Section Branding

Header Content

Georgia Today: Georgia's bird flu response; Education funding legislation; Sherman's March book

Primary Content

LISTEN: On the Tuesday, Feb. 11 edition of Georgia Today: State officials lift a suspension on poultry sales following a nationwide bird flu outbreak; Georgia democrats look to increase funding for the state's public schools; and a conversation with historian Bennett Parten on how Georgia became home to the largest emancipation event in American history.

Peter Biello: Welcome to the Georgia Today podcast from GPB News. Today is Tuesday, Feb. 11. I'm Peter Biello. This podcast features the latest reports from the GPB news team. Got a suggestion or story tip? Send it to GeorgiaToday@GPB.org. On today's episode: State officials lift a suspension on poultry sales following a nationwide bird flu outbreak. Georgia Democrats look to increase funding for the state's public schools. And we'll have a conversation with historian Bennett Parten on how Georgia became home to the largest emancipation event in American history.

Bennett Parton: And it is a moment that is important for this constant redefining of this idea of American freedom.

Peter Biello: These stories and more are coming up on this edition of Georgia Today.

Story 1:

Peter Biello: The Georgia Department of Agriculture yesterday lifted its suspension on live poultry sales after an outbreak of H5N1 and avian flu. This is the second year for the U.S. of dealing with the virus sometimes called bird flu. Georgia has been able to stay ahead of it until recently. Earlier this month, bird flu caused the shutdown of an operation growing chickens for the dinner table in Elbert County. As GPB reporters Chase McGee and Sofi Gratas explain, that's because the state has a longstanding system for disease prevention and response.

Chase McGee: Old, sun-bleached biosecurity signs warn unauthorized people to stay out of farms on the way to ground zero a few days after the over county outbreak. Closer to the site, back roads leading into the infected chicken houses are blocked — part of the quick response to the outbreak. State veterinarian Janemarie Hennebelle says speed is crucial and humane.

Janemarie Hennebelle: We want to get out there immediately so that we limit suffering of those birds. It is very unpleasant for the chickens that are affected.

Chase McGee: All it takes is one infected chicken for the avian flu to spread and wipe out a whole chicken house. And so, Hennebelle says, any chicken producer with a positive case has to kill their entire flock — cull them all at once. Culled birds can't be sold or eaten, either. In Elbert County, that meant killing over 100,000 chickens over a weekend.

Janemarie Hennebelle: To go through that, to see that on your own farm with your own birds. It's — it's very difficult.

Chase McGee: But Hennebelle says to do otherwise would risk the collapse of a major part of the food system.

Janemarie Hennebelle: What I have to think about from where I'm sitting is I have to think about the entire population of chickens in the state of Georgia, all of our neighbors and across the country. We are trying to protect human health and we are certainly actively protecting the food supply.

Chase McGee: That work takes thousands of people: scientists, policymakers, plus farmers, big and small.

Sofi Gratas: And avian influenza isn't going away. Over the past year, the virus has mutated and spread into previously unimaginable species, including cows, domestic cats and humans. Luckily, officials we talked to in Georgia say they are prepared.

Tyler Harper: And, you know, Georgia's the No. 1 poultry state in the nation. Over 35% of Georgia's ag economy is tied to the poultry industry.

Sofi Gratas: That's Agriculture Commissioner Tyler Harper at the state capitol. Chickens are Georgia's No. 1 farm product and eggs are its second. To protect this industry, chicken farms are expected to use biosecurity: essentially, steps to eliminate virus spread that starts in wild bird populations, explains Alex Turner with the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Alex Turner: Because the virus can pass on trucks, on equipment, on feed, on feet.

Sofi Gratas: It's very transmissible. But:

Tyler Harper: The virus is not a tough one to kill as viruses go.

Sofi Gratas: Chris Scheodel uses Lysol. And she hasn't let anyone near her 16 chickens for about three years. She met me at a feed store, wearing her shoes meant only for errand running.

Chris Scheodel: These are my leaving the house hoes. I have slippers I wear in the house and then boots I wear out to the coop.

Sofi Gratas: She'll disinfect her shoes before driving home. Scheodel says measures like this have worked.

Chris Scheodel: The worst I've had in my flock lately has been just a little injury on a foot.

Sofi Gratas: How long do you think you'll maintain the biosecurity measures that you do?

Chris Scheodel: Probably forever.

Sofi Gratas: All of Scheodel's birds get tested for avian influenza twice a year.

Binu Velayudhan: These are the PCR machines. They amplify...

Chase McGee: Those samples get sent here to the UGA Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory in Athens directed by Binu Velayudhan.

Binu Velayudhan: So we are ready and prepared all the time to rapidly respond to any high-consequence pathogens.

Chase McGee: Another lab test samples from commercial flocks. The labs work with the USDA and receive federal funding for surveillance that lab microbiologist Grazieli Maboni calls critical.

Grazieli Maboni: We know that diagnostics is essential and we need, you know, to invest on that.

Chase McGee: Especially, she says. As scientists warn of the threat H5N1 could pose to human public health. For GPB News, I'm Chase McGee.

Sofi Gratas: And I'm Sofi Gratas.

Story 2:

Peter Biello: Georgia Democrats yesterday announced new legislation aimed at increasing funding for the state's schools. GPB's Sarah Kalis reports.

Sarah Kallis: State Sen. Jason Estevez, a former schoolteacher, says it's time to revisit Georgia's public school funding formula, which dates back to 1985. And some critics say it underfunds public schools.

Jason Estevez: Teachers and districts in low-income communities across the state face unique challenges, and we must provide additional resources through a poverty weight or an opportunity grant.

Sarah Kallis: Estevez says his bill, Senate Bill 128, would steer about $2 billion in funding to low-income schools around the state. While the state's funding formula was originally designed to balance funding between wealthy and poorer districts, some critics say that balance has eroded over time. For GPB News, I'm Sarah Kallis at the state capitol.

Story 3:

Peter Biello: Georgia lawmakers are considering a bill that would allow the state's pension fund to take on more risk in hopes of higher returns. Senate Bill 23 would raise the cap on how much the employees' retirement system of Georgia can invest in alternative investments, things like private equity and hedge funds. Right now, the limit is 5%. The bill would double that to 10%. Opponents like Democrat David Lucas of Macon worry it could be risky.

David Lucas: What happens if they take the money and when they invest and the folks belly up, who's gonna have to pay the difference then?

Peter Biello: Supporters say it could boost returns and strengthen the pension fund's long-term health.

Story 4:

Peter Biello: A Georgia state House member won't face a new election after all. A judge ruled yesterday there was not enough evidence to prove voters who received wrong ballots swayed the election's outcome. That means Democratic incumbent Mac Jackson will stay in office. He beat Republican challenger Tracy Wheeler by 48 votes out of more than 27,000 votes cast in November. Wheeler sued to seek a new election, arguing that some people got ballots for the wrong district. The judge says Wheeler failed to meet the high bar for overturning an election. Wheeler says she may appeal.

Story 5:

Peter Biello: Legislation backed by Gov. Brian Kemp aimed at limiting jury awards in civil suits cleared a state Senate committee after a five-hour hearing last night. The Republican majority Senate Judiciary Committee voted 8 to 3 along party lines to advance the measure to the full Senate for consideration. John Triplett, a grocer from Southeast Georgia's Screven County, told the panel large jury awards are driving up business costs.

John Triplett: Insurance premiums have gone up, hours have gone up. The future of the grocery industry is at stake if something doesn't change because of the tight margins.

Peter Biello: Opponents, including trial lawyers, argue the bill will further enrich insurance companies and harm accident victims without reducing insurance premiums.

Story 6:

Peter Biello: Former Georgia Sen. Sam Nunn is warning people about the potential dangers of artificial intelligence. Nunn spoke last week at an annual national security forum at the Museum of Aviation in Warner Robins. He said AI has great potential to improve humankind. It needs to be guided by human values and decision-making.

Sam Nunn: The bottom line is you're going to have to be in the loop. Humanity is going to have to be in the loop if we're going to enjoy the huge benefit of — the huge benefits of the innovative technology and avoid the dark side risk — at least mitigate those. Humans must give shape and purpose to our technologies and breathe heart, breathe soul, breathe values and breathed wisdom into our science and technology.

Peter Biello: Nunn is now affiliated with the nonprofit Nuclear Threat Initiative. He represented Georgia in the U.S. Senate for 25 years, ending in 1997, chairing the powerful Armed Services Committee.

Story 7:

Peter Biello: Coca-Cola's CEO says he doesn't think the Trump administration's new tariffs on aluminum will have much of an impact on his company's bottom line. CEO James Quincey told investors this morning that the Atlanta-based beverage giant can adapt to the tariffs in part by shifting to plastic bottles.

James Quincey: If aluminum cans become more expensive, we can put more emphasis on PET bottles. So we will adapt the packaging strategy in function of changes in the relative input costs of what goes into that.

Peter Biello: He said the 25% tariff on aluminum is not insignificant, but also not going to, quote, "radically change a multibillion-dollar business." Coca-Cola posted better-than-expected revenue in the fourth quarter as sales volumes rose in the U.S., China and elsewhere.

Story 8:

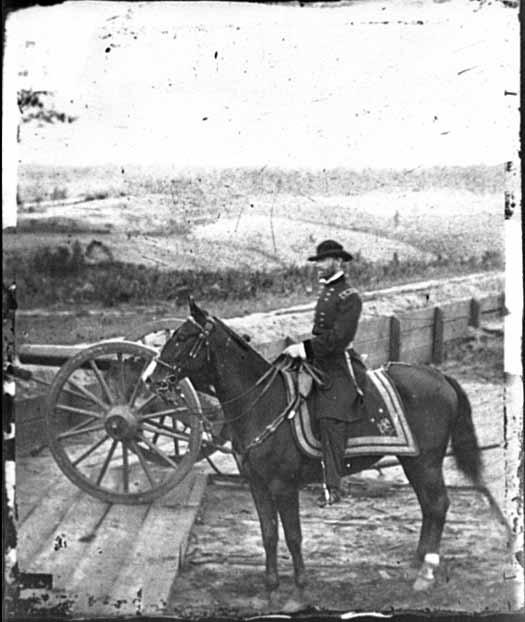

Peter Biello: Perhaps the most widely known impact of Gen. William Sherman's march to Savannah in the fall of 1864 is the near-complete destruction of Atlanta. A huge portion of the city was burned as the Union Army delivered one of the final blows to the Confederacy. But Sherman's march did more than that. As Union soldiers marched to Savannah. Enslaved people joined them. When the army arrived in Savannah, thousands of people struggle to survive in an unfamiliar place without connections or resources. In his new book, historian Bennett Parten looks deeply into this lesser-known story. It's called Somewhere Toward Freedom: Sherman's March and the Story of America's Largest Emancipation. Bennett Parton, welcome to the program.

Bennett Parton: Thanks for having me.

Peter Biello: So what you're writing about happened after the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. But even before that, the U.S. government and the U.S. Army were trying to figure out the legal status of enslaved people who fled to the Union Army. This was ultimately how enslaved people knew that they could join the Army or be with the Army to ensure their safety to some extent. But what were they considered legally at that point?

Bennett Parten: The policies of emancipation in the Civil War is a real evolving story. It begins in 1861 with a law known as the First Confiscation Act, which treats enslaved people as confiscated property. However, the distinction there is that only enslaved people who claim to have been forced to work for the Confederacy in some capacity were given refuge within the Army's lines. After that, about a year later, more and more enslaved people continue to flee to the Army. This becomes a problem for the Army and also the U.S. government. Congress passes a humdrum bill known as the Second Confiscation Act, which is essentially an emancipation declaration. It is Congress's way of saying the enslaved people who come to Army lines are considered thenceforth and forever free. So there is an evolution in emancipation policy from one that treats enslaved people as requisitioned property, requisitioned from the Confederacy as "contraband of war" — that's often the term that's used — to one that recognizes them as free individuals.

Peter Biello: So this book deals largely with the march from Atlanta to Savannah. What you write about here is essentially that on the way, enslaved people whose "owners" have been displaced, maybe their plantations have been burned, they join the Army along the way, and it becomes a caravan of people led by the Army. What was that like for those people following along?

Bennett Parten: It was a harrowing experience for a lot of folks. It was one that was deeply complicated. Some of Sherman's soldiers and some of his subordinates — you know, the officers of rank — were quite willing to allow enslaved people to join the Army and to follow them. But there were equal numbers of soldiers and subordinates of Sherman's that were not as welcoming. And so it could really vary, this refugee experience or this experience with emancipation. And this is important because I think that is how most historians now see the experience of emancipation more broadly, which is that it was quite literally, for many, a true refugee experience. It's one that's defined by uncertainty, a lack of security, a lack of stability. This is well before any sort of legal refugee status is in place or any conversations about citizenship status. And so it was a real liminal experience of sort that was defined by deep uncertainty and complexity. And I think that the experience of Sherman's march is really a kind of symbolic reflection of the emancipation experience more broadly. I should say Sherman expected the enslaved people to follow him [or] at least run to the Army. And in fact, as part of his official campaign orders, he says that enslaved people who run to his Army may be taken along so long as they are able-bodied and able to fend for themselves or help the Army. But that it was the soldier's first responsibility to see to their own well-being and the well-being of their troops.

Peter Biello: And as you write here, you know, there's something of a symbiotic relationship with those who followed along in the sense that they were able to point Union troops in the right direction when they were plundering the abandoned plantations. Union soldiers also were providing some protection from Confederate troops who were still scouring the countryside in search of enslaved people who may have gotten away.

Bennett Parten: Yeah, I mean, one of the things that surprised me the most in writing this book was just how present enslaved people were at every step of the march. And it wasn't just the fact that they were present. It's that they were active agents and active participants in the Army's movements. They acted as scouts, as spies, as intelligence agents. They pointed the way down hidden footpaths. They were able to offer information about where the Confederate calvary was.

Peter Biello: So when Sherman's army arrives in Savannah, it is not burned the way Atlanta was burned, in part because the local government there ingratiated themselves to Sherman in an attempt to preserve the structures of the city. And the formerly enslaved people who've been following the Army, they kind of — correct me if I'm wrong here — for the most part, stayed outside the city limits and eventually were settled on various sea islands, correct?

Bennett Parten: That's right, yeah. By the time that Sherman arrives on the Ogeechee, which in the advance into Savannah, it's the Ogeechee River, south of Savannah — which is one of those classic intercoastal waterways — that becomes the main waterway for the Army because it connects Sherman to the Atlantic Ocean. By the time he arrives there, at a place called Kingsbridge, which is a former bridge that had been burned that he uses as a depot on the Ogeechee, he sets in motion this real elaborate movement of the refugees down the Ogeechee around Savannah, around the Daufuskie Island, around Hilton Head in the Port Royal Sound, to begin settling them on the islands around Port Royal [and] Buford — this is the South Carolina Sea Islands. And the reason he does that is because at Port Royal, and around Port Royal, the town of Buford, there is an ongoing freedman's colony known as the Port Royal Experiment.

Peter Biello: Yeah, the Port Royal Experiment was an opportunity for formerly enslaved people to work land and profit from their work. And there were other attempts after Sherman's march to give land to formerly enslaved people. But those didn't work out as many had hoped. And you go into detail about that in your book. But overall, Bennett Parten, what would you say is the legacy of Sherman's march?

Bennett Parten: One of the real legacies of the march and one of things that I try to argue in this book is that while we have long known the march as a military event, really the best way to understand it is as a freedom movement. And I think we should also recognize the march as being one of these moments in American history where what American freedom means is really on the table. And it is a moment that is important for this constant redefining of this idea of American freedom. And I say that because when enslaved people ran to the Army, they were consistently imagining what freedom might mean for them. And in their conversations with the soldiers, they were explaining to them the reasons why they decided to drop everything and follow the Army and what they hoped to achieve in arriving in Savannah or elsewhere. And so, like a Selma, Ala., like a Philadelphia in 1776, like at Gettysburg or Yorktown, it's one of these moments that has had real, I think, consequences for what American freedom actually means. And it's one of these moments where American freedom is being debated and acted upon in real time.

Peter Biello: Well, the book is Somewhere Toward Freedom: Sherman's March and the Story of America's Largest Emancipation. Bennett Parten, thank you. And Bennett Parten and will be speaking about his book tomorrow night at 7:00 at the Atlanta History Center. And Parten's book is the subject of the latest episode of Narrative Edge, GPB's podcast about books with Georgia connections hosted by me and Orlando Montoya. You can find that at GPB.org/NarrativeEdge or wherever you get your podcasts.

Peter Biello: And that's all the news fit to podcast today. Thank you so much for tuning in and we're going to be back tomorrow. We hope you will join us. Make sure you subscribe to this podcast and check GPB.org/news for any updates. And again, if you've got some feedback, the best way to reach us is by email. The address is GeorgiaToday@GPB.org. I'm Peter Biello. Thanks again for listening. We'll see you tomorrow.

---

For more on these stories and more, go to GPB.org/news