Caption

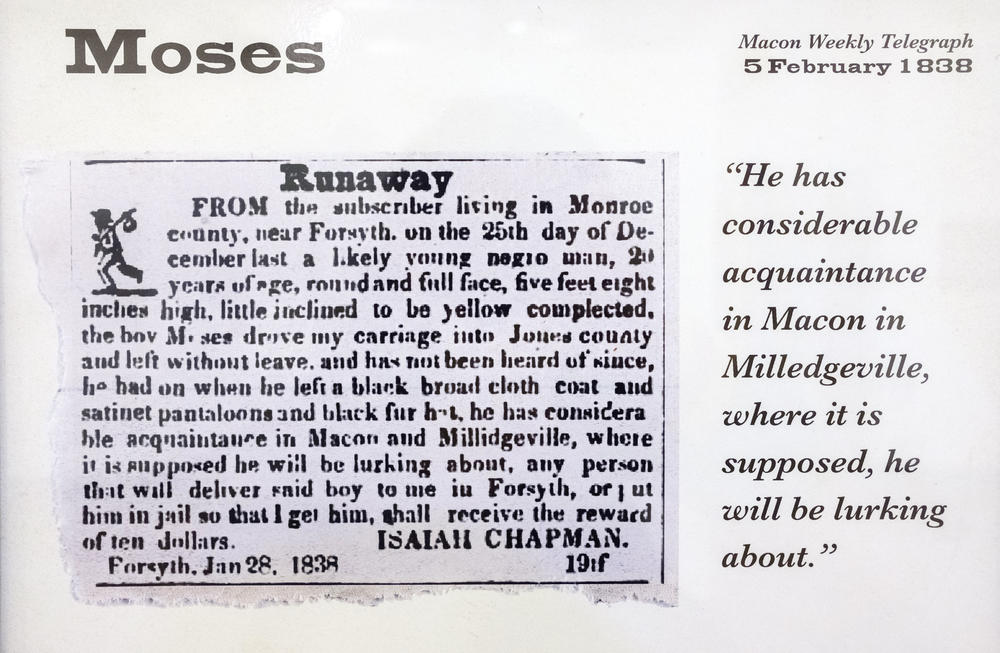

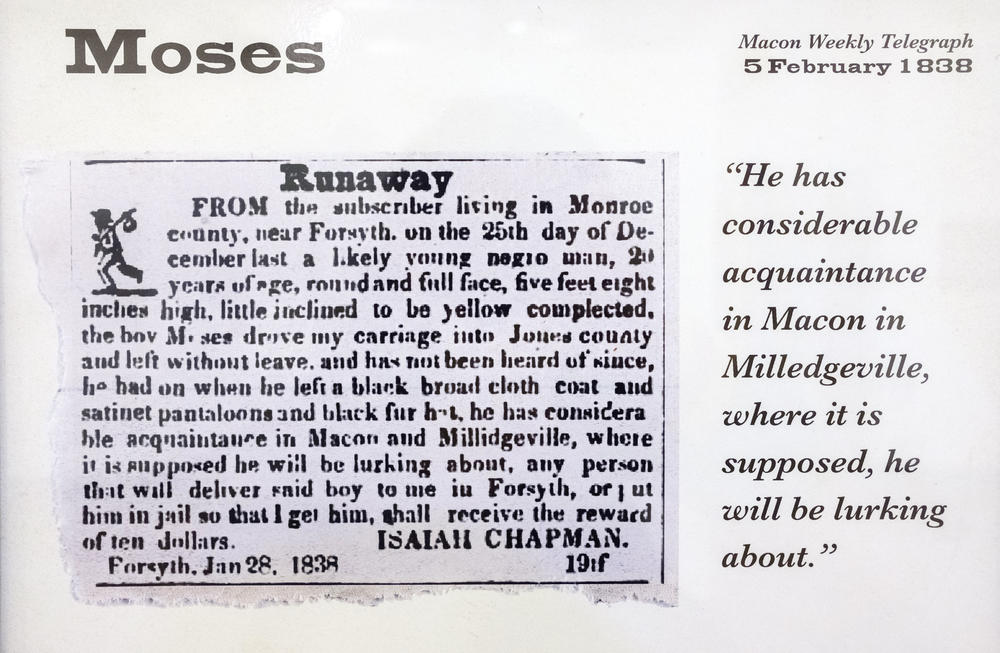

A newspaper ad placed for Moses, an enslaved man who escaped from his enslaver on Christmas Day, is among about two dozen on display in the Tubman African American Museum in Macon, Ga.

Credit: Grant Blankenship/GPB News

LISTEN: When enslaved people fled bondage in the 19th-century South, their enslavers were often forced to describe the people they considered property as human beings in "runaway slave ads" in newspapers. A Macon museum's exhibition shines light on this history. GPB's Grant Blankenship has more.

A newspaper ad placed for Moses, an enslaved man who escaped from his enslaver on Christmas Day, is among about two dozen on display in the Tubman African American Museum in Macon, Ga.

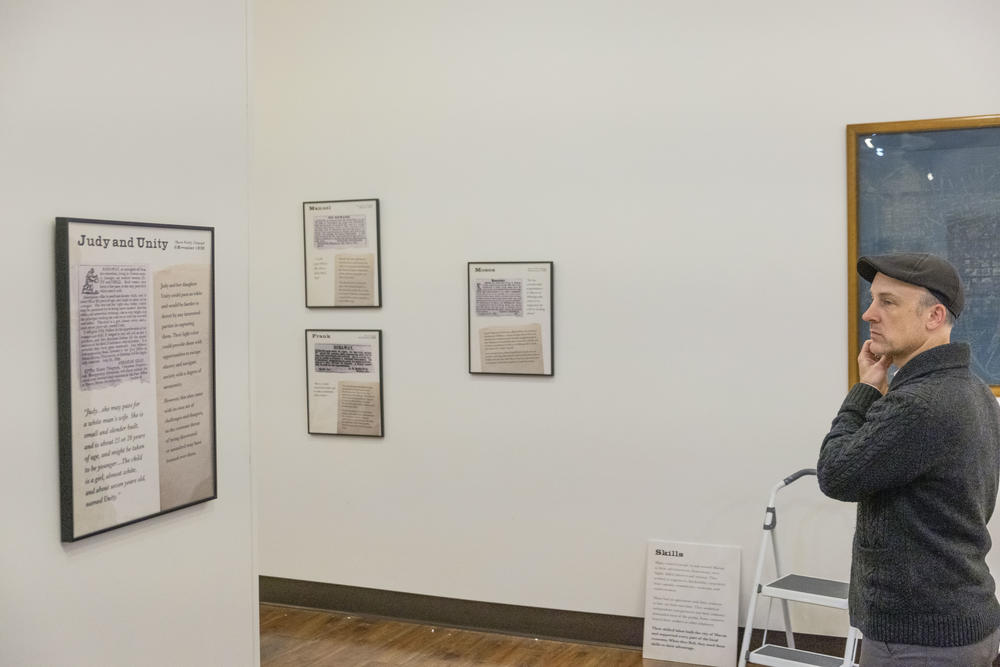

On a recent weekday near the end of January, Jeff Bruce, curator at Macon’s Tubman African American Museum and Matt Harper, professor of Africana Studies at Mercer University, put down their hammers for a quick debate.

“Are you worried about crowding?” Harper asked. “We've got — we've got 18 ads on this wall.”

“Well, that’s the bulk of what we have,” Bruce responded, as he and Harper prepared to mount two dozen newspaper ads from the mid-1800s on the expanse of white space in the narrow, second-floor gallery of the Tubman.

The ads, part of an exhibition called "Freedom Seekers," running until March 22, weren’t for goods or services, but solicitations placed by enslavers trying to recover the people they considered their property.

Printed at the top of each framed ad was the name of the person who fled: Ann. Sandy. Moses.

Details such as the simple facts of individual names are easy to lose in the magnitude of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade: Some 9 million people were trafficked across 35,000 voyages.

Harper said that, in addition to names, enslavers often ignored other things that made the enslaved human, too — that is, until an enslaved person fled. Then, facts had to be acknowledged and published in so-called “runaway slave ads” like the ones in the museum gallery.

"They're writing about people as property,” Harper said.

But enslavers couldn’t stop there.

“They can't help, if they actually want to get these people back, to describe them as people, right?"

Mercer University professor of history and Africana studies Matt Harper after mounting a 19th-century ad asking people look out for Judy and her daughter Unity who'd escaped slavery together. Harper taught the class which researched the ads now being shown at Macon’s Tubman Museum.

The Tubman exhibit invites visitors to see how the ads offer glimpses into the individual lives of the enslaved.

Each of the ads appeared in the Macon Telegraph, which is still in operation today, between 1826 and the end of the Civil War. The names on the ads are almost without exception simply first names.

Harper pointed out one of those exceptions.

“The owner will only call him Tom, but he says he goes by Tom Hammons," Harper said paraphrasing the advertisement text.

"He's not going to give him his last name,” Harper said.

But if someone is trying to find a person, it helps to tell other people exactly who they’re looking for.

When Tom Hammons, a boat hand on the Ocmulgee River, made his escape, he took control of his name by forcing the man he ran from to share it in full, with the larger world.

Harper said it’s the kind of detail he hoped his students would encounter when they began researching so-called runaway slave ads last year.

“This is who they are," Harper said of the ads' descriptions of escapees. "This is who their family members are. These are the things they like to do. This is what they're good at. This is how you'll know them. This is how you distinguish this one from that, this person from that person.

"Their loves, their talents come through."

One named Isaac was described as a good carpenter, fleeing on a sorrel mare in his blue satinet round coat.

Bill was a wagoner on the road between Augusta and Macon who took with him a season’s earnings.

Jim is described as missing a finger and likely on the way to his mother.

Judy and her daughter Unity escaped together, with the mother's right arm said to be disfigured from being broken and the child described as “almost white” by the man seeking them both.

Later, in the gallery, some of Harper’s students came and helped. Simone Walker and Taylor Boyd mounted the panels for the most famous people to escape slavery and Macon: Ellen and William Craft.

Boyd said the details in the ads imbue the enslaved people with humanity.

“They had everyday problems just like us," Boyd said. "Reading their stories and reading that they were running away to families, or they had lovers, that really just exemplifies the importance of why we need to showcase this.”

The ads were common in newspapers across the early colonies, North and South.

An 1764 ad from the New York Mercury asks for help finding Jack, described as about 5 feet, 8 inches tall with a face pitted by smallpox.

“His hair [is] pretty long and [he] stares very much; was born at Hackensack; when he talks, he speaks very quick. He had on when he went away, a short scarlet Duffil Waistcoat, made without flaps,” the enslaver goes on to say before concluding with a warning.

"All Persons are forbid to harbour him, as they shall answer it at their peril.”

By 1850, the federal Fugitive Slave Act had made it unlawful nationally to offer sanctuary to someone fleeing enslavement. And by that time, the ads were mostly a phenomenon of Southern cities.

Not only were the ads threats to anyone who might render escapees aid because of the slave act, they also gave people the opportunity to make money as a bounty hunter — starting with a browse through the ads, which, as graphic design student Naluchi Okonkwo found, included a consistent look.

“It's essentially an icon," Okonkwo said.

Or a set of icons.

“I found a lot of them were repeating. You see it's essentially the same exact graphic of the person walking with the stick.”

That was for men. Ads for women show them running with a bindle. Okonkwo said the icons helped cut through the other visual clutter, like ads for lost oxen or a plantation for sale.

“That way these ....slave catchers, if you will, for lack of a better term, know that you're looking for a man in this time or you're looking for a woman,” Okonkwo said. “Or you're looking for a man and a woman or you're looking for an older man or you're looking for a more spritely man or any of those things.”

It seems unlikely the icons would have worked as visual shorthand if people weren’t seeing them all the time, the way we see brand iconography like Apple’s logo, and Nike swooshes and Facebook’s lowercase blue letter "f" today.

“That shows how prevalent slavery was," Okonkwo said.

The iconography of runaway slave ads was consistent from newspaper to newspaper and from town to town.

Harper said the visual evidence of that prevalence got his students’ attention.

"Students were really surprised by how frequent the ads were, that they were on every single issue, multiple ads per issue,” Harper said. "Some were surprised about how long someone might be looking for someone for two years, three years. Keep running the ads, over and over again, in the paper.”

That definitely struck Tamaya Morrison.

“There were just so many,” Morrison said.

Even a couple months after the class, she still finds herself thinking about the ads.

“Definitely — because my family is from Macon,” she said. “I think this class has really put a lot into perspective as far as, not only my Macon heritage, but like my Southern Black heritage in general. This is how I got here. And it makes so many things make sense."

And in all the ads, there’s one she found particularly ironic.

"The one that sticks out to me the most is the one about Moses, because his name is Moses, of course,” she said.

Even to slaveholding Christians, of which there were many, the biblical figure Moses was known for leading his people from slavery.

“How can you hold a slave named Moses?” Morrison asked. “But, I mean, he still manages to escape and gain his freedom on Christmas Day."

Yes, many of the ads depict suffering, even as the subjects they sought attempted, and often succeeded, in leaving suffering behind, Morrison acknowledged.

“Even through the suffering, you're able to see the resilience of the people,” she said.

The Freedom Seekers exhibit at Macon’s Tubman African American Museum goes through March 22.