Caption

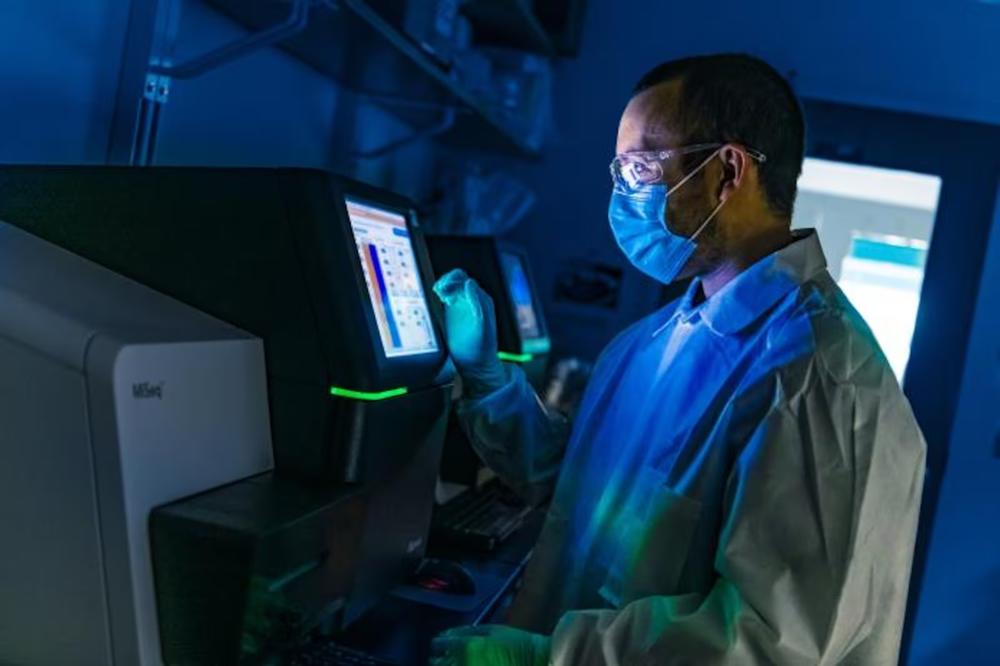

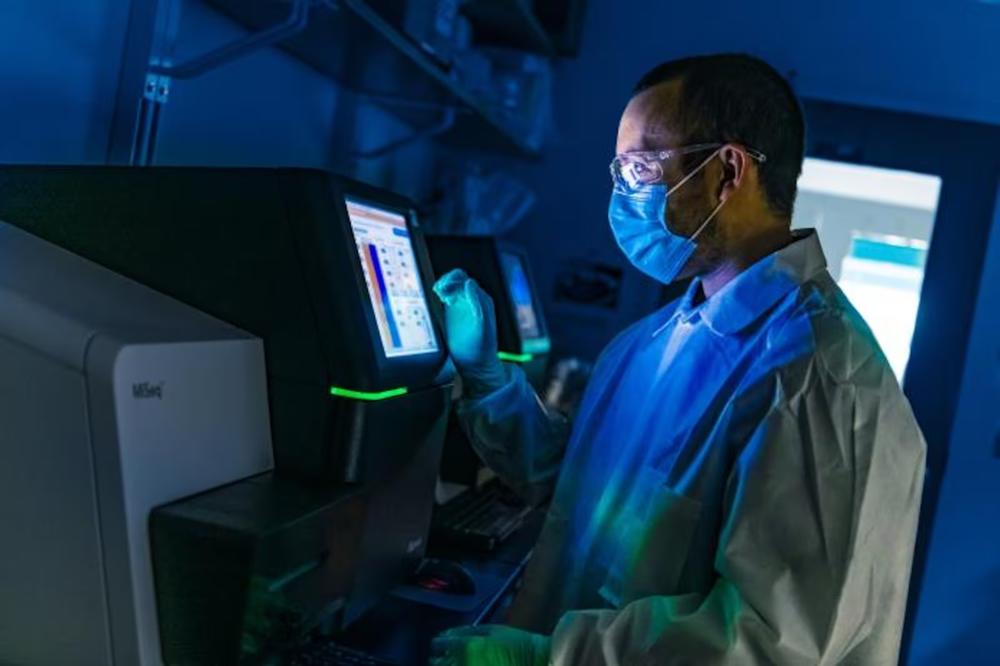

Georgia received over $780 million in National Institutes of Health research grants in fiscal 2024.

Credit: Lauren Bishop / CDC

Georgia received over $780 million in National Institutes of Health research grants in fiscal 2024.

Georgia’s statewide public health conference has been canceled, and researchers are navigating disruptions in federal data accessibility and funding, with Emory University President Gregory Fenves in Washington this week to meet with lawmakers.

Georgia received over $780 million in National Institutes of Health research grants in fiscal 2024. About $488 million of that went to Emory. Other top Georgia recipients include the University of Georgia, Augusta University, Georgia Tech, Georgia State University and Morehouse School of Medicine.

A new NIH policy ordered by the Trump administration would reduce the amount grants pay to universities to help with the costs of conducting research – items like facilities and administrative support.

That reduction would cost Emory about $140 million a year, according to a Saturday email to faculty and staff from Ravi Thadhani, executive vice president for health affairs, and Lanny Liebeskind, interim provost and vice president for academic affairs.

A federal judge on Monday temporarily blocked the guidance from taking effect in response to lawsuits, including one filed by the American Council on Education and a group of research universities and other national organizations.

A separate lawsuit filed by 22 attorneys general succeeded in getting the guidance temporarily blocked in those states. Georgia is not among them.

Still, Emory leaders are worried.

“The university depends on federal funding to power many important initiatives …. Now, elements of that partnership are evolving, and it will be challenging for the entire university,” Fenves wrote Tuesday in a note to “the Emory community.”

Fenves was in Washington, D.C., on Tuesday to meet with elected officials.

“It is our responsibility to make a compelling case for the value of Emory’s research and scholarship as part of a national research enterprise that has propelled economic growth, health and well-being, workforce development, and international competitiveness in the United States,” he said in the statement.

NIH projects in Georgia encompass a wide range of basic and applied research, including new treatments for lung cancer, stroke rehabilitation, alcohol and substance use disorders, and many other fields.

The threat of federal funding cuts has created a “context of profound uncertainty” for faculty and students at Georgia State University, said Harry Heiman, a professor of public health.

Students have also lost access to key datasets, interrupting research, Heiman said.

For example, HIV data on the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website had been removed.

“They’re not sure what to do all of a sudden,” Heiman said. “The data that they’ve been using to try to better understand and help solve critical public health problems … that work is put on hold as is their training, which they’ve invested significant time, energy and dollars in getting.”

The data removals started after Jan. 20 executive orders from President Donald Trump banning Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion initiatives, allowing the recognition of only two genders, and banning federal funding for “gender ideology.”

A federal judge issued a temporary restraining order Tuesday ordering the agencies to restore the missing data after nonprofit group Doctors for America sued over the removals.

The nation’s largest public health surveillance system, the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, was taken offline. It was restored, but some data were still missing Wednesday, including a data explorer tool.

Its website, like many others at the CDC, displays a banner saying the “CDC’s website is being modified to comply with President Trump’s Executive Orders.”

Emory Professor Nadine Kaslow said the survey “provides without a doubt the best information we have in our country” about high school students’ mental and behavioral health.

It includes data on a wide range of social identities, behaviors such as social media interactions, and even protective factors that can help young people cope with adversity.

Kaslow said states do and should collect data, but the national view from the survey is important for federal policymaking.

“It also allows us to learn from other states who implement programs,” she said.

The Georgia Department of Public Health and the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities use the survey data to track youth behavior and guide policy, Kaslow said.

“I am extremely concerned that having less access to existing data … will reduce our ability to understand young people in this country,” she said.

Meanwhile, a pause on non-essential travel at the state DPH has prompted the state public health association to cancel its annual conference.

Scheduled for April 30 to May 2 on Jekyll Island, the event has been canceled due to “the current pause in federal funding and due to directives received from the Georgia Department of Public Health,” according to a Friday email from Valerie Melson, an executive assistant at the District 4 public health district in LaGrange.

DPH’s travel freeze would have prevented most of the over 600 expected attendees from coming, GPHA President Dr. Jimmie Smith said. Most of the attendees work for county, district, and state public health programs.

“It wasn’t a decision we made lightly, but [we] had to look at all the factors that surrounded it,” Smith said of the cancellation.

The conference gives frontline public health workers, researchers, and board of health members from across the state a chance to get together and learn from each other, said Jack Bernard, a longtime attendee who is chairperson of the Fayette County Board of Health.

County health board members like Bernard are usually not trained public health professionals, he said. The conference is a way for them to learn “what our local and state health problems are and the most cost-effective ways of addressing them.”

About half of DPH’s budget comes from the federal government.

The agency paused non-essential travel, defined as non-emergency and non-regulatory travel, as of Feb. 3, spokesperson Nancy Nydam said.

“The travel deferment is not in response to any specific order or direction,” Nydam said. “Because of the continuing uncertainties around federal funding, DPH is being judicious with its discretionary spending to ensure the Department remains on solid financial footing.”

Nydam said funding is currently operating normally and the agency has not experienced delays with reimbursements.

“All routine public health services are continuing as normal,” she said. “At this time personnel are not affected, and it would be premature to speculate about potential changes.”

Rebecca Grapevine is a reporter covering public health in Atlanta for Healthbeat. Contact Rebecca at rgrapevine@healthbeat.org. This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with Healthbeat.