Section Branding

Header Content

Poison Control Centers Are Fielding A Surge Of Ivermectin Overdose Calls

Primary Content

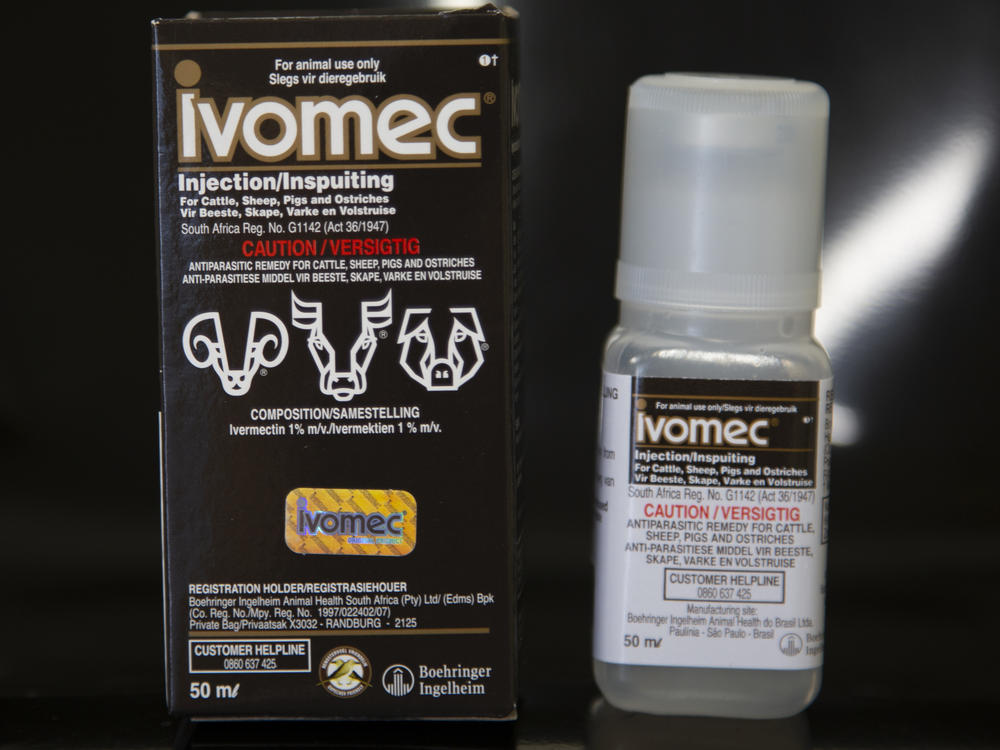

Poison control centers are seeing a dramatic surge in calls from people who are self-medicating with ivermectin, an anti-parasite drug for animals that some falsely claim treats COVID-19.

According to the National Poison Data System (NPDS), which collects information from the nation's 55 poison control centers, there was a 245% jump in reported exposure cases from July to August — from 133 to 459.

Meanwhile, emergency rooms across the country are treating more patients who have taken the drug, after being persuaded by false and misleading information spread on the internet, by talk show hosts and by political leaders. Most patients are overdosing on a version of the drug that is formulated to treat parasites in cows and horses.

The troubling trend has been on the rise since the start of 2021 — despite warnings from state health officials and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention against taking ivermectin. The NPDS says 1,143 ivermectin exposure cases were reported between Jan. 1 and Aug. 31. That marks an increase of 163% over the same period last year.

Ivermectin was discovered in 1975 and is approved for use in humans to treat infections caused by some parasitic worms, head lice and skin conditions such as rosacea. When taken in appropriate, prescribed doses, it can be highly effective and is included in the World Health Organization's list of essential medicines.

But after some clinical trials at the start of the coronavirus pandemic, the Food and Drug Administration says the "currently available data do not show ivermectin is effective against COVID-19."

Exposure cases are spiking across the country

In Kansas, the Department of Health and Environment is urging residents to disregard false information about ivermectin's effectiveness against COVID-19.

"Kansans should avoid taking medications that are intended for animals and should only take ivermectin as prescribed by their physician," Lee Norman, secretary of the department, said earlier this week.

In Mississippi, which has one of the lowest rates of vaccination against the coronavirus, the state Department of Health issued an alert about the surge in calls to poison control in August. The department said that at least 70% of recent calls to the state poison control center were related to people who ingested a version of the drug meant for livestock.

Minnesota's Poison Control System is dealing with the same problem. According to the department, only one ivermectin exposure case was reported in July, but in August, the figure jumped to nine. Kentucky has seen similar increases. Thirteen misuse calls have been reported this year, Ashley Webb, director of the Kentucky Poison Control Center, told the Louisville Courier-Journal.

"Of the calls, 75% were from people who bought ivermectin from a feed store or farm supply store and treated themselves with the animal product," Webb said. The other 25% were people who had a prescription, she added.

"You are not a horse. You are not a cow. Seriously, y'all. Stop it," the FDA said in a renewed warning late last month.

Those with a prescription from a health care provider should only fill it "through a legitimate source such as a pharmacy, and take it exactly as prescribed," the agency instructs. It also cautioned that large doses of the drug are "dangerous and can cause serious harm" and said that doses of ivermectin produced for animals could contain ingredients harmful to humans.

The agency added: "Even the levels of ivermectin for approved human uses can interact with other medications, like blood-thinners. You can also overdose on ivermectin, which can cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, hypotension (low blood pressure), allergic reactions (itching and hives), dizziness, ataxia (problems with balance), seizures, coma and even death."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.