Section Branding

Header Content

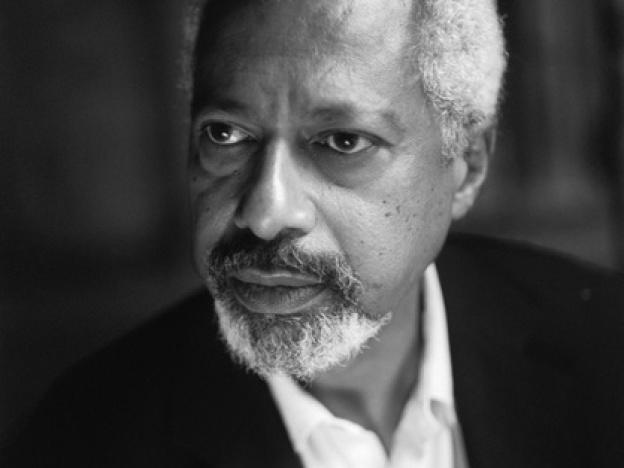

'Everyday, ordinary' things drive Nobel Prize-winning author's new novel 'Theft'

Primary Content

The novelist Abdulrazak Gurnah was about a quarter into his new book when he got the call – he'd won the 2021 Nobel Prize in Literature. Which was great, sure. But all the attention meant he had to take a break from writing that book.

"I couldn't go back to it. I don't like to work under that kind of pressure," Gurnah said.

He eventually returned to those unfinished pages and found there was still some life to them, that there was still a novel here that needed to be written. That book, out Tuesday, is titled Theft. And it showcases the smaller, more intimate side of Gurnah's writing.

The novel takes place in Tanzania, in the '90s, in a moment of rapid change. The government had recently changed its foreign exchange laws, and so tourists are flocking to Zanzibar – its island just off the coast of East Africa. Gurnah, who was born there, said the big money of tourism brought with it new hotels, new people, NGOs. But the influx of tourists also brought "many corruptions," he said. Some beaches and restaurants became exclusively for tourists – no locals allowed. People also began selling tall tales to tourists, to please them.

"You see these guides going around saying 'Freddie Mercury lives there!' This is all lies. You do whatever these people want to hear," he said.

This is where and where the three central characters in Theft find themselves. There's the educated and kind of arrogant Karim. His young wife, Fauzia, who suffers from epilepsy. And Badar, a young servant whom the other two treat almost like a younger sibling. They all come from different worlds, and yet they have something in common. Rightfully or wrongfully, they all feel unwanted by their parents in some way.

"Nobody wants him."

Gurnah suspects this is something a lot of children feel, especially in adolescence. Some grow out of it, realizing that it isn't true. "But in some cases, of course, it's also that they're not wanted," he said. "Like in the case of Badar. Nobody wants him."

People say this to Badar, repeatedly. Early on in the book, the woman who takes Badar in as a boy tells him the story of how his mom died when he was a baby. And how his father up and left. Gurnah writes:

"He was six years old when she first told him that story, and after that she told it to him more than once, without adding anything to it. He cried every time she told it. He felt so dirty. She tutted at him when he cried and wiped his tears with her fingers, but then later she would tell him again. We did the best we could for you, and God will reward us."

Badar does eventually find some footing, some stability in his life. But that gets rocked when he's falsely accused of stealing. This was inspired by something Gurnah saw happen to a kid in town, growing up. "Ideas for novels have a way of hanging around for donkey's years," he said. "I'm so very interested in how people who are apparently powerless save themselves. How it is that they somehow hang on and find a way to get themselves to the other side as well."

Gurnah's last book, Afterlives, was a grand, multi-generational, statement-making novel about colonialism and violence and war. The kind of novel you'd expect from an author with the biggest literary prize to his name. In comparison, the story he tells in Theft is smaller. Or maybe intimate is the better word. The high drama moments happen in plain settings – quiet living rooms, or at the front desk of the hotel where Badar ends up working.

"I like the fact that these are not heroic lives," Gurnah said. "They're also not heroic obstacles. They are regular, everyday, ordinary sort of things."

It's a story about people getting jobs, helping a buddy find a place to stay, and figuring out their place in the world. Not to disagree with the Nobel-prize winner, but the way Gurnah writes it, it all comes off as pretty heroic.