Section Branding

Header Content

Carolina to 'Cowboy Carter' and back: A celebration of Black roots music finds a home

Primary Content

Recall the sound that set the salty, downhome tone for Beyoncé's history-making single "Texas Hold 'Em." The first notes you hear on the first track by a Black woman to top Billboard's Hot Country Songs Chart, the spark that ignited popular discourse about a global pop megastar circumventing the gatekeepers of the country music industry, are a circling, syncopated old-time banjo figure. That part was played by Rhiannon Giddens, whose name you'll know if you've followed folk music over the last 20 years. In that time, Giddens' work has illuminated a Black banjo lineage that was long excluded from the official narrative of country music's origins. That's the authority her contributions carry.

An even more explicit historical signifier on Cowboy Carter, the album that would eventually win the 2025 Grammy for album of the year, are interludes featuring the, warm knowing speaking voice of the Black country singer Linda Martell, whose accomplishments in Nashville in the late 1960s had long been championed by one of her spiritual descendants, Rissi Palmer, who herself had made (modest) chart history in the 2000s. Since Bey herself certainly wasn't out there doing interviews correcting the long held perception that country music is the province of whiteness, Giddens, the 21st century folk luminary and interdisciplinary virtuoso, and Palmer, the beloved roots and soul-steeped singer-songwriter and artist advocate, were high on the list of proxies that media outlets called on to be talking heads.

But to fixate only on that moment of massive mainstream attention is to miss the true priorities of the movement to reclaim the Black roots of folk and country music. Palmer and Giddens traveled wildly different career paths to reach the point where they can each see the community-building work they've done right alongside their artistry, contrary to the machinations of the industry, bear fruit. One measure of the distance they've traveled: This weekend, they'll be among those celebrating the movement's self-generated moment on stage and off all over downtown Durham, N.C. at a new festival called Biscuits & Banjos.

It was Giddens' idea to gather an impressive lineup of Black roots performers and scholars, as well as literary and culinary figures, at a deliberate remove from the country music power center of Nashville. Durham, with its rich tradition of Black entrepreneurship, is the city Palmer calls home, in the state where Giddens and her celebrated band Carolina Chocolate Drops locked in on their purpose. They'll all be present — the Chocolate Drops reuniting after numerous changes in lineup and a decade-plus hiatus, Giddens and Palmer engaging in a panel discussion and each curating stages — along with an array of predecessors, peers and descendants. And they'll celebrate progress they've made — according to their priorities, not the industry's — over the last 20 years.

The roots of Biscuits & Banjos lie in an event held two decades ago. Giddens kicked off her performing life with classical conservatory training, then followed her old-time interests, picking up bread crumbs of evidence — from books, a listserv, the 2005 Black Banjo Gathering at Appalachian State — that the stuff she was digging had never been the exclusively white domain it was made out to be. The Gathering — whose 20th anniversary Biscuits & Banjos will mark — has typically been treated as a footnote in the story of the Chocolate Drops, the string and jug band that she formed with Dom Flemons and Justin Robinson. But in significant ways, the setting where the three pickers found each other and their mentor, fiddle-playing piedmont elder Joe Thompson, forecasted the multifaceted work they were headed for. There was participatory jamming going on, and there was plenty of scholarly discussion too. Even in that friendly space, Giddens remembered, she and her comrades were vastly outnumbered by white attendees.

The Chocolate Drops gained notice for the nimble showmanship and imaginative zeal they brought to their minstrel-era repertoire, but the novelty of a young, Black, old-time band also turned heads. Like many new groups, they worked hard to win over unfamiliar audiences. But they faced an added burden — people always expected them to explain themselves. "All three of us grappled with what it meant to be who we were," Giddens recalled, "and to be interested in music that our culture told us we shouldn't be interested in, and that dominant culture told us we were interlopers in, but actually was an inheritance of everyone."

It's one thing to consume the literature on the African origins of instruments and techniques that came to the U.S. through Transatlantic slavery, then evolved in the hands of enslaved entertainers and their free Black descendants, who mightily shaped what came to be categorized, artificially, as white hillbilly music. But that tale of Black string band erasure wasn't purely theoretical for Chocolate Drops. They learned at the feet of Thompson, a living link who was then nearing the end of his life, but still active. In an epic 2019 New Yorker profile, John Jeremiah Sullivan traced the lineage of North Carolina Black string band performers from Giddens and her comrades through Thompson's family line all the way back to one of the most famous, and forgotten, musicians of the 20th century, Frank Johnson. "I think part of our secret sauce was that we had Joe," Giddens mused. "We were there to proselytize about his music and his culture and his history. And it's really, really hard to mess with that."

In every era, Black practitioners from Lesley Riddle to DeFord Bailey, John Hurt to Etta Baker, the Ebony Hillbillies to Taj Mahal and Otis Taylor to Toshi Reagon have put their stamp on folk and country forms, and generations of performers have attempted careers in modern Nashville. But they've often been perceived as exotic anomalies, not contributors to a cohesive and foundational lineage.

When Giddens left the Chocolate Drops to make solo albums utilizing her classically trained voice and composing abilities in sublime and limitless ways, she also aimed her change-making efforts where she saw pockets of consolidated commercial influence. In 2017, she gave the keynote address at the International Bluegrass Music Association's annual conference, a convening of the stakeholders and stars of the insular bluegrass business. After warming up the crowd with reflections on cross-cultural exchange in her own, racially blended Southern family, she went right for a subject that's sacrosanct in bluegrass circles: where the Bill Monroe sound originated.

"In order to understand the history of the banjo and the history of bluegrass music," she told those assembled, "we need to move beyond the narratives we've inherited, beyond generalizations that bluegrass is mostly derived from a Scots-Irish tradition, with 'influences' from Africa." Right then and there, she gave a rebuttal: "It is actually a complex creole music that comes from multiple cultures, African and European and Native — the full truth that is so much more interesting, and American."

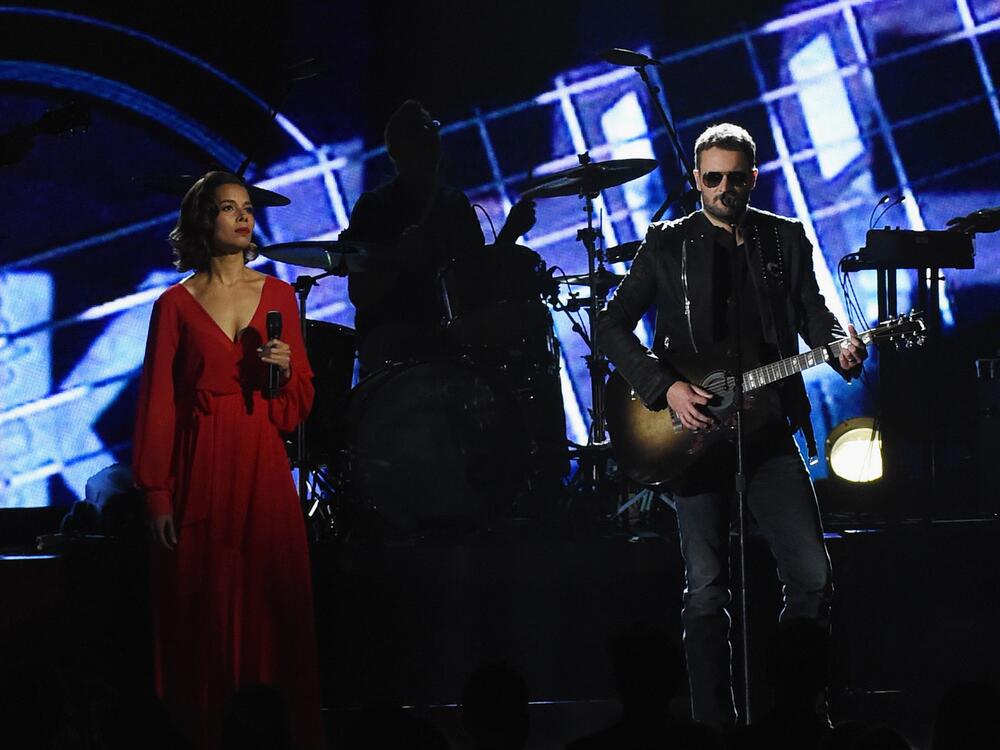

Giddens set her sights on country music, signed with a well-positioned manager, recorded a song with Eric Church, one of the genre's most artful hit-makers, and landed a role on the primetime drama Nashville, with its soapy, stylized portrayal of performers trying to gain, or hang onto, industry status. She even persuaded the showrunner to add a scene where she taught a group of Black children about the African roots of the banjo. "That felt monumental to me," she said. But few took notice. She felt the same demoralizing lack of response from other musical efforts, including a reinterpretation of the Patsy Cline classic "She's Got You" that Giddens animated with indignant longing. Her sense of futility mounted: "'I can sing the hell out of country music. I play fiddle. I play banjo. If I was white, you'd be all over me, right?' Maybe. Maybe not. But it was hard not to feel like, 'I have everything that you need, and nobody cares.'"

Palmer experienced her own version of that indifference. Where Giddens has focused on history that played out more than a century ago, she worked towards a more conventional model of country success, before embracing the full scope of her roots sensibilities as she sets the record straight on the modern country music industry's aversion to Black talent. Two decades ago, she was hustling to make headway in Nashville. She'd already proven her promise as an agile, emotionally articulate singer to talent spotters, including pop-R&B production giants Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, whose offer she declined. But the process of trying to land a country record deal dragged on for seven years. Eventually, she signed with an independent label out of Atlanta that dabbled in multiple genres.

Palmer could see that the country music community prided itself on its collegial culture. Everyone knew everyone, and old hands took newbies under their wings. She was shut out of that chumminess. No one even thought to connect her with other Black country performers. "Had I not felt like an island in the very beginning of my career," she reflected, "I think about how different things could have been."

Nashville interrogated her country authenticity with a skepticism that it seldom turned on her white counterparts, and she had no one to commiserate with. "Everybody at the time was so worried about me being sincere," said Palmer. "'Is she really wanting to make country music, or is she just using country music to get over to pop music?' Which is the most asinine [assumption to make about] a young, Black girl in the early 2000s."

Aware of the suspicion that Palmer had crossover aspirations, her team cautioned her to limit the R&B vocal flourishes on her self-titled debut album and make it "the most straight-ahead." When she absolutely nailed the punchy, energetic phrasing of mid-2000s country hits, that still wasn't enough. After achieving only modest chart success with her 2007 single "Country Girl" — her contribution to the grand tradition of country songs that take pride in a down-home state of mind — she gradually decided to distance herself from Nashville.

In 2015, when I first interviewed Palmer, she was back in town during CMA Fest, but steering clear of the country music industry's fan-targeted extravaganza. Instead, she played a set at Sunday Night Soul, a haven for the city's grown-up neo-soul and R&B heads. I could tell from the way she spoke that she was entering a stage of interrogating and reinterpreting her professional experiences. Years later, she finally got the chance to compare notes with Miko Marks and Mickey Guyton, who'd each made their own valiant attempts at advancing up the country charts on the strength of the performing abilities and styles they'd refined. That was the missing piece. Palmer fully developed her critique of the structural realities they'd all tried to navigate. "I can only speak for me," she said. "It took a lot of the weight off, because a lot of my anger was turned toward myself and not toward the bigger [system]."

Around the same time, she started taking note of cursory overviews of Black country figures proliferating online. "It bothered me so much to see either the credit not going to people that it deserved to go to," Palmer explained, "or the story just being told in this really wrong way and making it seem like Black people didn't have anything to do with country music from the very beginning." Lineage is a matter of great consequence in country, roots and folk music. To be assured of your place in the present, you need to be able to trace an unbroken line back to forebears in the past. So many others had been erased from the story that she feared the same could happen to her, and keep right on happening. She decided to put her knowledge to work: "'Well, if it's not going to be told in the correct way, then why don't you tell it?'"

One of Palmer's prime concerns was elevating elders who hadn't gotten their due. Especially Martell, who made one standout country album in the late '60s, played the Grand Ole Opry several times and nearly cracked the top 20, before a controlling executive got her blacklisted around town. Her story had gotten as buried as her career. Palmer's personal campaign to bring serious attention to BIPOC country and Americana voices took the form of an interview show, named for Martell's album Color Me Country, and was soon picked up by Apple Radio.

An independent artist herself, Palmer knew the growing number of unsigned artists she was getting acquainted with needed actual resources, not just a bit of recognition, to keep going. Her Color Me Country Foundation provides microgrants and mentoring, and curates festival stages, including one at Biscuits & Banjos. "It's just really about giving people opportunity, giving them good advice and then giving them money that they don't have to jump through hoops for," summarized Palmer. "And that's really all I want. I don't want anybody dedicating their album to me. I don't want to be anyone's manager. I don't want to run a record company, or any of those things. I just want you not to do the dumb stuff that I did and have an easier time."

Giddens has nudged artists along in her own way. As the Chocolate Drops became a draw on the folk circuit, they provided visible and accessible encouragement to other aspiring young, Black pickers. "I gave Kaia a lesson," Giddens noted, referring to the Grenadian-Canadian singer-songwriter Kaia Kater, brilliant at applying inner insights to global histories and recent winner of a JUNO — the Canadian equivalent of a Grammy — for contemporary roots album of the year. Giddens remembered coming away from their long-ago instructional session insisting, "'I can't teach you anything, girl.'" She jammed with Jake Blount, a fiddle and banjo player who would go on to intellectualize and radically reframe old-time tradition through the lens of Afrofuturism, at a gathering. But it was when she heard Amythyst Kiah cite the Chocolate Drops as an important contemporary inspiration — a major factor in helping Kiah translate her collegiate studies of Appalachian music into an appealing artistic path — that Giddens was struck by a realization: She and her band mates had a hand in bringing their fractured musical lineage back to robust and open-ended life. "It really means a lot when you can see people coming behind you," she reflected, "because that means you've done your job."

Soon she invited three other artists — all of them singing, songwriting Black women who play various styles of banjo — to collaborate as Our Native Daughters. Leyla McCalla, who'd briefly toured with the Chocolate Drops, Allison Russell and Kiah were still emerging as artists in their own rights. This was Giddens sharing her platform. "I want to use it for all it's worth while I have it," she said. They made an album together, summoning the spirits of women across the African diaspora who'd guarded their senses of personhood as their freedom was stolen.

Maintaining all these efforts to further their own careers while also advocating for others' requires a tremendous amount of work. Palmer's come to see it, with good reason, as "a whole other job." It's part of why she's gone half a dozen years without releasing an album of her own, something she'll remedy this year. Palmer has been reminded how much she values greater stylistic flexibility than she was originally permitted, and in her own music, she makes room for meaningfully elongated soul phrasing, emphatic gospel feeling, singer-songwriter intimacy. She's come to understand what's necessary — for her — to sustain a satisfying career: "I don't care if I ever get signed in Nashville. I don't care if any of those things ever happen for me ever again. Because I got people, and I know that I'm good with my people, and my people are good with me."

Giddens has continued to take on podcasts, speaking engagements and other projects of her choosing where she laid out her belief that musical traditions arise through a boundary-transcending creolization process, and her increasing distrust of the recording industry and the artificial racial segregation baked into its beginnings. All the while, requests for her to rehash the most basic principles of that history in interviews keep coming. She's spent the last two decades "being questioned," simply because of how the intersection of her interests, expertise and racial identity disturbs narratives that calcified around music traditions. That's been enormously depleting: "Every interview takes so much energy," she said, "because I'm like, 'I have to be as correct as I can possibly be, because I'm representing.' … I'm aware that this is a movement, and it's not just me. It never was just me." When she can, she told me, she suggests they instead speak with other Black banjo players who aren't yet as well known as her. "But sometimes, they want you, and if you try to give them somebody else, then they just abandon the story or they just abandon that part of it."

It's taken many people — not just Palmer and Giddens — to energize this movement to reclaim the Black roots and prerogatives of country and folk music. They have a wide array of approaches and aims, but share a desire to combine the power of their labor and create their own spaces outside of the white-dominated industry system.

Biscuits & Banjos is one of those spaces, a gathering of individual organizers. Giddens will reconvene with multiple versions of the Chocolate Drops — fresh off the two members from North Carolina, Giddens and Robinson, returning to the repertoire they first learned from Thompson, their mentor, on a frisky, new fiddle-and-banjo duo album, What Did the Blackbird Say to the Crow. She'll help lead a square dance with a band she's assembled and speak on panels alongside Palmer, who's also hosting her multi-artist Color Me Country Revue, and Alice Randall, the songwriter and novelist who spent her time in the country music industry in the '80s and '90s pushing for both early country's Black pioneers and contemporary country's Black contenders to be taken seriously. Randall told the story herself in last year's revelatory, memoiristic history My Black Country, and finally got to hear her own songs sung by Black women when Palmer, Giddens, Russell, Marks and McCalla and a number of their artist peers recorded them, and in the process, embraced her as predecessor.

Black Opry co-founder Holly G, who frequently produces her own showcases of Black singer-songwriters, will discuss those efforts on a panel with Brandi Waller-Pace, a banjo-playing former teacher whose formidable nonprofit work includes educating educators and putting on a Black roots music festival in Fort Worth that recently had its fifth edition. Kater and Blount will take the stage with their new-generation, all-Black string band New Dangerfield, which also features bluegrass banjo phenom Tray Wellington and bassist Nelson Williams.

These efforts don't represent a wholesale transformation of the music industry, but they have significantly reshaped the landscape that Black roots artists inhabit. "That success is in spite of the industry, in spite of what goes on in mainstream music," Giddens emphasized. Over the last several years, scenes and coalitions they've cultivated have reached critical mass. And since the system elevates the history made within its boundaries, Giddens invited all of the figures I mention here, and many more besides, to Biscuits & Banjos, where they won't be treated as an exotic presence and their labor and accomplishments, both individual and collective, will take priority.

The model that Giddens chose for the festival itself is a culmination of the movement's push for its own spaces that aren't beholden to extractive, commercial practices. "It's not about how much money it's going to make," she noted. "It's not about what brands we can bring in." She worked with the nonprofit Unmanageable Arts to find the funding, source festival staff from the local community and ensure that a good chunk of programming is free to the public.

"There's a lot of us out there doing this work," she went on. "So I wanted to create an environment where we could come together and we could refresh. It's not just for the audience. It's also for us. Like, we get to see each other. We get to play together. We're usually the raisins in the oatmeal, and we're kind of scattered across the firmament, but we actually get to come together and have this moment."

"What we're doing in our culture, I don't feel like it's celebrated enough."

So, she took it upon herself to aim the spotlight where she feels it belongs.