Section Branding

Header Content

Judge decides lawsuit wanting Confederate’s name restored to a Fort Moore memorial

Primary Content

A lawsuit filed by the Columbus-based National Ranger Memorial Foundation to restore the name of a Confederate officer to the memorial and to the elite Army unit’s hall of fame at Fort Moore has been dismissed.

U.S. District Court Judge Clay Land issued the order Monday to grant the U.S. Department of Defense’s motion to dismiss the lawsuit the foundation filed last month.

Land heard arguments in the case Thursday at the federal courthouse in Columbus.

Background for the National Ranger Memorial Foundation lawsuit

As the Ledger-Enquirer reported in June 2023, the Fort Moore garrison commander directed the foundation to remove the name of Confederate Col. John Mosby from the memorial and the hall of fame as well as three other Rangers (William Quantrill, George Bowman and Jackson Bowman) associated with the Confederacy from pavers on the walkway leading to the memorial.

That directive was based on the September 2022 final report the Department of Defense Naming Commission sent to Congress, which recommended removing names associated with the Confederacy from U.S. military assets. The May 2023 change of Fort Benning’s name to Fort Moore was part of that process.

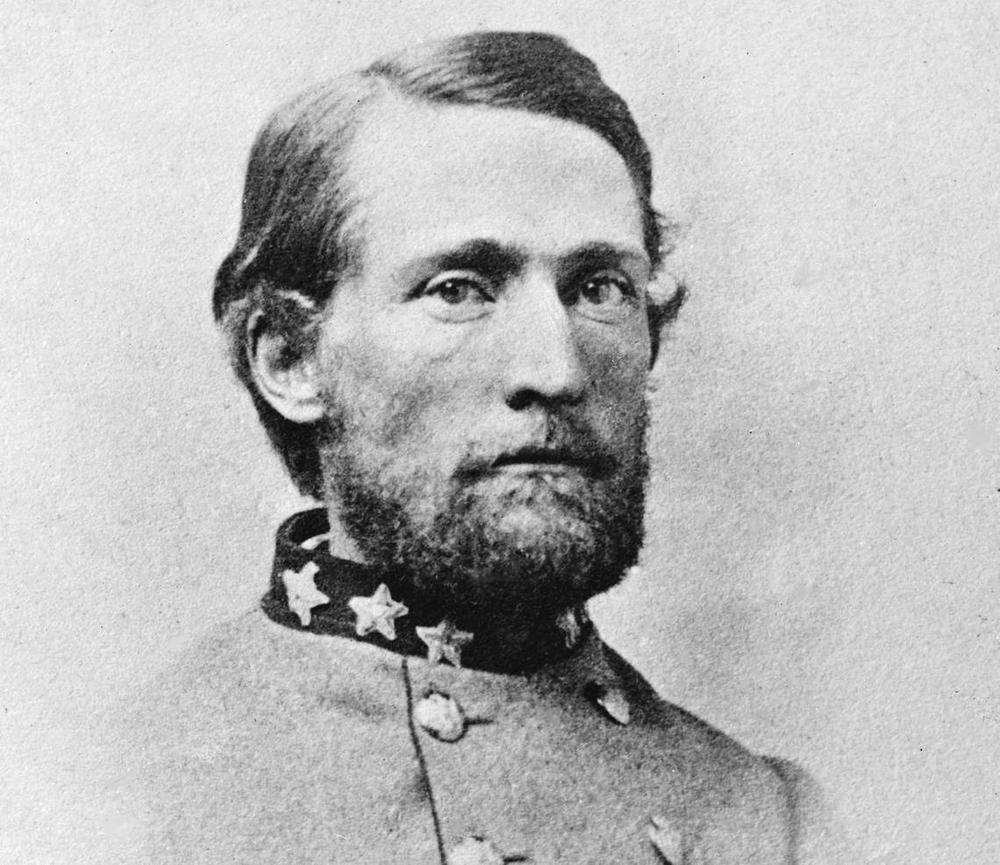

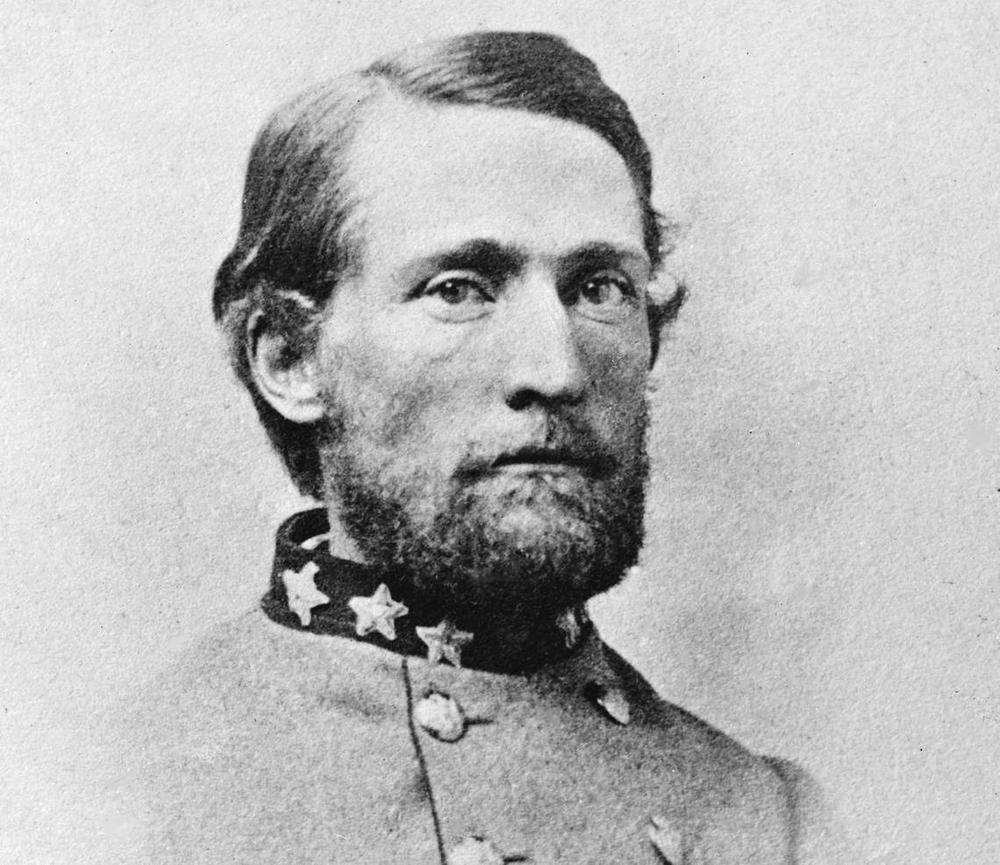

Who was John Mosby?

According to the foundation, Mosby was known as “the Gray Ghost” for his elusive guerrilla tactics during the Civil War.

“One prevalent myth is that Mosby was a staunch Confederate loyalist and a racist,” foundation executive director Blair Brown said in a news release last month. “While Mosby did serve the Confederacy as a cavalry battalion commander, his personal beliefs and actions tell a different story. Mosby was not an ardent defender of the Confederate cause or its principles. In fact, he viewed the Civil War primarily as a struggle for states’ rights rather than a fight to preserve slavery.”

Brown contends that Mosby “harbored abolitionist sentiments. Before the war, he expressed disdain for slavery, considering it morally wrong. After the war, his actions further confirmed his opposition to racial injustice. Mosby aligned himself with the Republican Party, which was unusual for a former Confederate officer, and supported the Reconstruction efforts to ensure the rights of newly freed African Americans.”

Brown argues another false narrative is that Mosby maintained a life of guerrilla warfare or lawlessness after the Civil War.

“In reality, Mosby transitioned into a life of public service and became a dedicated patriot,” Brown said. “He served as the U.S. consul to Hong Kong and worked in various capacities within the federal government.”

Brown calls Mosby’s postwar career “a testament to his commitment to the United States. He sought to heal the nation’s wounds by advocating for reconciliation between the North and South.”

Mosby supported Ulysses S. Grant’s presidential campaigns and worked as an attorney in the U.S. Department of Justice, which “highlighted his dedication to the country’s legal and political systems,” Brown said.

In his personal life, Mosby “was known to have good relations with African Americans and actively worked to protect them during the tumultuous Reconstruction era,” Brown said. “His opposition to the Ku Klux Klan and similar organizations further underscores his stance against racial violence and discrimination.”

Brown concluded, “Colonel John S. Mosby was a man of complex beliefs and actions, far removed from the simplistic and often erroneous portrayals. His opposition to slavery, his efforts towards national reconciliation, and his post-war patriotic service paint a picture of a man dedicated to the ideals of justice and unity.

“Understanding Mosby in this light not only corrects the historical record but also honors his true legacy as an American who strove to bridge the divides of his time.”

Arguments in the case

Jonathan Corley, a lawyer representing the foundation, argued during the Dec. 12 hearing that while Mosby’s name did appear in the body of a report recommending his name be removed from the memorial, it was not included in an appendix of that report, which contained a list of assets recommended to be changed.

That report was compiled by a commission responsible for identifying DOD assets commemorating the Confederacy or those who served voluntarily with the Confederate States of America, according to court arguments.

Land asked Corley whether he was arguing that the inconsistency between the report’s body and the appendix was causing ambiguity. Corley said it was.

Corley argued that the statute required Mosby’s removal from the memorial to be included in the list.

Sarah Suwanda, a lawyer representing the Department of Defense, argued the report is not ambiguous and the statute does not say the appendix is the list.

A document previously submitted by counsel for the defendants, which included the defense’s arguments, claims the DOD defendants acted pursuant to a congressional mandate. That required the removal of any names from DOD assets that commemorated those who voluntarily served in the Confederate States of America.

The document says Part I of the Naming Commission’s final report to Congress recommended the removal of Mosby’s name from display on the Ranger memorial.

The document says Appendix F to Part I doesn’t include the Mosby paver or the inscription on the Ranger Hall of Fame, both of which they claim are located within the Ranger memorial, previously identified as for removal in the body of Part I. However, the name “John S. Mosby” is identified for removal from various DOD assets seven other times, the document says.

Why the judge dismissed the case

In his 24-page ruling, Land concluded, “Mosby’s ranger tactics and methods may be worthy of admiration and respect in some quarters. But other Americans may genuinely conclude that the development and deployment of them as an officer of the Confederate States of America in an open rebellion against the United States adds a treasonous taint that overcomes the appropriateness of any tribute to the effectiveness of some specific maneuver or survival technique.

“It is beyond reasonable dispute that the United States Congress, consisting of the duly elected representatives of the American people, has the authority to decide whether Mosby should be memorialized and honored on a United States military installation. Congress has determined that he should not be, and the Court finds that its determination was properly implemented by the Secretary of Defense. NRMF’s allegations do not state any plausible legal claim upon which relief may be granted.”

Reporter Kelby Hutchison contributed to this article, which comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with the Ledger-Enquirer.