people an opportunity to state their experience, and get notes and documents and take readers as close as possible to not just the language but the emotions that are emitted in these debates.

Detrow: Do you think it's changed the way people read these books, or changed the effect of the books on the political scene?

Woodward: It's a big question. I don't know.

Detrow: Because we just seem to be in a world where very few new revelations seem to affect the political consensus.

Woodward: No, I think they do. I mean, in this book is the information that was not known about Trump sending the COVID testing machines — not just the tests, but the machines — to Putin. And the discussion he has with Putin about this, and Putin says, you know, “Don't tell anyone.” And Trump [saying], “Oh, I don't care.” And Putin says, “No, don't tell anyone.” Because he's looking out — this is an alliance. And of course, what did they do? Cover it up.

I noticed Vice President Harris picked up on this, and you could just see her emotions about here we are in this epidemic, and the president of the United States is taking expensive, coveted testing machines and sending them to Putin and Russians, and then they cover it up. As is always said, the cover-up is often worse than the crime. And it's a political point Harris is trying to make, but I saw there was a kind of emotional connection that she was displaying.

Detrow: I want to end by going back to an interview you did with my colleague, Mary Louise Kelly, when your book Rage came out in 2020. You seem to indicate at that time that sometimes you question why you kept getting drawn back into doing another one of these books and keep going at it. And I'm curious how you're thinking about that now. Are you already thinking there's a new president coming in in a few months, I better get back to work? Or how you're thinking about that question?

Woodward: I'm thinking I need to get back to work.