Caption

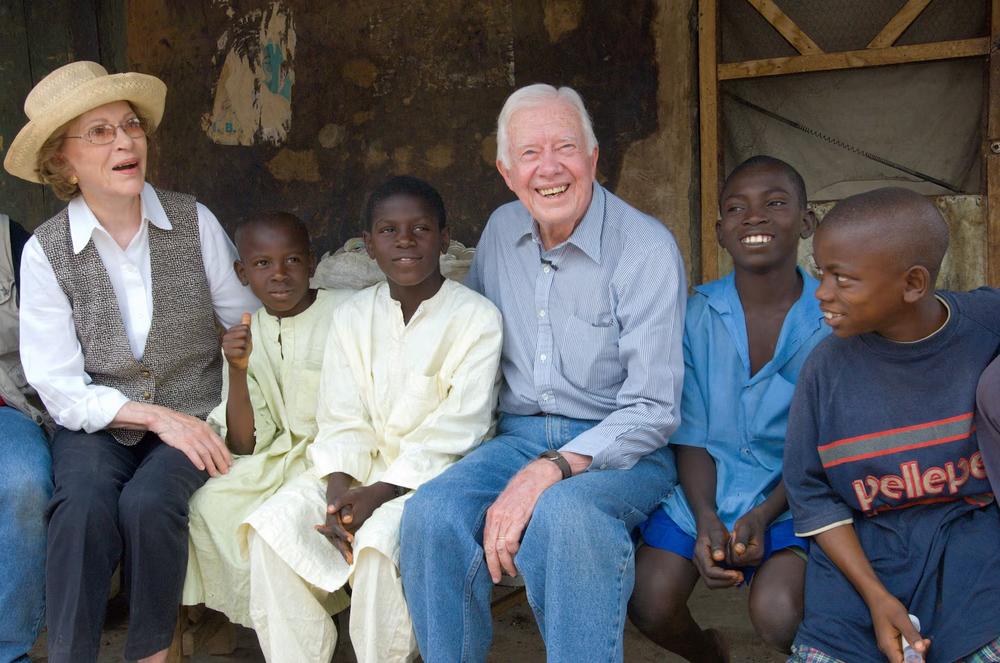

Former President Jimmy Carter comforts 6-year-old Ruhama Issah at Savelugu Hospital as a Carter Center volunteer, Adams Bawa, dresses her extremely painful Guinea worm wound in Savelugu, Ghana, in February 2007.

Credit: The Carter Center