Section Branding

Header Content

As winter storms surge across the country, here's how one homeless shelter is coping

Primary Content

A massive winter storm descended on Washington, D.C., on Monday, dropping some 8 inches of snow on the city while the wind chill dropped to 10 degrees by early Tuesday.

"I don't like the cold, Latin Americans don't like the cold," says Oswill Nazareth Zorrilla Rojas, who says he's been living in a tent for the last three months.

He says he lost his job at a tire shop and his immigration documents were stolen. Now he's been making do in a tent in the heart of the city.

As winter storms and an "Arctic outbreak" swept across the U.S. this week, he was one of the tens of thousands of homeless people surviving the freezing conditions. Homelessness in the U.S. surged by 18% last year and hit record highs, according to a federal report released last month.

With biting winds blowing on Tuesday, NPR visited a D.C. shelter to see how people are handling the conditions.

We were there during lunch, with a steady stream of men flowing in and out. Many of them simply come for meals and leave, while others spend the night. This is a men's shelter with a capacity of 170 beds.

The shelter, Central Union Mission, has been in its current location near D.C.'s Union Station since 2013. The organization goes back to 1884 and says it is the oldest private social service agency in Washington.

"Winter is always going to be a time where we're going to find ourselves at capacity levels," says Ron Stanley Jr., a pastor who serves as the vice president of men's ministry at the Mission.

D.C. is in the middle of a cold emergency, and Central Union Mission is required to take in people who need shelter at the last minute, which means they can't overbook their beds.

With cold like this, "probably more than usual" people are coming through their doors, Stanley says.

But he says it's business as usual for the shelter. "We make sure the building is warm, make sure we have someplace for them to stay, and we make sure that they get something to eat," Stanley says.

A familiar story: Health issues pushed one man into homelessness

Upstairs the mission has classrooms, offices and rooms with bunk beds.

There are 6-month and 16-month programs for helping those in need to "reenter society with better skills," Stanley says. Programs help with financial management and substance abuse. There are offices for a dentist and a doctor.

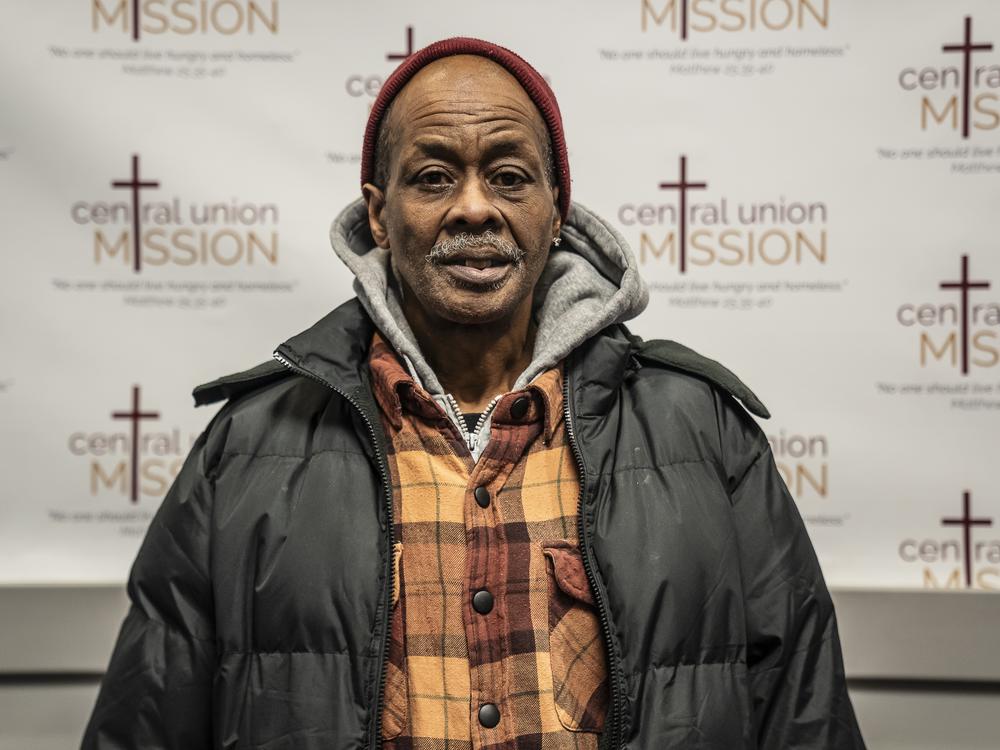

We met Willie Wiggins, who volunteers in the mission's kitchen.

His story has similarities with many Americans: Cancer pushed him into homelessness. He says he had a job setting up meeting rooms and ballrooms at a hotel, but he had surgery for prostate cancer and was out of work for three months. His insurance money wasn't enough to cover things as he fell behind in rent. He says he's been homeless for 18 months.

Wiggins is a big advocate for the shelter and its programs. He says he's been seeing additional people come through because of the weather.

Although many people don't want to go to shelters, Wiggins says "it's the best time now," because of the cold, to tell people they "don't have to go out there again."

Central Union Mission is a place "where they have programs to help renew your mind, help you get you back on your feet," he says. He's a graduate of one of the programs. "People can still graduate and join a program because people such as myself want to give back and talk to them," Wiggins says.

Homelessness happens year-round

Downstairs, men are still coming and going for lunch.

Charles Adams has a clicker and is keeping track of how many people are entering the cafeteria. While he's staying at the shelter, he says he's volunteering his time, hoping to give back. He says he's been without a stable home for 2 1/2 years, a situation caused by drugs. But he says he's now clean. He has a job as a chef at a university.

This is a Christian shelter that emphasizes God in many of its programs. When asked about how the current cold spell has affected him, Adams says he realized earlier: "Cold changed my thinking. Doing drugs is not worth me being out there freezing to death. God didn't intend for me to live like that."

With the current snowstorm, "I start to see more people come out of the woodwork now," he says. Dinner lines will be out the door.

When the weather is nice, he says, that doesn't happen.

Still, homelessness happens year-round. Summers at the shelter are often almost as full as winter, according to Stanley.

Last year's single night tally of homelessness in D.C. counted more than 5,600 people — 14% higher than the previous year, though lower than a count from pre-pandemic 2020.

And nationwide, an annual report last month showed a record number of people living in shelters or outside, with more than 274,000 people sleeping unsheltered. Single-night counts are widely considered to undercount the true number of unhoused people.

The lack of affordable housing is a major factor, advocates say. When rents rise, so does homelessness, according to research by the Pew Charitable Trusts.

The next "point-in-time" count of homelessness in D.C. is happening later this month.

NPR's Manuela López Restrepo contributed translation.