Section Branding

Header Content

Why abortion referendums are also about the economy

Primary Content

Abortion rights and our bank accounts are inextricably tied, as those who study economics will tell you.

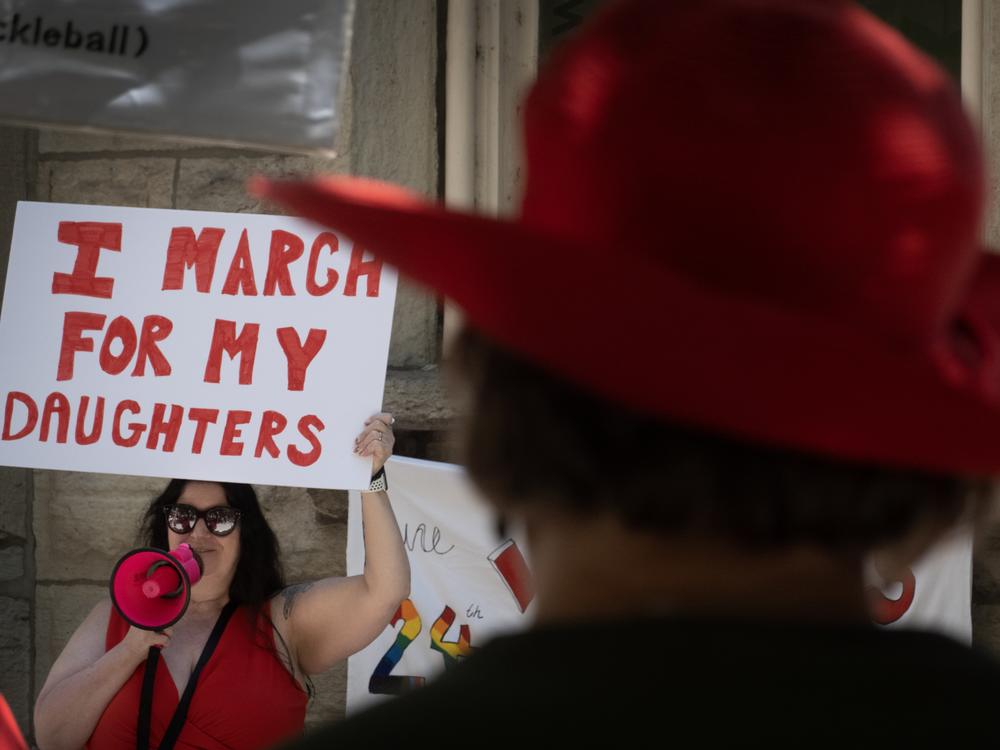

With abortion rights on the ballot in 10 states this year, not to mention some candidates who see women's purpose in society along traditional lines, many Americans will be casting a vote with consequences for women's role in the economy.

The link between reproductive choice and personal finances is clear for people like Janet Yellen, who is the United States' first female Treasury secretary and is considered to be one of the world's premier economists. At a Senate hearing shortly before the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022, Yellen testified that access to reproductive health care, including abortion, over the previous five decades had enabled many women to finish school and advance in the workplace.

"That increased their earnings potential. It allowed women to plan and balance their families and careers, and research also shows it had a favorable impact on the well-being and the earnings of children," she said. "Denying women access to abortion increases their odds of living in poverty or need of public assistance."

Many people who believe in the right to life from the moment of conception say that economics should not play a role in such decisions. In that same hearing, Republican Sen. Tim Scott of South Carolina criticized Yellen's economic framing as "harsh" and pointed to his own background.

"As a guy raised by a Black woman in abject poverty," he said, "I'm thankful to be here as a United States senator."

Access to birth control lets women "plan for careers rather than jobs"

Claudia Goldin last year became the first woman to win the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences as an individual, rather than as part of a team. She makes the sharpest case for how the ability to choose when to have children was the main driver behind a dramatic increase in the number of women entering the workforce and pursuing careers in the 1960s and '70s.

Goldin ties it to the birth control pill, which became widely available around 1970. It allowed women to delay childbirth and led to what she frames as a revolution in their personal economics. It also made it easier for women to delay marriage, which in turn, Goldin wrote, meant that they "could be more serious in college, plan for an independent future, and form their identities before marriage and family."

A wave of laws passed in that era protected women from discrimination in being hired or fired from their jobs based on their gender or whether they were pregnant. It was around the same time — 1973 — that the Supreme Court's landmark ruling on Roe v. Wade gave women the constitutional right to have an abortion.

Goldin wrote that during this period, women's horizons "expanded." They began investing in education and viewing work the way men did, which is that they would remain employed even after getting married and having children.

"They could plan for careers rather than jobs," she wrote.

And even though women today still earn less than men, the overall ratio of women's to men's pay has risen since the 1970s from 60% to 83%, and women outearn men in some sectors.

JD Vance: "make this a pro-family country"

The expanded horizons for women, as Goldin calls it, are not viewed as a positive for the country by all. For instance, Sen. JD Vance of Ohio, the Republican nominee for vice president, supports proposals that he says will help all American households. However, for some of Vance's critics, the subtext in measures he calls "pro-family" envisions more women staying home to rear children.

In a speech, Vance has said he wants to "make this a pro-family country, not just in the way that we vote, not just in the policies that we enact, but in the very structure of our country," calling the drop in American birth rates a "civilizational crisis." (The birth rate — measured as the number of babies born per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44 in the U.S. in a given year — has fallen by about 19% since 2007.)

More recently, Vance said on CBS News that he wants to boost the child tax credit to $5,000 per child from the current $2,000, for all families regardless of income. (Democratic presidential nominee Kamala Harris also has a proposal for increasing the child tax credit.)

Vance also introduced a bill last year, called the Fairness for Stay-at-Home Parents Act, that would prevent employers from reclaiming health insurance premiums from parents who didn't want to return to work after having a child under the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA).

Vance singled out mothers, not fathers, among parents as beneficiaries of staying at home. He criticized the law as "penalizing mothers who choose to prioritize their child's early development and recover rather than return to work within the 12 weeks provided under FMLA."

Vance's own wife, Usha, whom he met at Yale Law School, worked as a lawyer until he was named the Republican vice presidential nominee and she resigned "to focus on caring for our family." But he has drawn scrutiny over his comments on women, particularly one in an interview on Fox News where he said the country is being run by Democrats, corporate oligarchs and "a bunch of childless cat ladies who are miserable at their own lives."

Vance has also in the past endorsed a bill introduced in 2021 by Republican Sen. Josh Hawley of Missouri called the Parent Tax Credit Act. That bill proposed a tax cut of $6,000 for single parents and $12,000 for married parents. In essence, it provided a financial incentive for the institution of marriage by doubling the benefit.

Vance's campaign didn't respond to a request for comment about both proposals.

It is true that a household with two parents provides stability and leads to better outcomes for children. Some economists say it is specifically true for married parents. However, the reality is that marriage rates have fallen and about 2 in 5 children these days are born to single mothers, so such a policy would leave many families with smaller benefits.

Economists who have traced women's advancement, like Goldin, don't believe it is possible to return to that past where women fulfilled traditional roles. She recently told NPR: "Revolutions do not go backwards."

And the cost of diminished economic opportunities, Goldin and Yellen argue, hurts the prospects of all: the family, society and the economy at large.