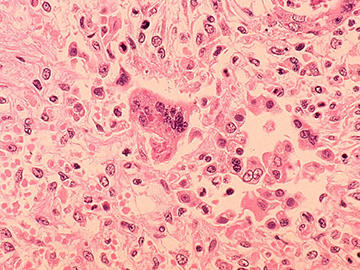

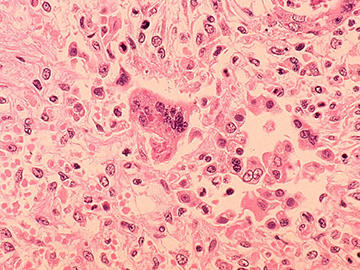

Caption

In 2024, the Georgia Department of Public Health reported six measles cases. In January, Georgia's first new measles case of 2025 has now spread to two family members.

Credit: GPB / File

|Updated: April 10, 2025 3:18 PM

In 2024, the Georgia Department of Public Health reported six measles cases. In January, Georgia's first new measles case of 2025 has now spread to two family members.

At a Tuesday meeting of the Board of the Georgia Department of Public Health, officials discussed who should consider getting a booster of the vaccine that protects against measles, mumps and rubella, or MMR.

That’s against the backgdrop of a major outbreak of measles centered in west Texas, that has infected over 500 people there, with cases also reported in New Mexico and Kansas. The vast majority of cases are in unvaccinated people.

Two children and one adult have died as part of that outbreak, though by Wednesday the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had not updated its count.

Georgia’s State Epidemiologist Cherie Drenzek said there are three groups that she calls “under-vaccinated” and could be at a higher risk of catching measles: adults who have only received one dose of the MMR vaccine, children from 1 to 4 years old due for a second dose, and infants between 6 and 11 months old.

Normally, it’s encouraged that kids get one dose of the MMR at around 1 year of age, and a second dose between four and six years old, in accordance with a routine vaccination schedule.

The DPH now recommends families consider talking to their health care provider about an early vaccine for young kids and infants, or an additional vaccine for adults with only one on record, especially if families plan to travel to areas where measles is active or live in the metro Atlanta area.

“We wouldn't need to go to this sort of recommendation unless you're really dealing with a big outbreak,” Drenzek said.

Following these recommendations can help protect vulnerable people, including those who can’t get the vaccine because of age or other health conditions, and ensure some level of community immunity.

Georgia had one of the first reported cases of measles in the U.S. this year, though unrelated to the outbreak in Texas. Three family members living in metro Atlanta, all unvaccinated, had contracted measles after international travel in January.

Drenzek said the Department conducted comprehensive surveillance of the family and people they had come in contact with, monitoring their symptoms daily. According to open records, DPH closely monitored 45 people.

Since then, there have been no new reported cases of measles in Georgia.

A factsheet from the Georgia Department of Public Health outlines steps in identifying and reporting measles cases.

Most children in the U.S. are fully vaccinated against measles, with a national coverage rate of around 90%. Adults born before 1957 are largely considered to have contracted immunity to the viral disease from prior infection, while those born after should have received at least one shot.

Outbreaks today largely stem from within communities with extremely low vaccination rates. The updated recommendations simply represent a “common sense” approach by the department, Drenzek said.

“If we're thinking about having a widespread measles outbreak across the nation, I think that is actually very unlikely,” Drenzek said.

However, infectious disease experts are warning that if vaccination rates got low enough, as some trends indicate, that risk of a widespread outbreak would be much higher.

DPH is encouraging health care providers to pay close attention to patients who present measles-related symptoms — as is the CDC, which sent out some updated guidance on Tuesday.

Coughing, conjunctivitis and coryza — or the “three C’s” — can be an early indicator of infection. Providers can call the DPH disease reporting tip line, which is staffed 24/7 by an epidemiologist, if they have a suspected case.

So far, DPH has followed up on a couple dozen cases “out of an abundance of caution,” Drenzek said.

On Tuesday members of the board also doubled down on the efficacy of the MMR vaccine.

“I think that's something that also is forgotten that millions of kids have died worldwide of measles and, the vaccine has been literally lifesaving worldwide,” said DPH Commissioner, Kathleen Toomey.

The MMR vaccine provides almost total protection against measles, and over decades of use, has been proven to be safe with minimal side effects.

Yet, concerns from people who question vaccine safety have only gotten more pronounced since the COVID-19 pandemic, which created a massive drop in trust for public health. Since then, many states including Georgia have reported a slight rise in families opting out of routine vaccines.

Some officials in Texas and other infectious disease experts have credited vaccine misinformation and conflicting language trickling down from the federal government in part for how widespread cases there have become, and how difficult it has been to tamp them down.

It wasn’t until this past weekend, after a visit to the family of the second child who died from measles, that Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr took a clear stance, at least in the public sphere.

On X, he confirmed additional deployment of supplies to affected areas in Texas including “needed” MMR vaccines, and he promised support from the CDC.

“The most effective way to prevent the spread of measles is the MMR vaccine,” he wrote.

But on Tuesday, Georgia DPH Board Chair James Curran, without naming the HHS secretary, expressed concerns over recent indications of support for research into disproven links between vaccines and autism, saying that the federal government put a “disreputable” person in charge of that investigation which could open floodgates to further skepticism around vaccines.

“Bringing that up again is gonna be continuously problematic,” Curran said.

The onus of addressing such research, and the risks it could suggest, would likely fall on public health departments and local providers.