Section Branding

Header Content

Many Palestinian citizens of Israel live in fear amid a backlash after Hamas' attack

Primary Content

This story is a part of an NPR series reflecting on a year of war and how it has changed life across Israel, the Gaza Strip, the region and the world since Oct. 7, 2023.

TEL AVIV, Israel — Walking through central Jaffa, a mixed Arab and Jewish district in southern Tel Aviv, there are shops with both Arabic and Hebrew signs, and many women wear hijabs.

Abu Yehya changes a bicycle wheel in his shop. He is a Palestinian citizen of Israel — a community of about 2 million people that makes up one-fifth of the country’s total population.

Abu Yehya says he’s always had a mix of Arab and Jewish customers and friends.

But since Hamas attacked Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, he says his Jewish neighbors view him with suspicion.

“The way they look at you is different now,” Abu Yehya says. “They walk in [to the shop], see you’re an Arab and walk out.”

Many Palestinian citizens of Israel live and work alongside Jewish Israelis, and speak both Arabic and Hebrew. Twenty of them were among the 1,200 people killed in last year’s Hamas attack, according to Israeli officials.

But many Palestinian citizens of Israel say they feel vulnerable living in an atmosphere of fear, facing a backlash from Israeli society and authorities after the Hamas attack just over a year ago.

Many in the community have relatives in the Gaza Strip, where the Israeli military's campaign in response to the Hamas attack has killed more than 43,000 people and injured more than 100,000 others, according to Gaza's Health Ministry.

Abu Yehya says he has lost relatives in the war in Gaza.

But while families of Israeli hostages taken by Hamas set up Hostage Square in central Tel Aviv — with tents, art installations and memorials — Abu Yehya says he hasn’t held any memorials for his killed relatives for fear that his Jewish neighbors would mistake his grief for support for Palestinian militants in Gaza. Palestinians in Jaffa say they try to avoid speaking about Gaza or their relatives there in public, he says, for fear of police reprisal.

“I don’t even dare to write the words ‘rest in peace’ on Facebook to mourn my cousin,” Abu Yehya says.

He says a Jewish man who was a good friend turned on him after the Hamas attack. “He told me, it would be better if we [Jewish Israelis] lived here without you [Palestinians],” Abu Yehya says. “I had respect and love for this man, but I can’t forget the way he looked at me that day. Full of racism.”

Who are Palestinian citizens of Israel?

During the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, more than 750,000 Palestinians fled or were expelled from their homes. Some of them took shelter in refugee camps in the Gaza Strip and elsewhere, which over the years turned into towns where generations of Palestinians with roots in places like Jaffa live.

The thousands of Palestinians who stayed in Israel were placed under military rule until 1967, with limited freedom to move in the country and the world. Israel also drafted laws to strip many Palestinians of their land and transfer it to state ownership.

In 2018, the Israeli parliament passed a law called the “Jewish nation-state,” which says that the right to exercise national self-determination in Israel is unique to the Jewish people. A legal rights group, Adalah, has documented over 65 Israeli laws that it says discriminate against Palestinian citizens of Israel or Palestinians who live in the Israeli-occupied territories on the basis of being Palestinian.

Today, many Palestinian citizens of Israel are prominent members of society, including scholars, doctors, lawyers and lawmakers in the Knesset, Israel’s parliament.

Mohammad Darawshe, an expert on Arab-Jewish relations at the Jerusalem-based Shalom Hartman Institute, says Palestinian citizens of Israel live in a hybrid world. They are viewed as traitors by some in the Arab world — including some fellow Palestinians — for not abandoning their Israeli citizenship in protest, he explains.

“[Non-Israeli citizen] Palestinians started seeing the Arab citizens as Israelis, mainly people that have gone through the Israelization process, and for Israel they are leftovers of the enemy,” Darawshe told NPR.

Darawshe says he believes many Palestinian citizens of Israel don’t want to live in a Palestinian state, and that the future of such a possible state is not encouraging.

But he says he believes many prefer living in Israel over other Arab countries or an uncertain future Palestinian state. “In Israel we are experiencing limited democracy, and also limited prosperity. Both of them are better than what you have in most Arab countries,” Darawshe says.

Yet those limited rights have become more restricted after last year’s Oct. 7 attack, according to rights groups.

A crackdown on free speech

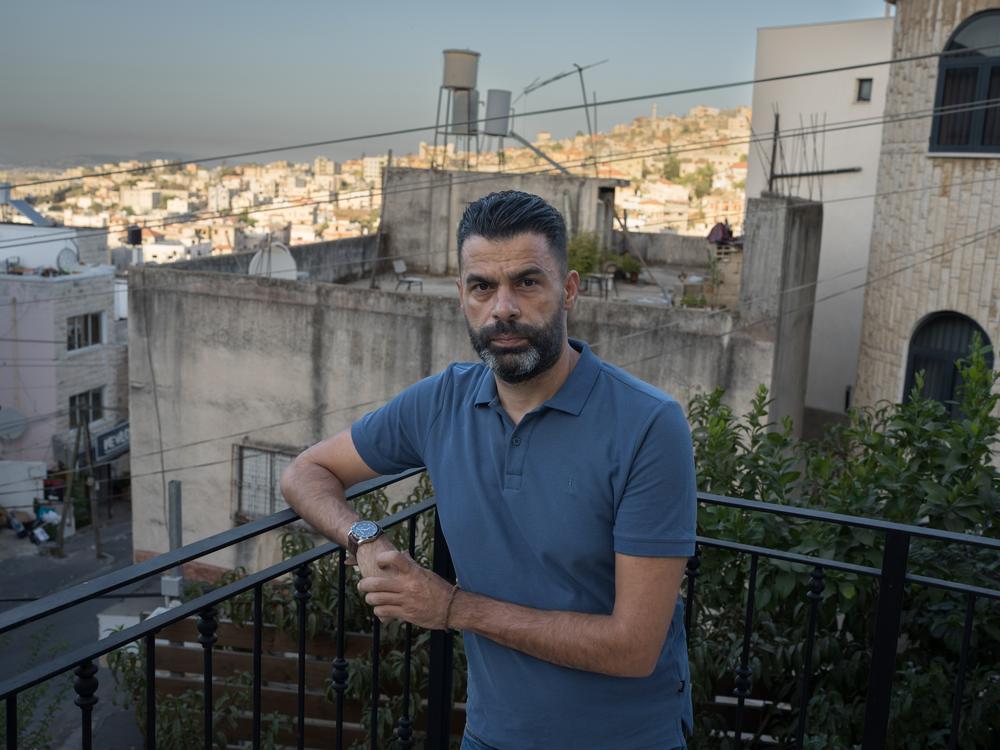

Ahmad Khalefa waves from his front door. It’s past 5 p.m. and it’s illegal for him to go any farther. The 42-year-old Palestinian citizen of Israel has been under house arrest for almost 10 months, two of those under night house arrest.

On Oct. 19 last year, Khalefa, a human rights lawyer, was arrested during an anti-war demonstration in Umm al-Fahm, his hometown in northern Israel made up of Palestinian citizens.

He says he was chanting slogans in support of Palestinian victims of the war, including one used in Palestinian demonstrations for over 30 years. The chant was: "Gaza, don’t sway, you are full of dignity and glory."

Suddenly, Israeli police stormed the protest, which Khalefa says was loud but nonviolent until then. Videos filmed by witnesses and posted to social media showed police arresting people, throwing stun grenades and shooting rubber bullets.

Khalefa says, as a community leader, the police came for him. “Where is Khalefa? Where is Khalefa? They were looking for me,” he says. He immediately surrendered to the police, he says, extending his arms in front of him to show he was unarmed.

What happened next took him by surprise.

“They took me from my shirt, ripped my shirt above me, and started beating me,” Khalefa says. “They put me on the ground, two or three officers, and started beating my ribs with their knees.”

Khalefa says the police searched his home that night, threatening his wife and going through his children’s backpacks and rooms.

Khalefa was charged with “incitement to terrorism” and “identification with a terrorist organization” based on that chant and other anti-war slogans. He spent four months in jail, where he says he was mistreated: beaten, given little to eat and forced to wear the same police-issued shirt for three months. He says the cells were overcrowded and filthy, and that he also witnessed the abuse of other prisoners.

“For me, it was much, much harder than when they beat me up, to hear people crying 24/7,” he says. “People were begging for their lives and crying. … The atmosphere was full of fear that you can die in any second.”

The Israeli police told NPR that it was not familiar with “the claims described” and that every prisoner has a right to file a complaint.

In February, the Israeli Supreme Court ruled that Khalefa was no longer a danger to Israeli society and put him under house arrest in an apartment he rented in Haifa for about six months. He wore an ankle bracelet, and his wife stayed with him assigned as his guarantor. Their children were still in Umm al-Fahm attending school, staying with relatives, and Khalefa only saw them on weekends. He was then released to his home in Umm al-Fahm under night arrest, where he awaits sentencing next year.

Khalefa says the whole situation confirmed what he knew all along about living as a Palestinian citizen of Israel.

“We are living in a political body that claims to be [democratic] state, but it is a Jewish democracy that we have no place [in],” he says.

Palestinian students and academics have also come under the crackdown on freedom of speech in Israeli universities, according to the legal rights group Adalah. The group says many students have been suspended, expelled or faced disciplinary action for inciting violence against the state of Israel by participating in street protests or posting social media messages against the war.

The Israeli Education Ministry hasn't responded to NPR's request for comment.

Court attitudes change

Myssana Morany, a lawyer with Adalah who represents Khalefa, says there's a harshness of the charges and sentencing makes it difficult to defend clients in free expression cases. She says changes in the judicial system after last year’s attack on Israel have left the courts where she works unrecognizable.

“Suddenly I felt like I don't have a common language with the court anymore. I’m standing there, arguing the same things I argued before that led to the release of a lot of people [and] I’m getting to a dead end, with the court, with the judges, with the attorney general,” Morany says.

She says even the judges are harsher when she’s arguing a case.

“They just look at me and say ... ‘What was before the 7th of October, isn’t what is happening after the 7th of October,’ ” she says.

Israel’s Justice Ministry has not responded to an NPR request for comment.

Nonactivists are also targeted

One Palestinian woman told NPR that her Jewish Israeli landlord reported her to the police for a social media post he thought meant she was praising Hamas. She said he was misinterpreting an Arabic word.

She asked NPR not to use her name because she said she feared for her security.

The single mother spent 11 months in jail on incitement of terrorism and charges of supporting Hamas.

In a separate incident in May, video of the arrest of Rasha Harami, a Palestinian beautician from Majd al-Krum, in northern Israel, circulated online after police filmed her being handcuffed and blindfolded, whimpering as the officers announced her charges.

The Israeli police said she was arrested for posting social media messages against the Israeli military. One post compared Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to Hitler for the war in Gaza.

Harami was released within 24 hours and placed under house arrest for five days.

There were 84 indictments for incitement to terrorism filed between 2018 and 2022, mainly against Arabs, according to the parliamentary Research and Information Center. Amnesty International says that since the war began last year, the Israeli state has filed hundreds of indictments against Palestinians for expression-related offenses under the Counter-Terrorism Law, mostly involving social media posts.

In the wake of the Hamas attack last October, Israel’s police commissioner, Kobi Shabtai, made his position clear: “Whoever wants to be a citizen of Israel, welcome,” he said, using the Arabic phrase for welcome. “Whoever wants to identify with Gaza is welcome, I will put them on a bus headed there.” (No Palestinian citizen of Israel is known to have been bused to Gaza under such circumstances; although, Israel did deport thousands of permit workers from Gaza back to the enclave after the war broke out.)

Sami Abu Shehadeh, a prominent Palestinian citizen of Israel from Jaffa, who served in the Israeli parliament, says he has experienced violence in his hometown, Jaffa.

He says he was attacked physically and verbally on the streets by Jewish Israelis, and that women who are visibly Muslim and Arab have received harsh abuse.

“Here in Jaffa, a lot of the Muslim women who wear scarves were attacked on the public transportation,” Abu Shehadeh told NPR. “Part of them are afraid of going to hospitals or see their doctor because they are attacked on the streets because they are not Jewish.”

Abu Shehadeh says he knew a man who worked at a supermarket who was fired via WhatsApp text message.

“Don’t come to work tomorrow, we have stopped hiring terrorists,” he says the text message read.

The worker wouldn’t speak to NPR or identify the supermarket for fear of reprisal.

This treatment has been confusing to some. Many Palestinian citizens of Israel are members of the community, including medical personnel who helped treat people who were injured in last year’s Hamas attack. “On the same day, they were rescued by Arab Palestinians,” Abu Shehadeh says.

Some Jewish Israelis say they understand the concerns of Palestinians in his city.

“Most Arabs are afraid of being arrested and harmed. They don’t express themselves freely,” says Yona Rosenbaum, a resident in the mixed city of Haifa.

A year of patience

In the Jabalieh Mosque in Jaffa, Imam Bilal Dekkeh leads about 10 men in afternoon prayers.

Palestinian Muslims come to find spiritual guidance from Dekkeh at a time of anguish.

But even the preacher says he’s avoiding any reference to the war.

“Any Friday sermon about Gaza, and the police will arrest you,” he told NPR.

Dekkeh says many in his congregation come to ease their pain over the war in private, and that he only has one thing to say: “I tell them to be patient,” Dekkeh says, “that there is a mighty God above.”

Crime stoking fear

A deadly shooting this month in the heart of Jaffa exposed these tensions.

At the same moment that sirens wailed during an Iranian missile attack on Israel, on Oct. 1, two Palestinian men from the Israeli-occupied West Bank opened fire at a Jaffa light rail station, killing seven people. Hamas claimed responsibility for the shooting.

Bystander Shay Peretz witnessed the shooting and called for police to search every Palestinian home in Jaffa.

“The Arabs of Jaffa are a danger,” he told reporters. “Anyone who harms us will be dealt with an iron fist.”

After the attack, news reports said one of the suspected gunmen ran into a nearby mosque.

Israel’s far-right national security minister, Itamar Ben-Gvir, said, “If a connection is found to the mosque, we need to close it, to demolish it.”

There was no connection, Israeli police later said.

Palestinian citizens of Israel felt like they were caught in the middle, even though Arabs were among those wounded in the Jaffa shooting.

Eran Nissan, a Jewish medic who treated the wounded, told Israeli TV that the Ben-Gvir was exploiting hatred in Israeli society.

“Jews and Arabs are trying to build a life together,” Nissan said.

It's a life that Palestinian citizens of Israel struggle to navigate as the war in Gaza continues.

Abed Abou Shhade and Yanal Jabarin contributed reporting from Jaffa, Tel Aviv. Itay Stern contributed reporting from Haifa, Israel.