Section Branding

Header Content

Sikhs march across California urging protections against threats from India on U.S. soil

Primary Content

About 30 people are walking along a dirt path between a rural road and a persimmon orchard, kicking up dust with each step. Children run towards the front of the march, where a group of older men with turbans and thick beards keep the pace at a steady clip.

For three weeks in October, a group of Sikhs — some joining for just an hour or a day — have walked 350 miles up the spine of California’s Central Valley from Bakersfield to Sacramento. They stopped at Gurdwaras, or Sikh temples, along the way. The journey, organized by the Sikh advocacy group Jakara Movement, ended on Friday with a rally that drew a crowd at the state capitol.

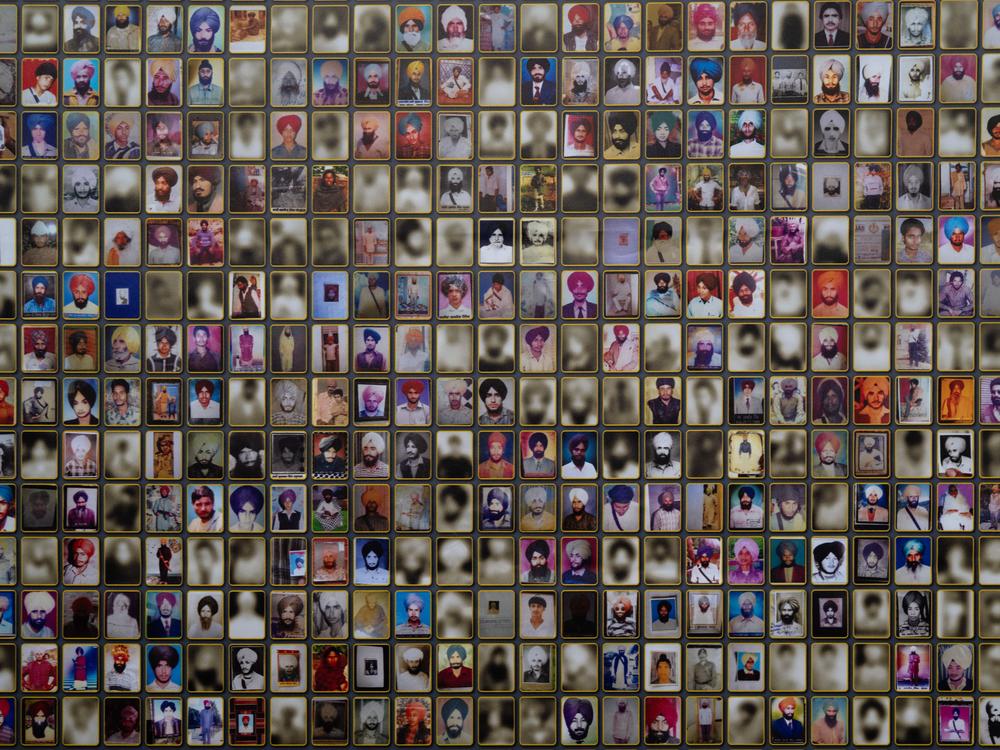

The events commemorated a Sikh massacre that happened in India 40 years ago. Organizers also sought to call attention to growing threats the Sikh community says have followed them here in the U.S.

Sikhs have been farming in the Central Valley for over a century, but many fled here in the years after 1984. That is when former Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi sent the army to occupy the Golden Temple, the holiest of Sikh sites, to rout out separatists who were agitating for their own Sikh state, a place they called Khalistan. In response, Gandhi’s Sikh bodyguards assassinated her. What followed were anti-Sikh riots that killed thousands, and a decades-long effort by the Indian government to stamp out an armed Sikh insurgency.

Last year, the California Legislature recognized what happened in 1984 as a genocide. A similar resolution was introduced this month in Congress.

“My mom came to Modesto from Punjab in 1984, you know?” says Jakara’s Simarpreet Singh. “She lived through that.”

He says many younger Sikhs grew up in the shadow of that trauma.

“They left India to find protection here, to find peace here and now that same government they fled is sending folks here to the U.S. and Canada to essentially assassinate those same folks' children and grandchildren.”

A growing threat

In Canada last year Sikh activist Hardeep Singh Nijjar, was assassinated in a Gurdwara parking lot. Canada alleges that India’s Interior minister, who is also the chief aide to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, was behind the murder. In New York last year, the FBI says it stopped another assassination plot against a prominent Sikh activist, Gurpatwant Singh Pannum. Two Indian nationals have been indicted, one of them a former Indian intelligence officer. India denies involvement in either case.

These incidents are both examples of alleged Transnational Repression, known as TNR. The FBI defines TNR as foreign governments working in the U.S. to silence, harass, or even kill people from the diaspora.

Standing in the Ceres Gurdwara after a long day of walking, Simarpreet Singh says it’s a scary time to be a Sikh.

“We have evidence that the Indian government is going around literally naming people who are in this building today, calling them things like 'they're a terrorist,' because we represent something that they are trying to repress.”

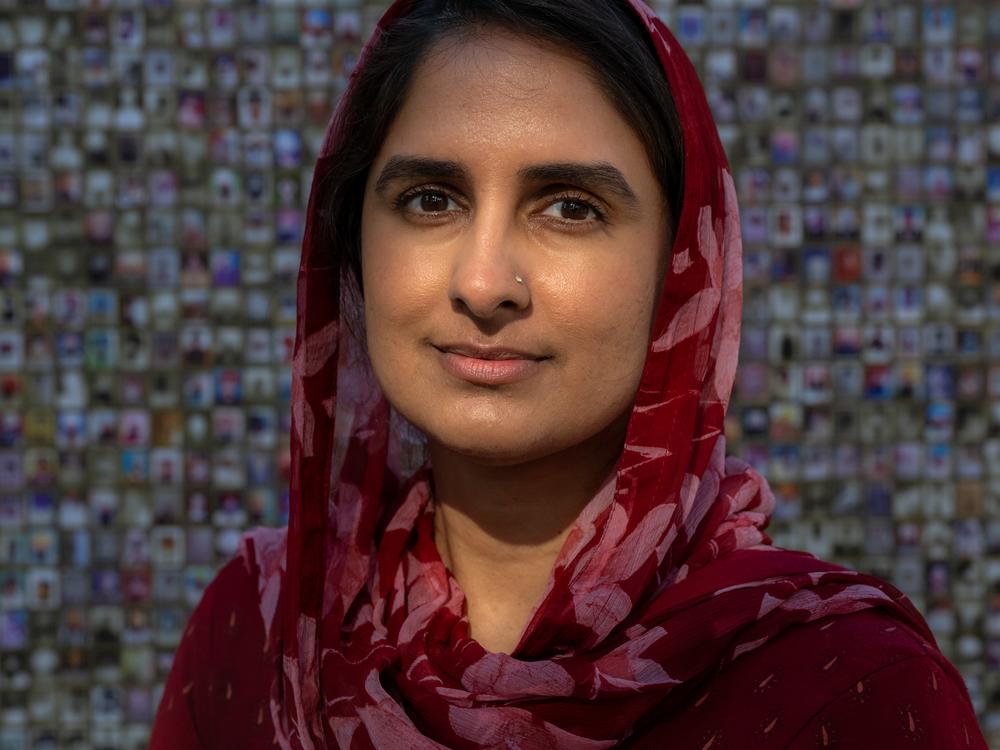

Both the assassination and the alleged assassination attempt were made on members of the group Sikhs for Justice. Earlier this year, someone fired at a car on a California highway. The three men inside were members of that same Sikh group, though the incident is still under investigation. Sikhs for Justice continues to advocate for an independent Sikh state of Khalistan. The Indian government says they are terrorists, but the group says they are peacefully seeking self-determination. That includes an ongoing non-binding referendum where Sikhs are voting to show support for a Khalistani state. But it isn’t just Sikh separatists facing threats, says Assemblywoman Jasmeet Bains, the first Sikh American elected to California state office.

“This is an attempt by the Indian government to annihilate and destroy an entire community,” she says.

This year Bains introduced legislation that aims to better track Transnational Repression in California, including training local law enforcement on how to deal with the threats.

“Right now there are attempts by the Indian government to silence and to push back against the freedom of speech that is being carried out by Sikh Americans,” she says. Critics of the Indian government say democracy is faltering under Modi and his Hindu nationalist government, which they say attacks and marginalizes other minority groups and religions, including Sikhs and Muslims.

Opposition to the Transnational Repression Bill

After proposing the bill, Bains says she received death threats and other messages accusing her of protecting terrorists. She says the TNR bill was killed in committee after a flurry of opposition letters from Hindu advocacy organizations. They claimed that naming India in a list of countries engaged in TNR would put a target on the backs of Hindu Americans. One of the opposing groups is CoHNA -- or the Coalition of Hindus in North America.

“Anti-India hate or laws, if they came to be, would be used as a cover for anti-Hindu hate,” says CoHNA’s Pushpita Prasad.

Prasad points to a spate of vandalism incidents at Hindu temples across the Bay Area last year, including graffiti that called the Indian prime minister a terrorist, and said “Khalistan Zinzabad” -- which means “long live Khalistan.”

Prasad says hate towards Hindus has been largely ignored by the media and law enforcement.

“We know that they won't go after people who attack Hindus, but they might start coming after Hindus who are advocating for equal treatment and human rights for Hindus, because whatever I say could be twisted into saying, ‘oh, I'm an agent of this and that.’”

Bains says that is not how the bill would work.

“This bill didn't call out any religion or dialect, it called out a country,” she says. “India belongs to a lot of different religions and dialects and ethnicities, not just one.”

Bains plans to reintroduce the TNR bill next session. In September, Congressman Adam Schiff introduced the federal Transnational Repression Reporting Act, after the 2023 attempted assassination of Pannun.

A meeting and an accusation

Naindeep Singh, whose group Jakara Movement organized the October march, says the fight against TNR and other suppression of Sikh activism has become personal in the last year. Singh says neither Jakara Movement nor he advocate for an independent Sikh state, though he supports the right of others to speak out for that cause.

Singh was born and raised in Fresno, where he’s an elected school board member. He recalls learning about a meeting that happened last fall – a meeting he wasn’t at, but where his name was mentioned.

The meeting between a group of Hindu residents, the Fresno mayor and then-police chief Paco Balderrama took place last year.

Balderrama says during his tenure as police chief it was common to meet with representatives from Fresno’s diverse communities. What was uncommon were the Hindu residents' accusations that Singh and two other prominent local Sikh community members were somehow involved in criminal activity, even potentially violent. He says he felt like he was being pushed to investigate them.

“There’s no smoking gun,” Balderrama says. “I'm not going to go out there and go after these three people that they named because simply -- I don't have enough information to say that they've committed any crime.”

He says back then he didn’t understand the tensions between some in the Hindu and Sikh communities.

“Now, understanding the political impact that it has, you know, I maybe see a reason for them coming forward and saying, hey, ‘they did this’ when maybe they didn't,” Balderrama says.

Earlier this year another Hindu advocacy group, the Hindu American Foundation or HAF held a training on Hinduphobia for some California police chiefs and DA’s. According to HAF’s LinkedIn, representatives from the Justice Department and Homeland Security were also there. HAF’s training materials call Sikhs for Justice a hate group and suggest law enforcement “monitor the social media platforms for US-based groups and individuals with ties to Khalistan terror groups who advocate violence and fundraise in furtherance of Khalistan." They also ask law enforcement to "investigate Khalistan attacks against Hindu temples and devotees as hate crimes."

In a public statement, leading Sikh advocates say the trainings push misinformation, adding that there is "no evidence that pro-Khalistan or Sikh individuals are responsible" for the vandalization of Hindu temples in California. HAF declined to comment for this story and has strongly denied they have any connection to the Indian government.

At heart is who gets to define who is a terrorist, Singh says. He says training around Transnational Repression is best left in the hands of the Justice Department.

Correction

A previous version of this story misspelled Simarpreet Singh's first name.