Section Branding

Header Content

What Pundits Get Wrong About The Latino Vote

Primary Content

Every 30 seconds, a Latino turns 18 and becomes eligible to vote — and that's a huge reason why this year, for the first time, Latinos are projected to become the largest nonwhite voting demographic. This week's episode of Code Switch focused on these Generation Z Latinos — a fast-growing group of voters who could have a huge impact on the 2020 presidential election.

And yet, for decades, pundits and politicians alike have predicted that Latinos will have a huge impact on elections — and that's never quite panned out. (Latinos have, historically, had lower turnout rates in elections than other racial and ethnic demographics.)

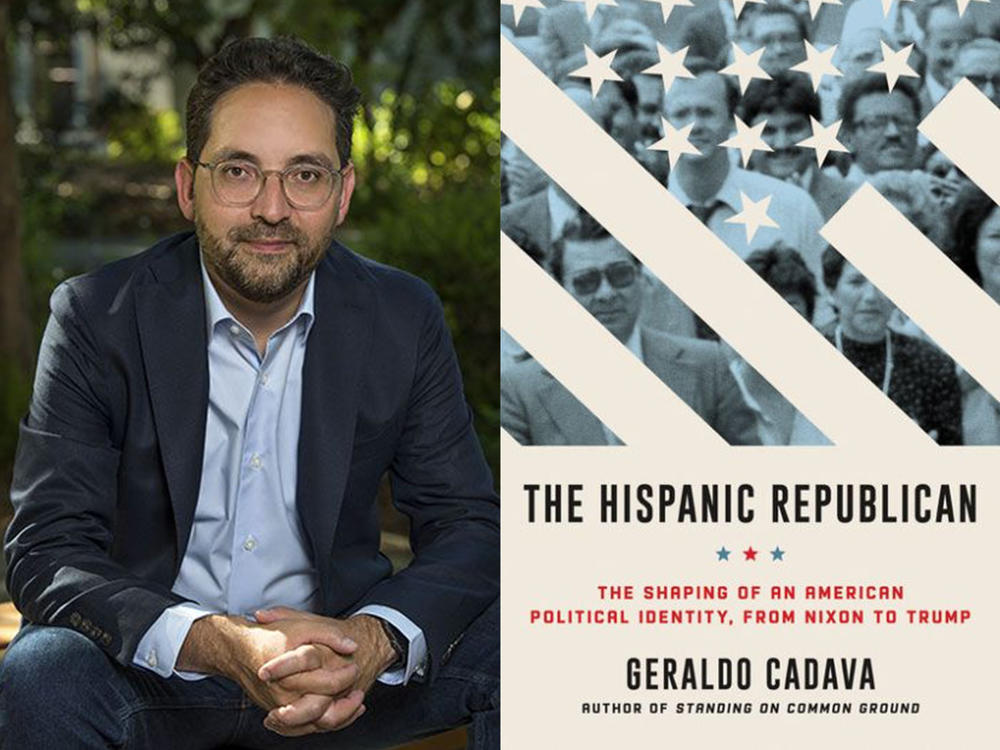

So to understand how the Latinx vote has played a part in past election cycles, we talked to Geraldo Cadava, a history professor at Northwestern University and author of the book The Hispanic Republican: The Shaping of an American Political Identity, From Nixon to Trump. Here's the extended cut of our conversation, which has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Your book is all about how Latinos have arrived at their politics throughout history — specifically Republican Latinos. How would you sum up how that process works?

Latinos became increasingly politically active after the World War II years; many Latinos served in World War II, and that gave them expectations about how they should be included in all aspects of American society: socially, economically and politically. Many more Latinos went to college, bought homes and also began to vote and become politically active.

And the parties really started to reach out to Latinos after World War II, because the Latino population started to grow in areas like Texas, California, Arizona and Florida, which were becoming more and more electorally important. That's also the moment when Latinos themselves become more politically active as part of their drive for civil rights.

There was a moment in the late 1970s and early 1980s when the Latino population was growing, and Time magazine had a cover story that projected that the 1980s were going to be the "decade of the Hispanic." And there's an argument that Latinos are the "sleeping giant" who are about to awaken and control American politics in the late 20th and 21st century.

It's kind of amazing to me that every four years, there's this idea that Latinos are about to break out of their shell and really determine elections; it's like pundits and politicians rediscover them every four years.

Like you said, every election cycle, there's this idea that this metaphorical "sleeping giant" of Latinos will somehow come out of the woodwork and have a huge impact. Has it ever really panned out?

I should say, first of all, that the image of the sleeping giant feels like not a great image. There are all of these caricatures of Mexicans dating back to the early to mid-20th century, of us wearing serapes and sombreros, leaning against a wall with a bottle of tequila. We're always asleep and lazy, and it plays into this idea that we're apathetic. So I think the whole image is not great.

There is this perennial argument that we hear every four years, that Latinos are going to be the critical voters in this election. And I think that idea mainly comes from the fact that our population is growing. In 2020, we're projected to be the second-largest group of American voters, and the largest nonwhite group of voters. We are going to represent about 14% of the American electorate. This year, a Latino becomes eligible to vote every 30 seconds. And they're going to be a million more Latino voters this time than four years ago. So for all of these reasons, there's this idea that there's a lot of political momentum, and politicians had better start paying attention to us because we hold political power. But there has also been this ongoing sense that we're, to put it crudely, punching below our weight. We're not reaching our full potential because we don't register to vote in as high numbers as other groups.

But [high Latino turnout] has panned out in certain elections, like the 1964 election. For example, when Jimmy Carter beat Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter won in Texas. This was the last time that a Democrat won Texas. But he won by a very slim margin, and largely his victory in Texas was attributed to his success among Mexican Americans. I think we can point to the 2000 election in Florida, where George W. Bush won in Florida by a mere few hundred votes. And there was the Elian Gonzalez story, where George W. Bush and Jeb Bush, his brother who was the governor of Florida at the time, took a strong stance, saying that there's no way that Elian Gonzalez should be returned to his family in Cuba. And that really kind of galvanized Cuban American support for George W. Bush. And in 2012, by all accounts, Mitt Romney woke up on Election Day thinking that he was going to win the election — but Obama won. And in the days after the election, many made the argument that Obama's success among Latinos in swing states like Colorado and New Mexico and Virginia had made the difference and tipped the election in favor of him.

So if [the "sleeping giant" prediction] has ever panned out, it has panned out in particular elections, and in particular swing states, when they're very narrowly contested. But I think that many Latino get-out-the-vote organizers are still waiting for the moment when Latinos are going to realize their full political power. We know that Latinos vote at fairly low rates compared with other groups of Americans. So I think there is still a sense that our political potential is not yet fully realized.

Why haven't those voting turnout rates been higher?

For a long time, the [conventional] answer was that Latino voters are apathetic, and they don't care about politics. And that's the main argument that political scientists have tried to argue against for a long time. What they increasingly point to is a few different factors. One is that Latinos feel alienated from the political process. We've read reports that as late as August or July, some 60% of Latinos said they'd had no candidate reach out to them. And this is a kind of historical phenomenon. Latinos have argued for a long time that American politics and electoral politics wasn't made for them.

There are some other explanations about how many Latinos live in noncompetitive states, like California, Illinois and New York. And so they don't feel like their votes matter because they're not making a difference. And more generally, when we talk about elections and presidential politics, we are paying so much attention to Latinos in Arizona, Texas and Florida, critical battlegrounds. So Latinos in those states are hyper-visible, while Latinos everywhere else are ignored and invisible.

Apart from the idea that Latinos are apathetic, what are the biggest misconceptions that people have about Latinos and voting?

This is so tricky, because there's both a lot of truth and a lot of misconceptions. I mean, there's the way that people segment the Latino population in their minds. There's the idea that Florida is all Cubans and Cuban Americans when, in fact, Florida is incredibly diverse. There are large Mexican and Puerto Rican populations. And they have so many different interests and issues that they care about. So it's really hard to stereotype them. And there's the idea that the whole Southwest is Mexican American when, in fact, there are many Central Americans who live there.

Latinos are truly a national population and a growing population everywhere we live, but the way that we get talked about is still very much about the Cuban vote in Florida, the Mexican American vote in California or the Puerto Rican vote in New York. And, you know, there's almost like this hierarchy of our politics, from more conservative to less conservative — that Cuban Americans are the most conservative, Mexican Americans are somewhere in the middle and then Puerto Ricans are the most liberal of Latino voters. And there's a degree of truth to that; Cuban Americans vote for Republicans at higher rates than Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans, but Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans still vote for Republicans in really large numbers.

Let me tell you one fact that always astounds me: California has the largest number of eligible Latino voters: 8 million. Recent polls have shown that Donald Trump is earning somewhere between 25% to 30% of their support. That means that if all of those 8 million eligible Latino voters vote, more than 2 million Latino voters in California — the state of Proposition 187, the state where the Republican Party is dead — there will be more than 2 million Latinos who vote for Donald Trump. Compare that with Florida, which has 3.1 million Latino eligible voters. In 2016, 35% of Latinos in Florida voted for Donald Trump: That's around 1 million votes. And if that holds true in 2020, there will be more Latinos who vote for Donald Trump in California than in the state of Florida. And that's just one example of how, if you really dig in to individual communities and the politics of individual states, there's a lot that you would be surprised to learn.

And as you've been watching this election cycle, what do you see pundits and candidates misunderstand about this voting bloc?

When I hear pundits talk about the Latino vote, they're still assuming that all Latinos are out there are reachable by Democrats. And it's just a matter of committing more time, committing more energy and resources; Latinos are just waiting to be given a reason to vote for Democrats.

And I think that that completely misses the point that Hispanic Republicans have developed their partisan identities and their loyalty to the Republican Party over a long period of time. There are a handful of issues, like school choice or religious freedom or the ghost of anti-socialism and anticommunism, that continue to draw Hispanics into the Republican Party. There's a real diversity of political beliefs, and we need to acknowledge that Latinos are fully human, complicated political actors, rather than just kind of pawns that are easily poached or persuaded, just because a politician talks to them.

In your research, you've found that both Republicans and Democrats have called Hispanics "natural" Democrats or "natural" Republicans — but you disagree with this premise. Can you lay out why they say that, and why you disagree?

I don't think Latinos are naturally anything; that would mean that we're born with these fully formed political identities. To call them naturally liberal or conservative comes from a place of ignorance and not knowing much about who Latinos are as political actors.

Reagan is probably the most famous example of someone who tried to argue that Latinos are natural conservatives. And it was a statement that he apparently delivered to one of his Hispanic campaign organizers, an advertising executive named Lionel Sosa from San Antonio. Reagan told him, you know, you're going to have the easiest job ever, because Latinos are Republicans who just don't know it yet. And it was his campaign that, for the first time, tried to articulate these core values that supposedly brought together all Latino conservatives; they talked about family values, a hard work ethic, patriotism, belief in the free enterprise system and anti-communism, and all of the kinds of military sacrifices that Latino families had made for the United States. These are ideas we still hear them today uttered by the Latinos for Trump campaign. So they've been kind of remarkably persistent in their message over a long period of time.

I'm always reminded this year of that Joe Biden line that "if you're Black and support Donald Trump, you ain't Black." Democrats have had plenty of those moments when it comes to Latinos, too. In 2010, Harry Reid from Nevada said that he couldn't understand how even a single Hispanic could be a Republican. So I think you have both parties taking for granted that Latinos are naturally one way or the other. And I think when they do that, they risk not taking Latinos seriously as individuals and communities with deeply held political beliefs.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.