Caption

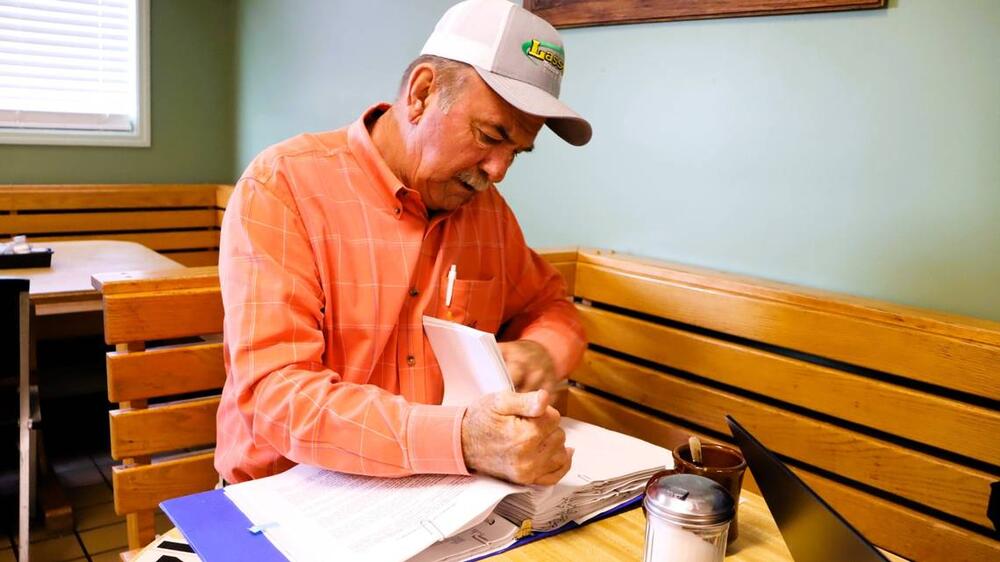

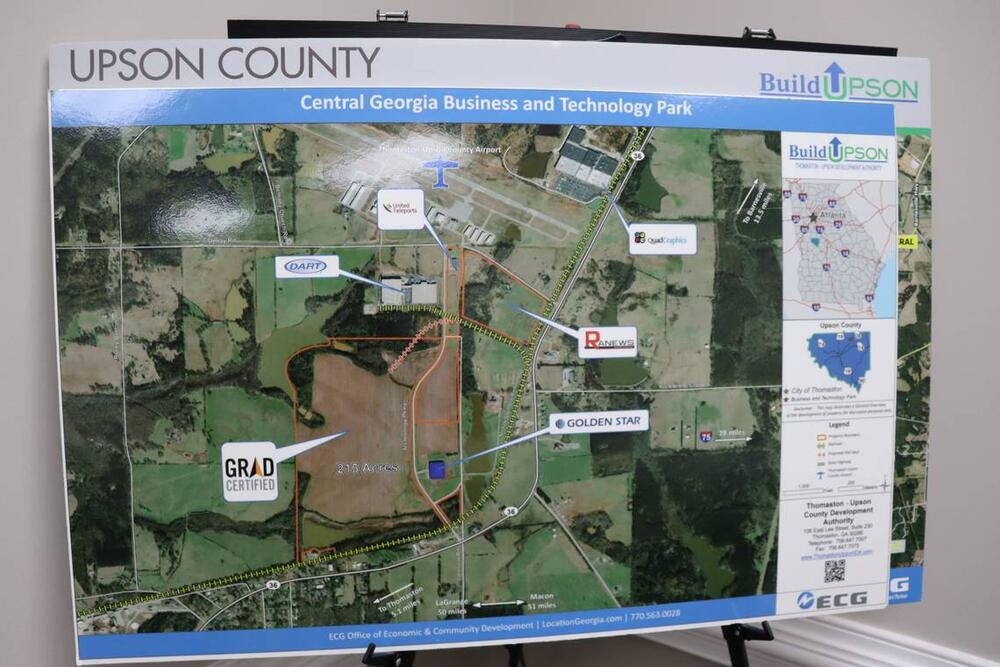

Rusty Blackston sorts through his binder of notes and paperwork about the Brightmark Thomaston Circularity Center at a restaurant in Thomaston in April 2025.

Credit: Kala Hunter / Ledger-Enquirer

Rusty Blackston sorts through his binder of notes and paperwork about the Brightmark Thomaston Circularity Center at a restaurant in Thomaston in April 2025.

Last April, when a 2.5 million square foot plastic waste intake plant was proposed in Thomaston — about halfway between Macon and Columbus — it ignited opposition from residents and environmental advocacy groups.

Months later, a coalition was formed to oppose the plant: the Upson Environmental Government Transparency Group, made up of impassioned local opponents, Georgia-based scientists, and environmental advocates locally and from around the country.

A year later, the California-based plastic-waste solution company, Brightmark, still is pushing to build what it calls the Thomaston Circularity Center. The company wants to help resolve the plastic pollution crisis by turning 400,000 tons of plastic waste per year into its original liquid form, oil, by pressurizing and heating plastic at a very high temperature (anywhere from 500 to 1,300 degrees) until it forms a slurry substance. That will then be sold to customers to create “the building blocks of new plastic,” according to Brightmark.

The process is called pyrolysis. And the Thomaston-Upson County Industrial Development Authority is betting big on the plant’s success with an $879 million dollar tax abatement bond. That is to be given to Brightmark after it receives an air quality permit from the Georgia Environmental Protection Division, which the company plans to file “soon,” Brightmark CEO Bob Powell said in a statement.

Despite advocates’ opposition, a big boost to the local economy is one reason why there are people supporting the plant.

“They’re gonna bring 197 jobs here at an average wage of $51,500 a year, nothing to sneeze at for a community of 28,000 people,” said Chase Fallin, Industrial Development Authority Board chairman.

But scientists and advocates within the Upson transparency group see red flags in whether this is good for the environment; they don’t believe the promises of the pyrolysis process, and say the entire process creates harmful byproducts and potential hazards.

“The scientist in me doesn’t buy it,” Amy Sharma, the executive director of Science For Georgia, said. “It’s greenwashing. Plus, there isn’t good stuff in plastic, there are 16,000 chemicals in plastic outside of just fossil fuels: like heavy metals, lead, cadmium, benzyne, toluene. These will be released when the plastic is broken down in the pyrolosis process.”

Jess Conard, an advocate at Beyond Plastic, an anti-plastic coalition, said pyrolysis is not a solution, and pointed to issues that have occurred at several of these types of plants, causing most of them in the U.S. to reportedly close.

“It’s a false solution, it’s a scam,” she said. “It’s just shifting the way we see pollution. You’re taking one type of pollution and shifting it to another form.”

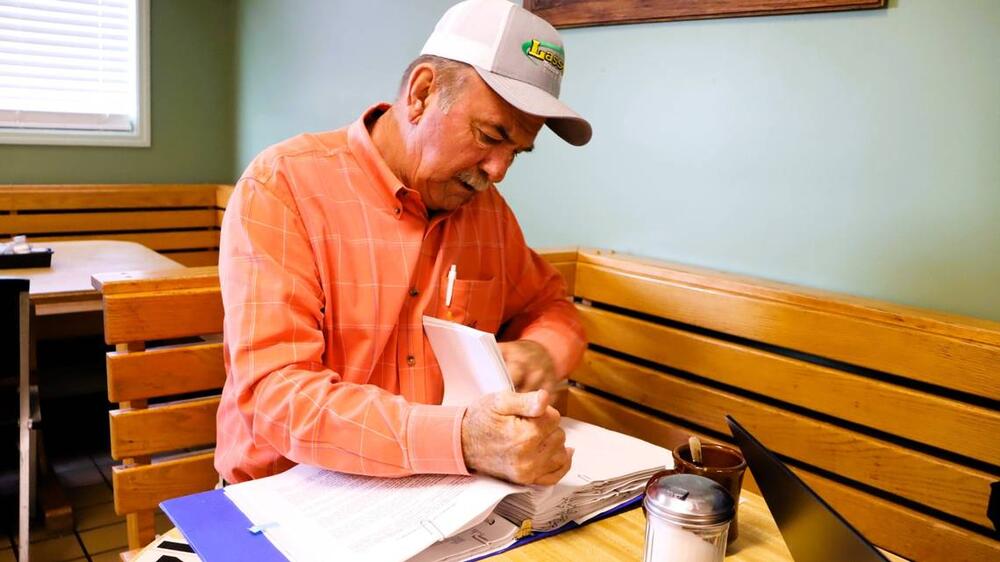

The 100 acres of land within the Thomaston Upson Industrial Park that Brightmark has its eyes on — and has paid $200,000 in earnest money for — sits about 5 minutes from central Thomaston. Current industry exists in the area, such as Dart (Solo plastics) and Quad Graphics.

“The mission of Brightmark is to provide solutions for helping the planet,” Slade Gulledge, the executive director of the Industrial Development Authority, said. “The idea that they would come to Thomaston and try to do something that would be detrimental to the environment is absolutely 180 from what their mission is. This is the building blocks of future plastic. They want to sell (their product) back to petrochemical companies and use it to help make renewable plastic.”

Gulledge said this will be a huge investment for the community.

“A $900 million investment is a considerable chunk of change,” he said.

The back of the Upson Beacon newspaper on April 8, 2025, has a community clean-up ad sponsored by Brightmark.

Despite the financial upswell Brightmark’s plastic processing plant promises to bring to a community which desperately needs economic surplus – they had an economic downturn after their textile mills and companies like Yamaha left the 1990s — the Upson Environmental Transparency Group is not interested in Brightmark. The group’s disdain and distrust has grown, and so has the size of the group.

It’s difficult to escape the word Brightmark, even if spending just one day in Thomaston. Along State Route 36 near the industrial part of town, Central Georgia Business and Technology Park, signs in yards read “Say no (to) Brightmark.”

A house along State Route 36 in Upson County, across the street from the industrial park, with a sign opposing Brigthmark’s plastics plant. It’s one of 300 signs distributed throughout Thomaston-Upson County by the Upson Environmental Government Transparency Group.

Meanwhile, on the back of the Upson Beacon newspaper, Brightmark has taken out full page ads that read “courtesy of Brightmark.” Powell spoke on the local radio station in March, talking about the plant and his eagerness to work with Thomaston residents.

While Brightmark and the IDA have made negotiations, activists in the Upson transparency group have kept themselves busy researching the company, staying active on Facebook groups, creating the signs to put in front yards and sending flyers in the mail.

Mike Greenman, 71, is seven years into retirement after working at the local paper printing processing plant, Quad Graphics. He joined the leader of the Upson transparency group, Rusty Blackston, a few months ago. Greenman went door to door educating residents whose homes border the industrial part of town and asked to put the signs in their yards. So far nearly 300 yard signs have been distributed.

Greenman is most concerned about the chemical byproducts in the process, such as toluene. He was familiar with toluene from previous work he did, and called it “nasty stuff.” Toluene can have lasting damage on the central nervous system from both acute or chronic exposure and cause other severe health effects, according to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

Mike Greenman lists why he opposes Brightmark’s plastic waste plant in Thomaston, Georgia. His biggest concern is chemicals such as benzyne and toluene, byproducts of the plant’s pyrolysis operation.

Rusty Blackston, a 70-year-old former IDA commissioner, former county commissioner and a semi-retired poultry farmer, created the Upson government transparency group out of concern for the well-being of his family and grandsons, after learning Brightmark’s current plant in Ashley, Indiana, caught fire a few years ago.

Plus, alarm bells went off for him when Macon-Bibb County turned down Brightmark’s plant proposal in 2022.

“It’s about the product and the danger of this product,” Blackston said. “If it’d been a coffee cup company, anything computers, anything other than this type product, I’d be doing backflips.”

In December, Blackston got a petition with 600 signatures asking to stop Brightmark from building the plant. He gave that to the board of commissioners.

“The answer I got was just like a deer in headlights, dumbfounded,” he said. “They think they don’t have any control over this. And I advised them, they have more control than they realize, but they don’t want to hear any options.”

Now Greenman and his friend Dana Fowler, a 61-year-old born and raised in Upson County and a current employee of Quad Graphics, are working to get 5,000 flyers in the mail to let residents know about Brightmark and ask them to sign a petition. So far it has 200 signatures since the flyers went out in mid-April.

Greenman, Blackston and Fowler all live 2 to 5 miles from the industrial site and share concerns about the possibility of an explosion, or fire or other hazards.

“Concern for the environment was first and foremost in my mind,” Fowler said. “What really sticks with me is, ‘how will this impact generations to come?’ I’m worried about the safety of a fire and the chemicals they would be using. We do use chemicals at Quad Graphics, but not the type that would be used there.”

Much of the concern from the opposition group comes from Brightmark’s plastic-to-oil plant in Ashley, Indiana, which caught fire in 2021. No one was injured, but it raised eyebrows in the Upson community.

“My biggest concern is fire,” Upson County Commissioner Dan Brue said.

Thomaston has a fire department. But, Upson County only has a handful of volunteer fire departments.

“We have six volunteer fire departments in the county, but our members of our community pay extremely high homeowners insurance in this county because of fire protection ratings,” Brue said.

Upson County Commissioner Dan Brue sits down to talk with the Ledger-Enquirer April 8, 2025. Brue is also a board member, by default, of the Industrial Development Authority.

Powell said they take fire risk “very seriously” in a statement emailed to the Ledger-Enquirer.

“Similar to our Ashley Circularity Center we will establish a detailed Emergency Action Plan and appoint accomplished safety and quality professionals who will lead our workplace safety efforts,” the company said in an email. “We will invest in foam fire protection monitors, high density sprinkler systems, early smoke and carbon monoxide detectors and other technologies.”

Fallin and Gulledge both said there is a possibility that a fire station gets commissioned at the industrial park to serve existing industries and Brightmark.

Fallin’s position is voluntary, and he spends about 10 hours a week on it outside of his general contractor job. Blackston, though semi-retired, spends about the same amount of time per week on fighting this plant.

When the Upson transparency group caught wind that Brightmark filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in March, the already unenthusiastic group was gobsmacked.

Brue’s phone lit up with texts from the opposition group about the announcement. Powell, the CEO of Brightmark, called the IDA chairman and executive director to let them know about their “strategic restructuring plans.”

But for the opposition group, this news didn’t make sense and created more distrust.

“To me, it’s a shell game,” Blackston said. “I don’t understand big corporations like that, but I don’t think there’s a true intent to the project itself.”

Gulledge and Fallin were notified right away when Brightmark filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in March.

Gulledge called Brightmark “very transparent, forthcoming and a good partner.”

Fallin said big business operates differently than “you and I do.”

“Our sitting president has done this four times through his current business tenure,” Fallin said. “Nothing has changed with our deal in Thomaston. This all has to do with debt restructuring.”

For Brue, he says clear communication has been inconsistent and he empathizes with Upson County residents.

“Brightmark has done a poor job at best as far as public relations in this community,” he said. “The feeling in the community is, ‘how can we trust this company?’”

Brue was front and center during a heated county commission meeting on March 25, a week after the bankruptcy was declared, where over 100 people filled the room and spanned out into the hallways.

“People were in an uproar,” Blackston said.

A handful of the Upson transparency group members gave public comments. Several of the public comments requested a surety bond on Brightmark’s plant as a way to hedge against costs. The group wants the county to have money to cover potential environmental costs, health impacts and more, and they feel the surety bond would do that.

“We request that the board of commission take proactive measures to protect this safety of our citizens and the environment,” Tami Boyle said. “We want the board of commission to work with the county attorney and any other knowledgeable individuals to develop an ordinance, a resolution or a binding legal contract requiring Brightmark to establish a trust fund, a performance bond or a surety bond.”

After Boyle finished, applause echoed throughout the room.

Greenman spoke after Boyle and emphasized the need for a pause on the project, or a moratorium. Then Fowler spoke, saying “this could be one of the largest downfalls in community history.”

Dietitian Mary Pat Jones said she appreciates clean air and clean water during her public remarks.

“I don’t want money, I want health,” she said.

Brue doesn’t think he can issue a moratorium, which would pause the project. He said the IDA and Brightmark already have a binding contract, and he doesn’t think the county commission can interfere. But he’s interested in a surety bond. Brightmark’s CEO told Brue he was interested in what Boyle said, and also was looking into a surety bond.

Conard, from Beyond Plastic, emphasized the power of a local authority and said this can be prevented through some of the ideas Boyle suggested.

“I can not be more clear if there was ever a time to speak up now is the time for civic engagement level to be pulled,” Conard said. “You do not want plastic to be burned in a community near your home.”

Conard, who witnessed the East Palestine, Ohio, rail car explosion and has been a public safety advocate for years, says a moratorium or an ordinance to delay the project is smart on all platforms.

“It gives the (commission and IDA) time to look into the bankruptcy,” she said.

Brightmark didn’t say what it’s production volume would be at Ashley, just that the company has recycled “millions of pounds and continue to increase production,” officials said in a statement.

Fallin and Slade both visited the Ashley plant and said it was clean and safe, but recognized it might have been spotless for visitors in town.

Brue, on the other hand, said he would not go to Ashley on Brightmark’s dime.

Additionally, the deal between Brightmark and Upson IDA suggested the property tax abatements from the bond would be up to $35.8 million dollars over 10 years.

Fallin believes that the earnest money and bond issuance fees haven’t put Thomaston-Upson County at risk, but rather made the money.

“If the bankruptcy goes sideways or if they don’t get the air permit, we’ve not lost anything,” he said.

Chase Fallin, Industrial Development Authority Board chairman, explains why he supports Brightmark and itsmission to bring the Thomaston Circulatory Center to Upson County.

It is still being determined whether plastics would be brought in by truck or rail, according to Powell’s latest statement to the Ledger-Enquirer.

As far as shipping the final product to customers, Brightmark would like to “utilize rail.”

Sharma’s group estimates if they use trucks, it would be around 50 per day to get to the 400,000 tons per year, creating a significant amount of noise and air pollution.

The Thomaston-Upson County Development Authority Georgia Business and Technology Park. The red outline shows where Brightmark would build its 100-acre, 2.5 million square foot plastic plant.

The entire facility is expected to require 15 megawatts of power. That is enough electricity it takes to power anywhere from 6,000 to 13,000 homes.

“It’s a (potential) carbon triple whammy,” Sharma said.

Between the truck transit, the pyrolysis process, and if the 15 megawatt plant if it isn’t powered by clean energy, the venture would have three large sources of carbon dioxide pollution.

Sharma said truck transit would release carbon three times, while it’s processed, and if it’s not powered by clean energy, calling it a “carbon triple whammy.”

The company is “still exploring options for how the building will be powered.”

This story comes to GPB through a reporting partnership with Columbus Ledger-Enquirer.