Section Branding

Header Content

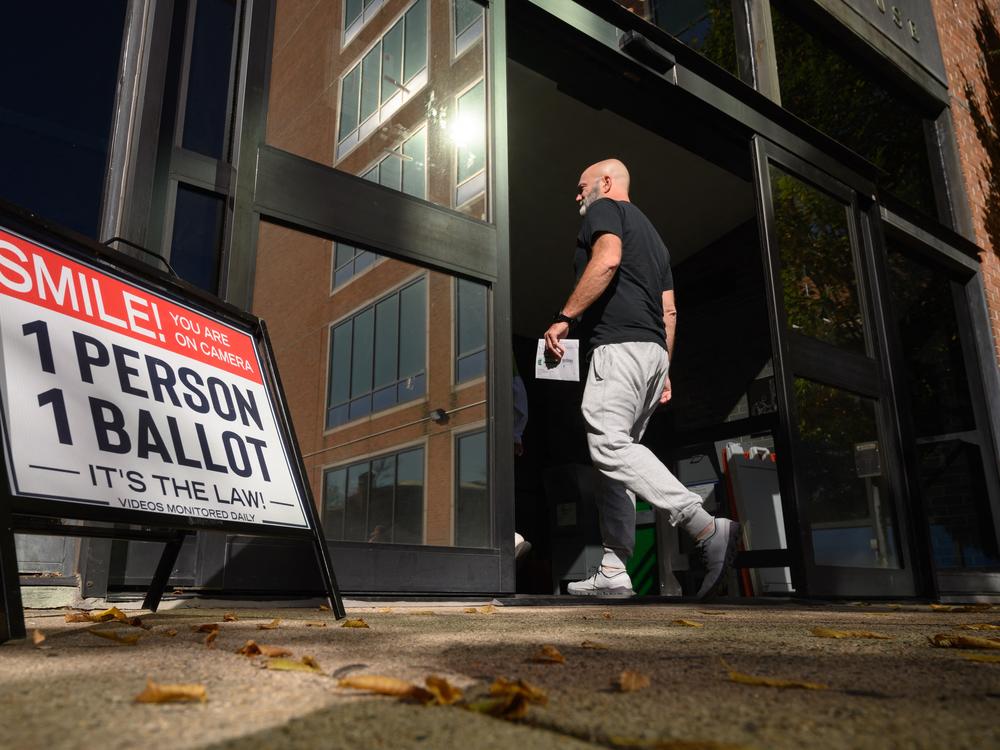

An influencer thought someone dropping off ballots was ‘suspect.’ It was the postman

Primary Content

Two days before Halloween, a Pennsylvania postal worker was delivering a box of mailed-in ballots to the Northampton County Courthouse. A man filming with his phone began asking questions and followed the postal worker into the building.

The man doing filming was told that the man with the box of ballots was a postal worker.

"I dunno, apparently he's with the post office, but that looks very suspect," said the man filming, zooming in on what he said was "an obscene amount of ballots."

The video then zoomed in for a closeup of the postal worker’s face. As of Nov. 2, it had nearly six million views.

County officials in Pennsylvania confirmed to local news outlets that the man filmed in the video was an acting postmaster, doing his job. After the video went online, he began receiving threats.

Even before Election Day, unsubstantiated rumors about voter fraud are beginning to focus on specific public servants and voters. In 2020, this kind of online activity led to harassment, threats and ultimately, played a role in fomenting the Jan. 6, 2021 riot at the U.S. Capitol.

But this year, videos like these are appearing in a dedicated community on Elon Musk's social media platform, X, formerly Twitter, and inviting more of the same type of speculation that can result in threats and harassment.

Sharing concerns and trying to make sense of the voting process is a normal part of a free and fair electoral process, said Renée DiResta, an associate research professor at Georgetown University and an expert on election disinformation. "But there's a really big difference between discussing a concern and putting somebody's face up and accusing them of treason."

In 2020, DiResta said many major social media platforms did more to try to add context and amplify information from credible sources. Under pressure from Republicans, many platforms have backed off on those policies since then. Perhaps the most important factor has been Twitter’s transformation into X since billionaire Elon Musk bought it in 2022 and has steadily turned the platform into pro-conservative social media site with minimal moderation policies.

"I would say the major difference this time, though, is that X is hosting the communities where this sort of effort at sense-making is taking place," said DiResta.

Over this past year, Musk has become a major backer of Donald Trump's campaign and himself become an avid sharer of election fraud rumors on X. This month, the super PAC Musk founded to support Trump created a dedicated space on the social media platform to share crowdsourced instances of potential election fraud, where it has quickly amassed a large following of more than 60,000 users.

"Most of the people who are responding to the posts are convinced that the election is being stolen and so feels a little bit more like a place where they're trying to just gather evidence to prove the thing that they've already decided has happened," said DiResta. "And they're concerned about that because they keep hearing it from political elites that they trust - people like Donald Trump and people like Elon Musk."

Each individual post, DiResta said, is woven into a much broader narrative by politicians and pro-Trump influencers, often with conspiratorial overtones. The amalgamation is meant to imply that evidence of voter fraud is massive and insurmountable, despite more than 60 court cases, multiple recounts and ballot audits, that found no evidence of significant voting irregularities in 2020.

X did not respond to a request for comment from NPR.

Burned by election lies

The impact on the everyday people who get tangled up in these conspiracy theories is profound.

The legal nonprofit Protect Democracy helped file a number of defamation lawsuits against election deniers after the 2020 election, "on behalf of people who found themselves suddenly being lied about in the public sphere for claims that they were breaking the law when they were not breaking the law," said Protect Democracy counsel Jane Bentrott.

Pro-Trump figures and partisan media organizations like One America News publicly retracted allegations and reached settlements with the people they had falsely accused of election fraud.

One prominent case Protect Democracy is involved with is a defamation suit against Trump's then-attorney, former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani, who baselessly accused two Georgia election workers by name of manipulating ballots.

Giuliani was found liable for defamation and a jury awarded the pair $148 million last year.

"The flame that Giuliani lit with those lies and passed to so many others changed every aspect of our lives. Our homes, our family, our work, our sense of safety, our mental health," said Shaye Moss, one of the workers, after the jury handed down its verdict.

"As he learned," said Bentrott, "and hopefully others who are paying attention learned, folks who accuse others falsely of breaking the law can have substantial consequences for those lies."

But even successful defamation cases often take years to resolve and Giuliani has yet to pay the women anything.

Protect Democracy made an effort to hold high profile figures like Giuliani accountable for spreading false accusations. But overall, the media landscape those influencers are part of has remained intact, according to DiResta.

"What you're seeing is a pipeline by which somebody makes an allegation, usually a small account, a person with a very concern that feels very real to them, but it's picked up by a person who has maybe tens to hundreds of thousands of followers."

DiResta has studied the way the January 6th Capitol riot was motivated in part by beliefs in the messages this pipeline generated.

The day after posting the video of the Pennsylvania postal worker, its creator wrote on X that if the subject of his video did turn out to be just a public servant doing his job, "I'll take this down and issue a correcting statement. We are after the truth, whatever that may be." As of Nov. 2, the video remains online.

DiResta said she's confident American election officials are better prepared for what's coming this election, but ultimately, "The tone is set still at the top. The people on social media are able to come up with evidence, but they're doing it to fit the frame set by the political leaders."