Section Branding

Header Content

This City's Coronavirus Safety Measures Could Become Best Practices

Primary Content

When the meatpacking industry in the U.S. started seeing a rise in COVID-19 cases, local officials in New Bedford, Mass., worried that their city was next. But the city took action, issuing emergency orders that safety experts say should be a model for workplaces across the U.S., if those orders can be properly enforced.

Jon Mitchell, the city's mayor, issued two COVID-19 orders on May 6 in a city where nearly 15% of the population works in manufacturing and 20% is Latino.

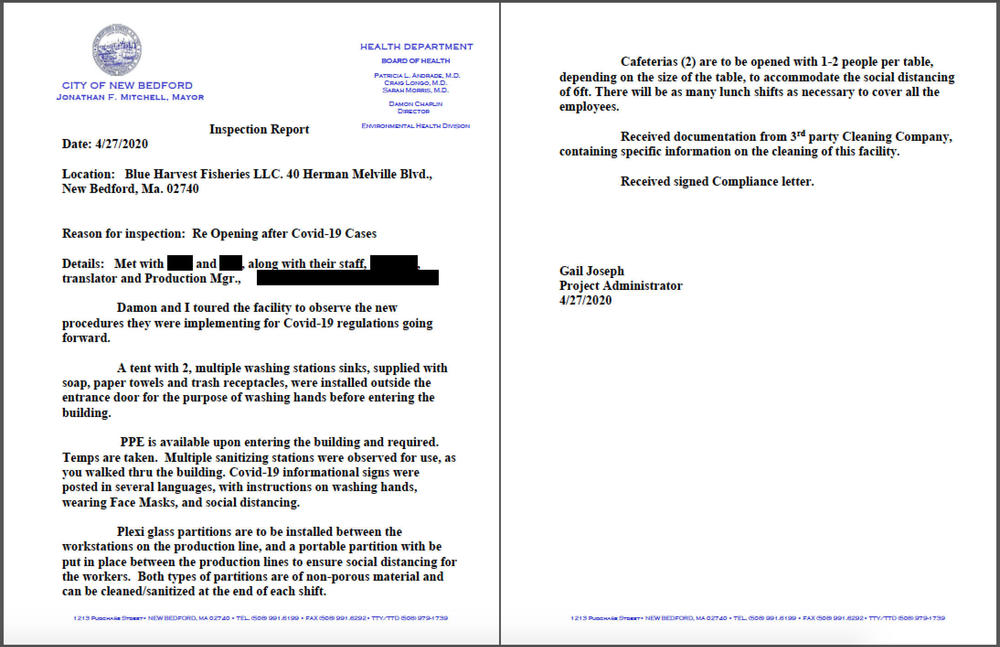

The first measure requires companies to report workers who have, or may have, the coronavirus to the local health department. The second requires industrial facilities such as fish houses to provide personal protective equipment, disinfect work areas and abide by social distancing rules. Every facility is mandated to have a health and safety officer who takes workers' temperatures at the start of every shift.

Companies that don't comply with the orders could face fines of up to $300 a day per violation and possible legal action.

"We looked at the experience of the meatpacking industry in the Midwest," Mitchell said. "And we wanted to make sure that we're doing everything we could to avoid an outcome or a set of outcomes like we saw there."

The move to protect workers in New Bedford began in mid-April when its essential fish-plant workers complained that facilities lacked adequate personal protective equipment and disinfectants and were overcrowded. The city's health department received two dozen workplace complaints and had to temporarily shut down several fish plants because of outbreaks.

Businesses across Massachusetts were closing. A fish-plant worker, who requested anonymity because she didn't want trouble at work, was worried that she could infect her child and elderly parents with the coronavirus: "I would come home from work and would 'fumigate myself,' " the worker said in Spanish. "I would spray my clothes and shower quickly. Just the fear itself made those first days super-stressful."

Jodi Sugerman-Brozan, executive director at the Massachusetts Coalition for Occupational Safety and Health, a nonprofit that advocates for safe conditions for low-wage workers, said no other U.S. cities have passed such stringent emergency orders.

"This emergency order is a great model for others around the state and across the country," Sugerman-Brozan said. "It sets very clear health and safety standards that were created in partnership with workers and reflects their demands."

New Bedford has already seen some positive changes. Working conditions are improving, and complaints have declined.

But resources are a problem.

In a city where Latinos account for nearly half of COVID-19 cases, the health department is struggling to track positive cases among fish-plant workers, many of whom don't speak English and some who are undocumented.

New Bedford has only eight inspectors who, during this pandemic, are now auditing fish houses and industrial facilities in addition to restaurants and are responding to other sanitation complaints.

"I don't care how many people you give me," Gail Joseph, lead inspector for the New Bedford Health Department, said. "There is no way we're going to get everything done in a routine manner. It's just impossible."

Cities across the country are struggling with a lack of resources. When the pandemic hit, there was an expectation that federal and state governments, which had been issuing guidelines for workplaces, would provide the resources necessary to implement those guidelines.

"It basically passes the buck of enforcement to local boards of health and municipalities," Sugerman-Brozan said. "Many of them have very little capacity to be able to do the work that needs to happen to inspect and enforce these regulations across their entire city."

The health department is trying to teach fish-plant managers and workers how to stay safe. The hope, health director Damōn Chaplin said, is that facilities will slowly become more compliant.

"We can't wait for the cavalry, and that's just been the [mayor's] mindset from the beginning," Chaplin said. "We are the cavalry."

Copyright 2020 The Public's Radio. To see more, visit The Public's Radio.