Section Branding

Header Content

Mississippi communities scarred by ICE raids fear future under Trump

Primary Content

MORTON, Miss. — When Brandy Freeman is asked about what happened here five years ago, she stops in her tracks.

"It was horrible," Freeman says, her voice trembling as she tears up. Her eyes lose focus on the items inside the small thrift shop where she's browsing for used furniture. "It was really horrible," she whispers.

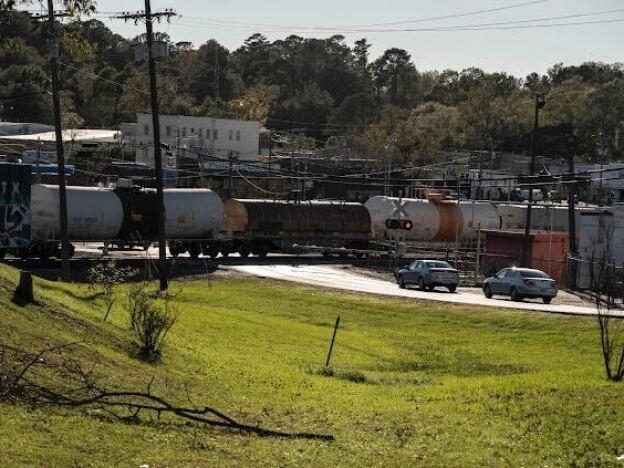

It's Saturday morning, and people are at home watching the 'Ole Miss' football game. Other than the hum of the Koch Foods poultry processing plant on the other side of the railroad tracks, it's quiet in this small city 30 miles east of Jackson.

That wasn't the case on Aug. 7, 2019, when seven poultry plants in central Mississippi, some of the biggest employers in the region, were raided by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Authorities arrested 680 workers, more than half from plants right here in Morton.

Freeman's partner wasn't detained that day. But he is in the country illegally working at a chicken plant, so they've talked about the possibility of it happening again– and about what it would mean for their 3-year-old son.

"It's a constant worry," she says.

A community on-edge

As President-elect Donald Trump gets ready to serve a second term, he and his advisers have said workplace raids will be restarted as part of their promise to carry out the largest deportation operation in history. The Biden administration had stopped workplace raids, although it continued removing immigrants with targeted operations.

This promise has left people in the area anxious about the deep impact new workplace raids could have on the community's psyche and the economy.

"What will happen if all our people get deported?" asks Lorena Quiroz, the executive director of the Immigrant Alliance for Justice and Equity, an organization that advocates for immigrant rights in Mississippi. She wonders whether Americans understand the extent to which the slaughtering and packaging of poultry depends on the undocumented workforce.

"Who is going to do all of that? Where are you going to find that pool of workers that are willing to work, quickly?"

Quiroz says that since the presidential election in November, she has received calls from people worried about potential new workplace raids in the area. "Our whole focus has been this: preparing, getting ready, making sure that we have resources," she emphasizes.

Trump's team says they'll first go after migrants with criminal records and final orders of deportation. Tom Homan, Trump's incoming border czar, has suggested people who have been ordered to leave the country but don't, become fugitives.

During the raids in 2019, most of the migrants picked up by ICE didn't have a record. Out of the nearly 700 people detained, about 230 were removed from the country under prior removal orders and other causes, according to the Mississippi Center for Justice.

Local immigration activists told NPR that agents also briefly detained people with work permits.

It was the first day of school

"It makes me want to cry if I just think back, because it was a lot of pain," says Kimberly Trujillo, an interpreter at a local dental clinic.

"We saw kids suffer, husbands, wives, and it's not something that should happen," says the longtime Morton resident. "Nobody deserves this."

Before the raids, Trujillo, who is fluent in Spanish and English, served as an unofficial translator for neighbors and friends who needed help filling out paperwork or making phone calls. Right after the raid she says her phone "blew up" with calls from people pleading for help in finding their loved ones.

Many ended up in detention centers near New Orleans. The Department of Justice says they quickly released single parents, pregnant women, and breastfeeding mothers — many with ankle monitors.

But kids whose parents worked at the poultry plants returned from the first day of school to empty homes.

This is what everyone remembers as being the worst part of the raids.

"When I came home from work, my house was full of kids," Trujillo recalls. "I had four of my godkids at the house because their parents were taken."

Scott County Sheriff Mike Lee describes the day as "pretty frantic," a feeling that lasted a couple of days as Lee and his deputies knocked on doors to take kids to a local church where families were being reunited.

"I never wanna make it as if I'm criticizing the men and women that work for ICE, but the planning could have been better," Lee says. "We had kids that were coming from schools and the parents were not gonna be at home, and these were young children."

Two days after the raids, then-President Trump was asked by reporters why there "wasn't a better plan in place to deal with the migrant children."

His response was a warning for migrants with no legal status.

"I want people to know that if they come into the United States illegally, they're getting out," Trump told reporters. "This serves as a very good deterrent."

Sheriff Lee says his agency will work with the federal government if it's required to carry out mass deportations and workplace raids.

But he says such actions "would severely hurt this area of Mississippi" by eroding the trust between his department and the community. This county is about 15 percent Hispanic according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Economic and cultural impact lingers

Workplace raids have also hurt small businesses in Morton.

Todd Hensley, who owns the thrift store in downtown Morton, says if unauthorized immigrants were deported again, he'd lose 50 percent of his business.

"I'm gonna be aggravated because everyone would be gone, and I'm not gonna make any money," Hensley says. "I might close down if they leave — it'd be that serious."

Even so, Hensley, like the majority of voters in Scott County, cast his ballot for Donald Trump.

Sofía Hernandez is the owner of María's Mercado, a Mexican restaurant and convenience store in downtown Morton.

"We were affected because many people were taken away, and our sales went down," she says in Spanish. "The whole town of Morton experienced sadness and pain. You can still feel it to this date."

She used to take up to 80 lunch orders a day, she says. After the raid, a lot of her customers never came back to Morton. The food orders went down to zero, and she had to lay off employees.

But the impact to Koch Foods was less noticeable. The plant here halted production for only half a day, and hosted a job fair later that week to fill the vacancies.

The company didn't respond to a request for comment for this story, but in a statement in 2019, the company denied any allegations of wrongdoing and said it adhered to federal labor laws when verifying the immigration status of employees.

At least four managers at two other companies faced federal charges related to the raids, including identity theft, harboring people who have entered the country illegally and fraud. According to court documents, almost all those charges were dismissed. Of the three sentenced to probation, two were fined $1,500.

José Gaspar used to work at one of the chicken plants that was raided. On that day, he was assigned to a later shift, so he missed the ICE agents.

After the raid, he says, people didn't want to leave their homes and Morton turned into a ghost town. Some moved to other states; others went to Mexico.

"Your people, your friends, your work family — that after years of working together you become a family — suddenly disappear," he says. "You are left alone."

Gaspar says he's worried it could all happen again.

Constant fear for the future

El Pueblo, a nonprofit organization that provides legal assistance to immigrants, is trying to help to ease the fears.

"We can't predict the future, but we can at least help people prepare," says Executive Director Mike Oropeza.

Oropeza's group, which has community centers in towns affected by the 2019 raids, is helping parents complete guardianship and power of attorney paperwork for their kids in case they are deported.

"Our goal is to alleviate some of the fear," she says.

El Pueblo has hosted know-your-rights events during Spanish-language Masses, visiting local churches and handing out workbooks to help people plan ahead. Oropeza met with the school district in Forest, Miss., to make a game-plan in case kids end up stranded again.

Baldomero Orozco-Juarez and his wife, Silvia García, have been making plans for their two children to be looked after in the event of another raid. Their kids are U.S.-born citizens.

During the 2019 raids, Orozco-Juarez was arrested, detained in a facility in Louisiana for 11 months, and deported to Guatemala. But after 18 months and three attempts, he made it back into the U.S. and now works at a different poultry plant in the area.

Orozco-Juarez says people who are skeptical about Trump's mass deportation promises and think it will only target violent criminals or be conducted in border towns have not lived through such a traumatic event.

"This government is really going to fulfill its promises," Orozco-Juarez says. "Those of us who have gone through this are scared."

He says he wants only one thing: to be left alone and to be able to continue to work to provide for his two kids.

NPR's Liz Baker contributed to this story.