Section Branding

Header Content

Why was a Kentucky judge killed? So far, it remains a mystery

Primary Content

WHITESBURG, Kentucky – Since the local sheriff here allegedly gunned down the district judge last month, the people of Letcher County remain unsettled and perplexed by this one-of-a-kind killing.

In late September, prosecutors say, Sheriff Mickey Stines drew his gun on Judge Kevin Mullins, his longtime co-worker and friend. Video from inside the judge’s chambers appear to show Stines repeatedly firing on Mullins, who tries to shield himself behind his desk.

After the sheriff left the judge’s chambers, local attorney Tyler Ward recalls seeing Stines standing on Main Street as police in tactical gear rushed into the courthouse, searching for what they thought was an active shooter.

“The entire time, he [the sheriff] never unholstered his sidearm whatsoever, which I thought was odd,” says Ward, who noted that the sheriff seemed strangely calm under the circumstances.

Police arrested Stines minutes after the shooting. He was charged with first-degree murder. As police took him into custody, Stines reportedly made a cryptic statement that authorities are still trying to decipher.

“They are trying to kidnap my wife and kid,” Stines said, according to testimony from Kentucky State Police Det. Clayton Stamper, who is leading the investigation.

The sheriff, who officially “retired” after the shooting and has since been replaced, has pleaded not guilty.

Killings have long been part of the landscape of southeastern Kentucky, which has historically had a high homicide rate. This is a rugged region of steep mountains where the economy was built on coal. Many people here own guns. Personal and family disputes can turn deadly.

But Mullins’ killing has reverberated more than most.

One reason is precedent. A law enforcement officer killing a judge is almost unheard of anywhere in the United States in modern times.

“This is definitely a unique case,” says David Carter, a professor at the Michigan State University School of Criminal Justice.

The nearest, modern equivalents occurred in 1988. That’s when a judge in Grand Rapids, Mich., was killed by her estranged husband, a veteran police officer. The same year, a retired New York City police officer shot and killed a judge in Westchester County, after the judge dismissed a suit filed by the officer’s daughter.

Judge Mullins’ killing has also jolted Letcher because both men had served in the courthouse for more than a decade and so many people knew them. When candidates run for office in this county of about 21,000, they have to campaign in the hills and hollers, where they shake a lot of hands.

“You might not know every person in the county, but you're going to know close relatives of every person in the county,” says Wes Addington, a mine safety attorney, who runs the Appalachian Citizens' Law Center in the county seat of Whitesburg, which is about a two-and-a-half hour drive from Lexington.

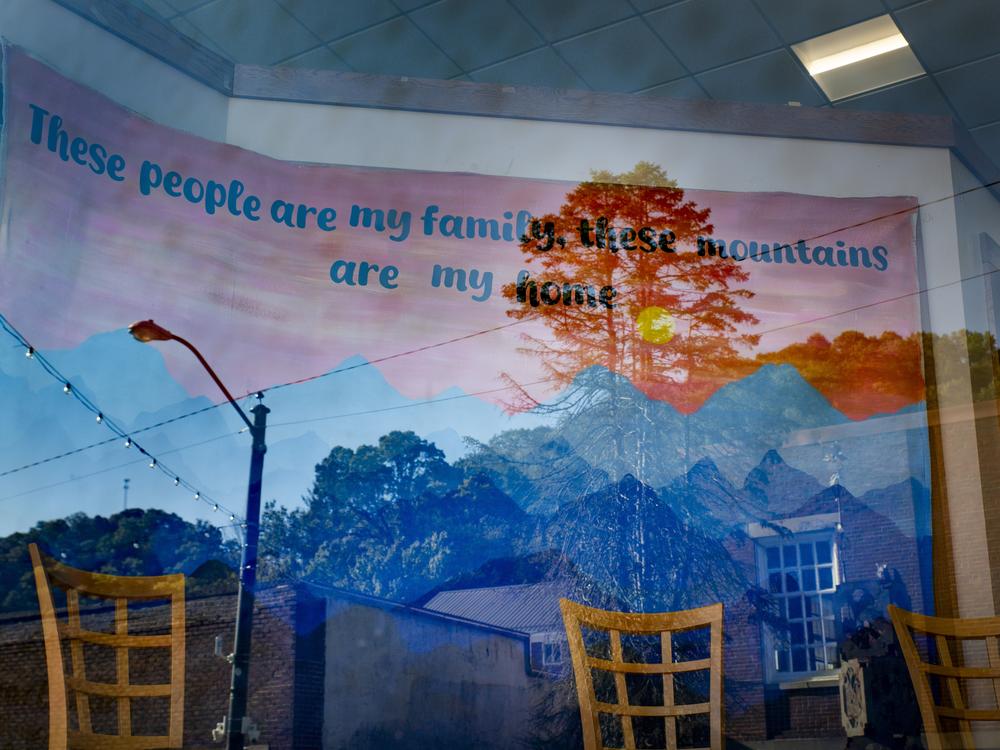

This part of Kentucky is not an easy place to live; many leave for better opportunities. But people often stay because of family ties, and there is a culture of looking after one another when floods and other hardships arrive.

“That sense of community makes a tragedy like this one that much more difficult and that's because so many people are connected to it,” says Addington. “The lasting effects are going to be probably measured in decades and not years.”

Another thing that makes this killing difficult for people is that Stines, 43, and Mullins, 54, knew each other well. Before becoming sheriff, Stines served as Mullins’ bailiff. Hours before the shooting, Ward, the local attorney, says he saw the two of them having lunch with others just down from the courthouse at the StreetSide Grill & Bar, where a cheeseburger costs about $9.

And, of course, both men were entrusted to enforce the law here. Ward says if someone like the sheriff allegedly takes justice into his own hands, what’s to stop others from doing the same?

“This cuts to the heart of an ordered society, a democracy,” he says of the violence. “People feel like we're standing on quicksand.”

As people try to divine a motive for the killing, some are focusing on Stines’ state of mind. Prosecutors have obtained a deposition he gave three days before the shooting.

A lawsuit in federal court claims the sheriff knew or should’ve known one of his own deputies had coerced a drug defendant to have sex in 2021. The defendant said the deputy asked for sex in exchange for removing her ankle monitor. She said the rape occurred after hours in Mullins’ chambers, the same chambers where the judge was killed.

The judge and sheriff denied any knowledge of the crimes to which the now-former deputy pleaded guilty. It’s unclear if the case is connected to the shooting.

The plaintiff and her two attorneys said Stines appeared agitated during the hours-long deposition and frequently asked for breaks. At one point, Stines was asked whether he had authorized his deputy to use public equipment to manage the ankle monitors.

“I don’t recall,” said Stines. “ I am having an episode. Sorry.”

Stines took another break, one of 10, according to the deposition.

The following day, Stines, who usually returned press calls promptly, took many hours to get back to a reporter about a fatal accident, according to The Mountain Eagle, Letcher’s weekly newspaper. Editor Ben Gish said Stines told his employees not to answer any questions about anything while he was away from the office. Gish said this was out of character for Stines, who was normally friendly to the press.

“I just thought that something had to be bad wrong if the sheriff’s office wasn’t releasing information that was that simple,” Gish said.

The lack of an official motive has left a vacuum that Gish says some people here have filled with rumors. The day after the killing, he made a couple of stops on his way out of town.

“Everywhere I went, people had the wrong information and they had picked it up from social media — and the most vile accusations ever,” said Gish, whose newspaper office is just down the street from the courthouse.

Some people in the county have tried to quiet speculation, including Michael Clark, a local preacher, who said he was good friends with the sheriff and the judge.

“You know, you just really need to be praying and quit gossiping and spreading rumors because you are going to be really surprised when absolutely nothing you say or post is true or accurate,” Clark said in a video he posted on Facebook.

Clark soon came under attack from people who questioned his credibility, and he took down his video.

Police say Stines and Mullins met in the judge’s chambers midafternoon on Sept. 19 and had an argument. Stines called his daughter and then dialed her number on the judge’s phone.

Kentucky State Trooper Matt Gayheart said, despite earlier police testimony suggesting otherwise, there was no evidence the daughter’s number had been previously called from the judge’s phone.

State police are examining the cell phones. A grand jury will now consider the case.

Jeremy Bartley, Stines’ attorney said on the cable channel Law & Crime that prosecutors will have to provide a motive at some point.

“Ultimately,” Bartley said, “the Commonwealth has to give us the information to understand what would make this man who has served so honorably in his community get to the point that he thought the only thing he could do to protect his wife and daughter was to take action on his own.”