Section Branding

Header Content

Family Ordeal Catapults A Young Filipina To The U.S. — And The Pandemic Front Lines

Primary Content

If there is such a thing as a model citizen, Quimberly "Kym" Villamer might qualify.

She's a dynamo in a five-foot-one-inch frame.

"Excited," she says, to vote in her first U.S. presidential election, Villamer is part of the huge diaspora from the Philippines who have moved abroad for a chance at a more prosperous life.

Villamer had been a U.S. citizen for just a matter of months when, as a staff nurse at New York-Presbyterian Queens Hospital, she handled one of its first COVID-19 cases.

Shortly afterward she was tapped to manage the New York City hospital's nursing staff while being called to serve on the front lines herself.

Successive generations of Filipinos have pulled each other along to the United States, bound by a shared culture and history, and economic opportunity. The Villamer family migration personifies that Philippine national dream which seems to reach an apex in young Kym Villamer's against-the-odds story. But for the doggedness of parents and the grit of their young girl, it may never have happened.

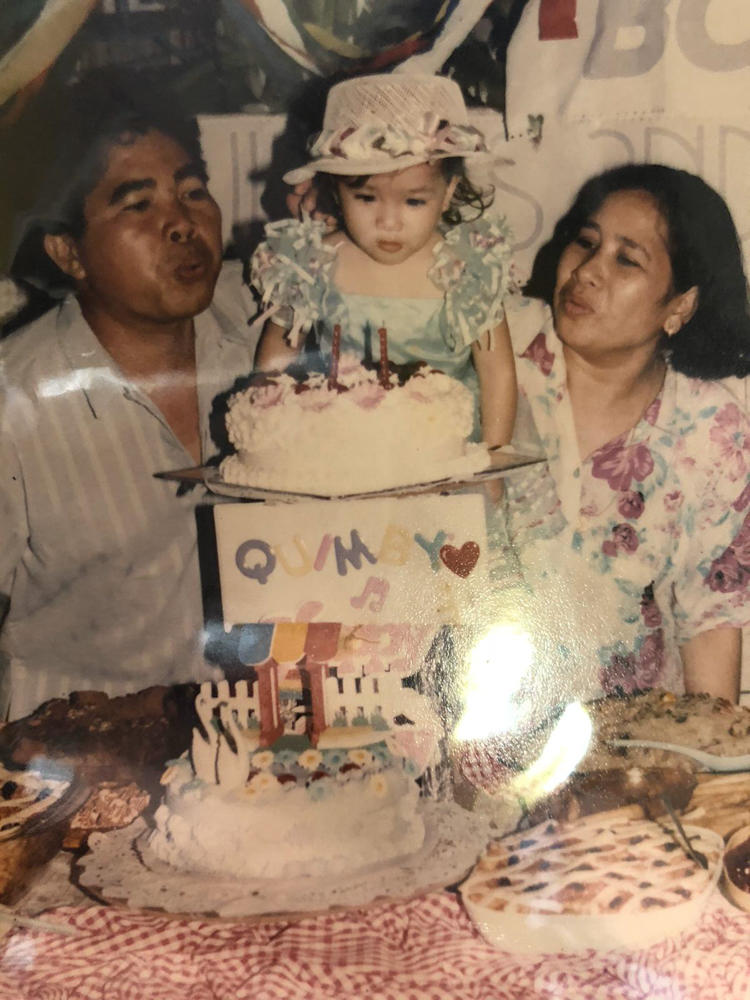

A tumultuous personal journey brought Villamer to New York City to care for the sick and dying. Villamer, 29, recalls her childhood upended.

In 2001, her parents left Villamer, their youngest of seven children, for the United States.

The couple departed their home in Iriga City in the central Philippine region of Bicol when she was just ten years old. The eldest, a sister in real estate living in North Carolina with her American husband, petitioned for her parents, Baldomero and Bernadette Villamer, to join them, and they did.

Villamer says her parents were solid members of the middle class in the Philippines, but sought to "give [their children] the opportunity," for betterment in the United States. They were committed to becoming naturalized U.S. citizens and subsequently petitioning for their six of seven children to come to America.

A 15-year gap separates Kym Villamer from her siblings, and as the youngest child, she felt the brunt of their parents' migration keenest.

"Before that, I was sleeping with them in their bedroom. We would pray together before bedtime. And that time, I was devastated to see them leave," she told NPR. As she recollects the separation, Villamer's voice catches with emotion as she confides: "Until this moment it was one of the saddest moments of my life."

This was not a case of abandonment. The Villamers fought to have their daughter accompany them to the States, but she says her mother gave birth to her late, in her 40s. Her father was older, and officials at the U.S. embassy were suspicious that she might not be theirs.

Villamer remembers tearful scenes at the embassy begging to be allowed to go. "I think they doubted that I was a legitimate daughter," she says. Her parents made brief visits back home for special school occasions, but Villamer says nearly a decade would pass before she could be reunited with them in the States.

Villamer's parents eventually settled in San Leandro, a suburban town in Alameda County, Calif. The pair performed all manner of menial jobs to earn money to send home. For many years, Baldomero Villamer was a custodian at a local public school.

During the long parentless period, one of Villamer's six siblings, a 26-year-old sister, took Villamer in. Her parents provided the financial support for their young daughter.

But Villamer says her parents kept their word to call "every day," and sent home trendy tennis shoes and clothes like "the Spice Girls wore." A young daughter pining for her parents came to understand the trade-off: "That it was a difficult decision they had to make to provide a better future for our family ... Now that I'm older it's one of the best decisions that they made."

But relations between the two sisters deteriorated and Villamer found herself trying to escape a home that she described as increasingly volatile — and a sister who she says grew increasingly "abusive."

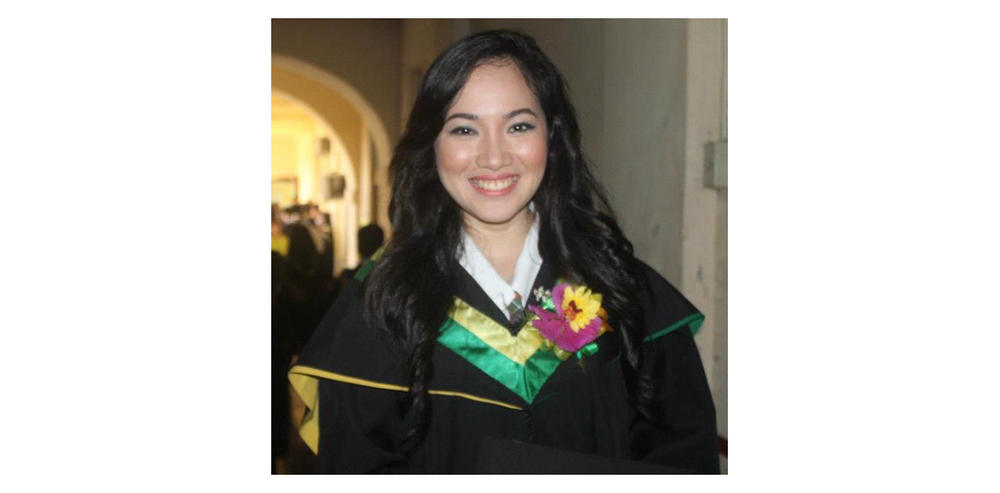

Villamer, a young teen by then, decides she is better off on her own, and comes into her own at the Universidad de Sta. Isabel, the oldest school for girls in Southeast Asia. A private Catholic university in Naga City, not far from Villamer's hometown, it runs from high school through post-graduate studies.

With her parents' permission, she moved off campus and skipped the obligatory 6:00 a.m. daily mass, arguing it was "too early." She says the nuns called the 14 year old "an old soul" with survival instincts who became an inveterate joiner.

"I joined the debate team. I joined the Young Writers Club. I was a dancer. I was a singer." Villamer says she did not feel "wounded" by all that had happened to her, but rather she was animated by the desire to "survive," "grow," and surpass family expectations.

The nuns who administered the school noticed her intelligence and potential, and took the girl, whose parents toiled thousands of miles away, under their wing.

Villamer was a champion debater, where she won accolades from the nuns and tournaments for the school's debate team, which she coached well into her college years.

Naturally, Villamer says she had envisioned a career in law upon graduating from high school.

But her mother, who worked three jobs, including as a parking lot attendant to send money home from the U.S., vetoed that career path.

"Suddenly Mom said, 'You're going to be a nurse. It's your passport to the American dream,' " she says. Her mom thought it if she became a nurse, she could land a good job in the U.S. "She actually threatened me: 'I'm not going to pay for your college if you don't become a nurse,' she told me. I said 'Okay, fine!' " Villamer explains, laughing.

She picked up her studies at her alma mater St. Isabel, won a scholarship, and — overcoming "a fear of blood" — earned a degree in a profession she says is now her passion.

"Who can't fall in love with a profession that allows you to spend so much time with these patients in the darkest of their days; to be able to be their voice when they can't speak for themselves; and to also spend the last moments of their life when their family's not around. Who can't fall in love with a profession as beautiful as that?" Villamer says.

Villamer's mother suffered a stroke in 2008 and stopped working. A year later, the couple's California home was foreclosed on following the collapse of the real estate market in the Great Recession of 2008.

But there was an upside: In 2009, when she was 18 and still a minor, Villamer was cleared to join her parents in the United States. They got an apartment where they briefly lived with their daughter before she returned to the Philippines to pursue her nursing studies, considering education in United States too expensive.

The personal cost had been high. But by 2013, when Villamer graduated, her parents' mission of having a nurse for a daughter in the U.S. was complete. And the couple continued to petition for their remaining adult children to come to the United States.

Sixteen years after arriving in the States, in 2017, Villamer's parents retired to the Philippines.

Their daughter, who places great store in diversity, headed to New York City, a place where she was certain to be welcomed. "To be able to come here and not forget about my identity and find out that, 'Oh, wow ... New York celebrates the difference that I bring to the city."

Embracing her new hometown, Villamer ran the New York City Marathon in 2018, modesty adding that it took "seven hours."

The coronavirus is relatively under control at present in New York City. But Villamer recalled the staggering surge in the early months of the pandemic when refrigerated trucks served as morgues, and hospitals overflowed with the sick and dying.

"I've never seen so many sick people. I had to step out, cry five minutes and then come back," she says.

Risking their lives, the front liners of New York-Presbyterian Queens Hospital have saved more than 2,000 COVID-19 patients who recovered and walked out. Villamer says for her, walking into a patient's room was enough to conquer the fear of the virus.

"You forget. You forget about COVID. And all you see are just human beings who need you. So it's not scary. It's just someone's dad, someone's mom, someone's loved one who needs you," she says.

The Philippines is the leading exporter of nurses in the world. These health care professionals are considered one of the most successful segments of the country's sprawling overseas workforce. Villamer is among 150,000 of her compatriots who earned a nursing degree in the Philippines and are now practicing in the United States. She says being steeped in Philippine culture may be the secret to their success beside a sickbed.

"We are a caring bunch. I cry with my patients. I celebrate their victories. I think about them when I'm home. You know, opening your heart out for people," she says.

The coronavirus is taking an outsized toll on Filipino American nurses, and Villamer says she does worry about the Filipino nurses who staff intensive care units. One in every four Filipinos in the New York-New Jersey area is employed in the health care industry — and because of their profession, are falling ill at higher rates than other ethnicities.

Villamer says COVID-19 tests each of us, and she evinces the optimism of a new citizen in her conviction that the United States can defeat it by doing what it has historically done facing great adversity. "Regardless of our differences, we've got to be there for one another," she says. "It's what the world needs at the moment. So you are being a light to the world."

Villamer tapped a network of former classmates and raised money and materials for fellow front liners badly in need of personal protective equipment in the Philippines. She does charity work for children, most recently providing toys for kids in the Philippines.

"I recognize the fact that it's not easy for the people I left behind," she says.

As a way to uplift people around her, Villamer likes to sing.

The New York Presbyterian Queens Hospital shared a video of her masked up and crooning alongside a colleague, belting out crowd-pleasers to hearten stressed patients and staff.

A version of "Ain't No Mountain High Enough" rouses masked colleagues to their feet and gets them dancing and singing around the nurses' station, celebrating the mini concerts, which have become a welcome ritual as the months of the pandemic rolled on.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.