Section Branding

Header Content

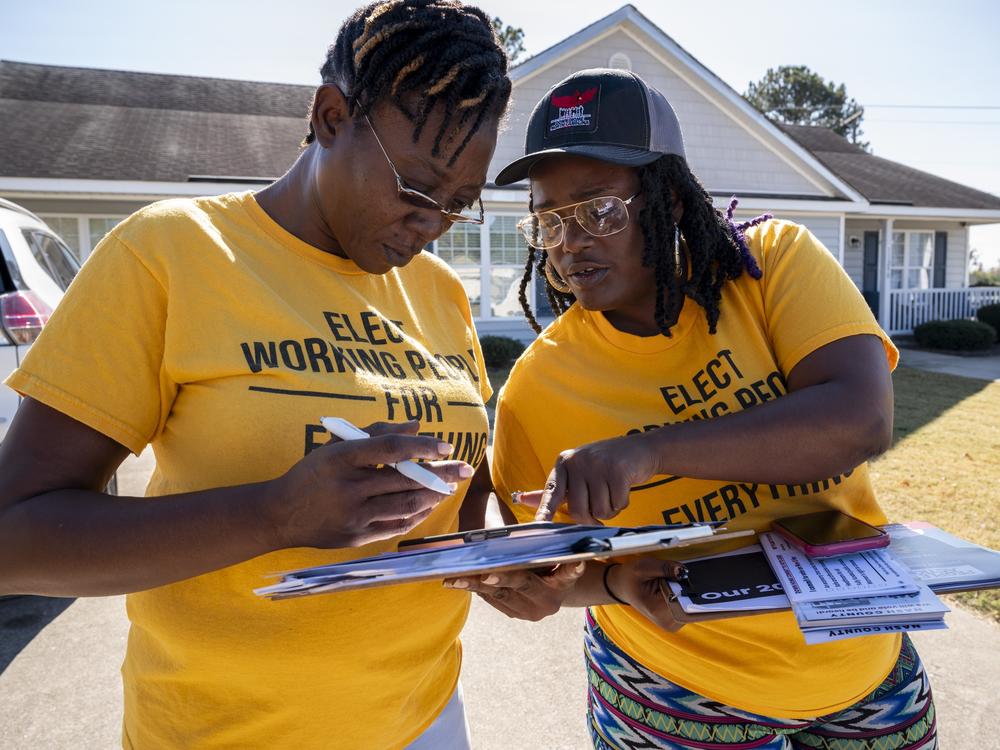

Support from rural Democrats will be crucial for Harris to win this swing state

Primary Content

Jakai Britton was not planning on casting a ballot this election season. When a group of door knockers came to his neighborhood, he wasn’t planning on having a conversation, either. But in the span of a couple minutes, he’d agreed to both.

Britton, a 28-year-old non-affiliated voter in Nash County, North Carolina, was pulling out of his driveway in a black SUV, airport bound, when a canvasser from the organization Down Home North Carolina approached his car.

“Can we get five minutes of your time?” door knocker Alex Cook asked. Her plea for five minutes turned into a plea for two minutes, and Britton said yes. From the passenger side window, while Britton’s car was still running, Cook made her case for why he should vote for the Democratic down-ballot candidates the organization had endorsed. She focused on the way the local races would impact healthcare, an issue that resonated with Britton.

“So, do we have a vote from you?” Cook asked.

“Yeah, you’ve got a vote from me,” Britton said.

To Down Home North Carolina, the stakes of the 2024 election are too high to let a potential voter like Britton go. Nash County is near-evenly divided between white and Black residents, and in recent presidential elections, it was near-evenly divided by its results. In 2020, President Joe Biden won the rural county by two-tenths of a point. In 2016, former President Donald Trump won it by the exact razor-thin margin.

In the small town of Nashville, where the group canvassed that day, it did not feel evenly divided. There were Trump signs everywhere, and plenty of MAGA flags. Still, Down Home found plenty of Democratic and non-affiliated doors to knock on.

“What I noticed is that there's a lot of people who want to stay out the way,” said Adon Bermudez-Bey, Down Home’s regional field director. “They see the Trump signs, they see what's going on in the school boards, city council. They're just like, ‘I'm going to stay out of it.’ We're trying to tell them there's an organization that specifically focuses on rural areas to pull those folks out.”

Bermudez-Bey said Down Home’s platform was “survival,” helping poor and working class people get basic needs met like housing and education. In an election season like this one, the organization is mostly focused on local races, but they endorse candidates up and down the ticket, usually Democrats. Most of their time is spent urging residents — especially residents of color — to get out and vote.

“They don’t open the door all the time,” Cook said. “So one out of 10 doors, you might get someone.”

North Carolina's state Democratic chair, Anderson Clayton, is also focused on turnout this election. The 26-year-old from rural Person County is the youngest state party chair in the country.

“Joe Biden lost the state by 74,000 votes in 2020, which we know is a field margin, and that can come from all of our counties across the state,” Clayton told NPR in October.

There are potential barriers to getting those votes. North Carolina has some of the most extreme partisan-drawn maps in the nation. The state’s governor, Roy Cooper, is a Democrat, but Republicans hold a supermajority in the statehouse.

Still, Clayton has made reaching out to rural Democrats a key part of her strategy. The stakes are clear: the Tarheel State has more rural voters than any other 2024 presidential swing state.

“I'm not going to win rural North Carolina this year. I'm trying to bring back margins in it,” Clayton said. “There's a difference in trying to talk to rural voters and talking to rural Democrats. I'm trying to talk to rural Democrats this year. People that showed up in 2008 that ain't showed up since because they haven't had somebody to vote for and they didn't feel like their vote actually mattered.”

Loading...

Back in Nashville, Down Home door knockers make their pitch to another resident. Sean Jones says he plans on voting, though in the presidential race, he hasn’t made up his mind. He said he’s leaning toward Vice President Kamala Harris.

“I just recently went to go see my brother in prison this weekend, and he was kind of on my head about voting,” Jones said. “He wanted me to vote for Trump, but I still wanted to vote for Kamala. So I'm still trying to, like, look into the politics as far as what’s what and who’s who.”

So soon before Election Day, finding a true undecided voter can feel like a rarity. But Down Home encounters them all the time, even within their own ranks. Adon Bermudez-Bey, speaking only for himself and not for the organization, told NPR he’s also undecided on the presidential race — even as he led a group of canvassers for an organization that has endorsed Harris.

“I don't know if I'm voting for Kamala yet, just full transparency,” Bermudez-Bey said. “But I know that I'm definitely not voting for Trump.”

Bermudez-Bey cited his concerns about Harris’ time as a prosecutor in California, and her support for Israel during the ongoing war in the Middle East. He set a deadline for himself: By the last day of early voting in North Carolina, he’ll decide between Harris or a third-party candidate.

In the meantime, though, Bermudez-Bey said he still sees the merits of a Harris presidency — at least for Down Home’s goals.

“No, it's not going to be perfect, but it's going to be a lot easier for us to organize under her presidency than Trump's,” he said.

The motivation of voting against Trump, rather than for Harris, was in the air a dozen miles away at an early voting site in Rocky Mount, Nash County.

“I just feel like Donald Trump is for billionaires and not for working class people,” said voter Lynn Jones, who spoke to NPR after casting her ballot for Harris.

Her neighbor Donnell Jones, no relation, was by her side. He had just voted for the first time in his life. Lynn said the two of them had had a series of conversations in recent weeks about going to the polls together.

“I just thought, you know, he was at an age where this just should have happened a lot sooner,” Lynn said. “But I know sometimes people are stuck in their ways, so I didn't pressure him. Just, ‘Hey, let's go vote together then.’”

That resulted in one more vote for Harris.

“I voted for the lady,” Donnell said.

If Democrats win Nash County, and win North Carolina, it will be through thousands of interactions like what Down Home is doing — and on a more casual level, what Lynn Jones did with her neighbor Donnell. The key will be nudging others to show up and vote, regardless of how disengaged or skeptical they were at the beginning of those conversations.

Early voting in North Carolina ends on November 2. So far, more than 3.6 million voters have cast their ballots.