Section Branding

Header Content

How a staffing shortage can make special education jobs more dangerous

Primary Content

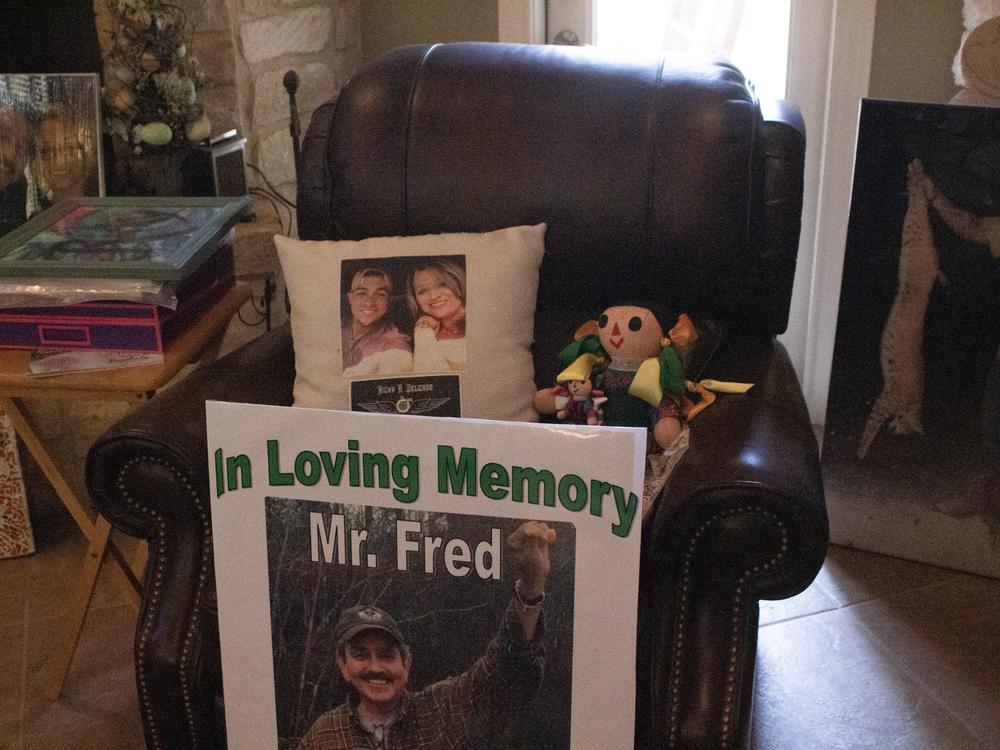

Every so often, Margo Jimenez says, her husband would come home from work with injuries.

"One day, he came home with a black eye, his glasses were broken, and he had bites on his arm," Margo recalled. "I said, 'Well, did you report it?' He said, 'No.' I said, 'Why not?' He said, 'Margo, because it happens all the time.'"

Fred Jimenez worked as a special education instructional assistant for the Northside Independent School District in San Antonio. He helped students with disabilities meet their learning and physical needs, and his job involved everything from diaper changes to helping students with hands-on instruction to managing violent outbursts.

On Feb. 7, one of those violent outbursts sent Fred to the hospital.

Fred was pushed by a high school student who has a cognitive disability. He fell and hit his head, and it led to a brain bleed.

He died 10 days later without ever waking up.

"I literally have no one since Freddy passed away," Margo said.

"Every day is a challenge for me, every day, every single day, all day. So I just do the best that I can with what God's given to me."

Fred's story is an extreme case, but the situations he faced in the classroom are a common story.

Students receive special education services for a wide variety of disabilities. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, most students with developmental disabilities aren't any more aggressive than other students. But for some, their disability can lead to frustration and, in turn, aggression. Other students may have disabilities that include a tendency toward aggressive behavior.

"It's not surprising," said Susan Dvorak McMahon after hearing about the injuries Fred received before his death.

McMahon, a psychology professor at DePaul University, studies violence against educators and has conducted national surveys of educator experiences. Among her findings, published last year: Special educators are more likely to experience violence or aggression from students.

"These issues have been going on for a while, and because we asked teachers about their worst, those most upsetting experiences, we read a lot of responses that are really – they're very difficult to read," McMahon said.

There isn't a lot of research into how often special educators are hurt at work, but a Pennsylvania study published in 2014 found special educators were nearly three times as likely as general educators to be physically assaulted by students.

That can make it harder for school districts to hire special education staff, at a time when schools across the country are struggling to fill these positions. A recent federal survey found, nationwide, special education vacancies are the most difficult for schools to fill. District officials told NPR that's also been true in Northside.

How staffing shortages can lead to unsafe conditions

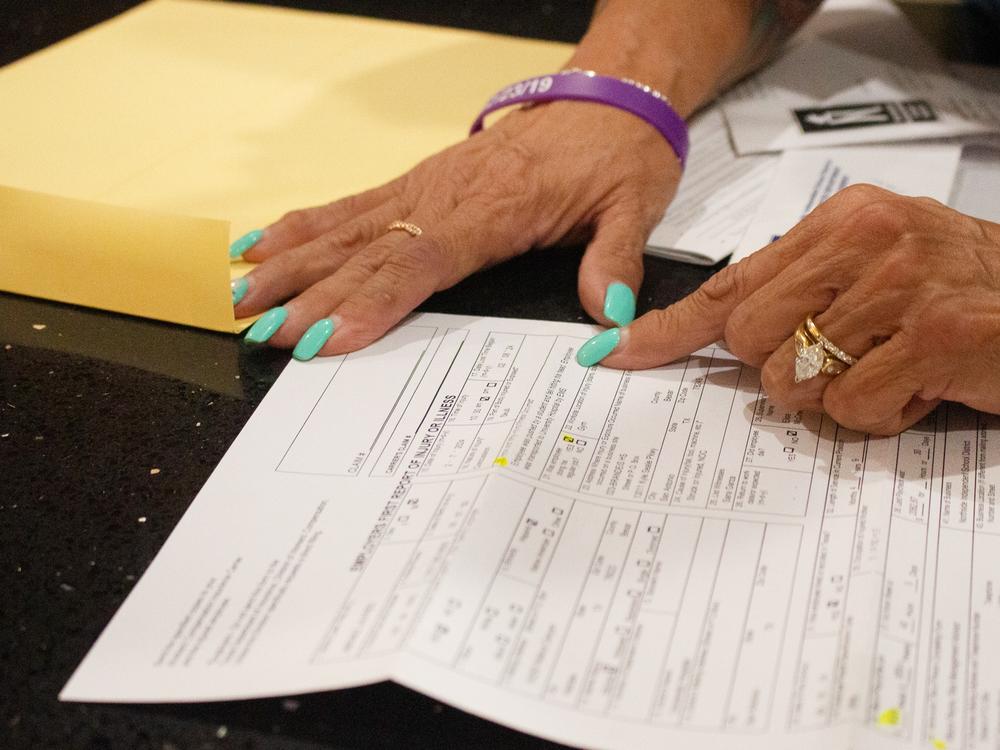

After Fred's death, his colleagues filed an internal complaint with the Northside Independent School District alleging that his death was part of a widespread pattern of student-caused injuries in special education classrooms.

Exhibits full of photos and email exchanges paint a picture of how the district's staffing shortages can lead to unsafe conditions and serious injuries.

Special education teacher Sheree Kreusel signed the complaint.

"I've had so many injuries," Kreusel said. "I've had three concussions, two broken noses, stabbed in the stomach, numerous bites, scars from bites. And that's just kind of a normal thing, unfortunately."

Kreusel worked with Fred before he moved to his final job at a high school. She teaches middle schoolers with cognitive disabilities, and for the past 15 years she's worked in a classroom that's only for students with higher levels of need.

She said she loves her students, and doesn't blame them for hurting her. Many of them have their own triggers, and Kreusel says she does her best to learn them. But she isn't always able to avoid an outburst.

"The student may be aggressive, but it doesn't mean they are targeting you because they hate you," Kreusel said. "That's usually not the case. It's usually something that has happened, and they might be nonverbal. They can't express it, and they just blow up."

When that happens, the teachers' complaint says, there isn't enough staff to address it.

Boston University researcher Elizabeth Bettini studies special education. She says when it comes to students who are prone to aggressive behavior, "You really need three people to be involved. You need two people to be part of keeping the students safe, and then you need a third one to collect data," or document what's happening.

But Kreusel said the district's staffing shortages means educators are sometimes alone in the classroom. The district acknowledges this does happen.

Low pay makes it hard to hire and retain staff

Northside Independent School District officials said they can't comment on the complaint while it is ongoing. However, Tracy Wernli, who oversees special education services for the district, agreed to answer more general questions.

She said Fred Jimenez was a "very well-loved instructional assistant in our district," and described his death as a "horrible, horrible event" and "absolutely devastating."

She also acknowledged the district has been struggling to hire the special education staff it needs, and a big reason for that is money. Wernli said the special education funding they get from the state and federal government isn't enough to cover their costs.

"That's a big key part," Wernli explained. "We spend a lot more than what we're given."

Northside's starting pay is less than $16 an hour for instructional assistants. Wernli said they can't afford to pay more. But for a lot of people, that's not enough compensation for a job that can be physically and emotionally demanding.

"There are people that do that and do it with passion and love it, and there are people that it's just not for them," Wernli said.

Kreusel, the teacher who worked with Fred, says she knows limited funding and staffing shortages are a challenge for many districts. But it doesn't change her reality.

"I'm afraid what happened with Fred – people hear about that, and they don't want to do this job. I mean, they can get paid more working at Chick-fil-A than being an instructional assistant," Kreusel said.

She thinks she and her colleagues will continue to get hurt until the district hires more instructional assistants and pays them well enough that they're willing to stay.

Audio story produced by: Janet Woojeong Lee

Audio and digital stories edited by: Nicole Cohen