Section Branding

Header Content

From Syria To America: A Teen Seeks A 'Safe Place' In The Universe

Primary Content

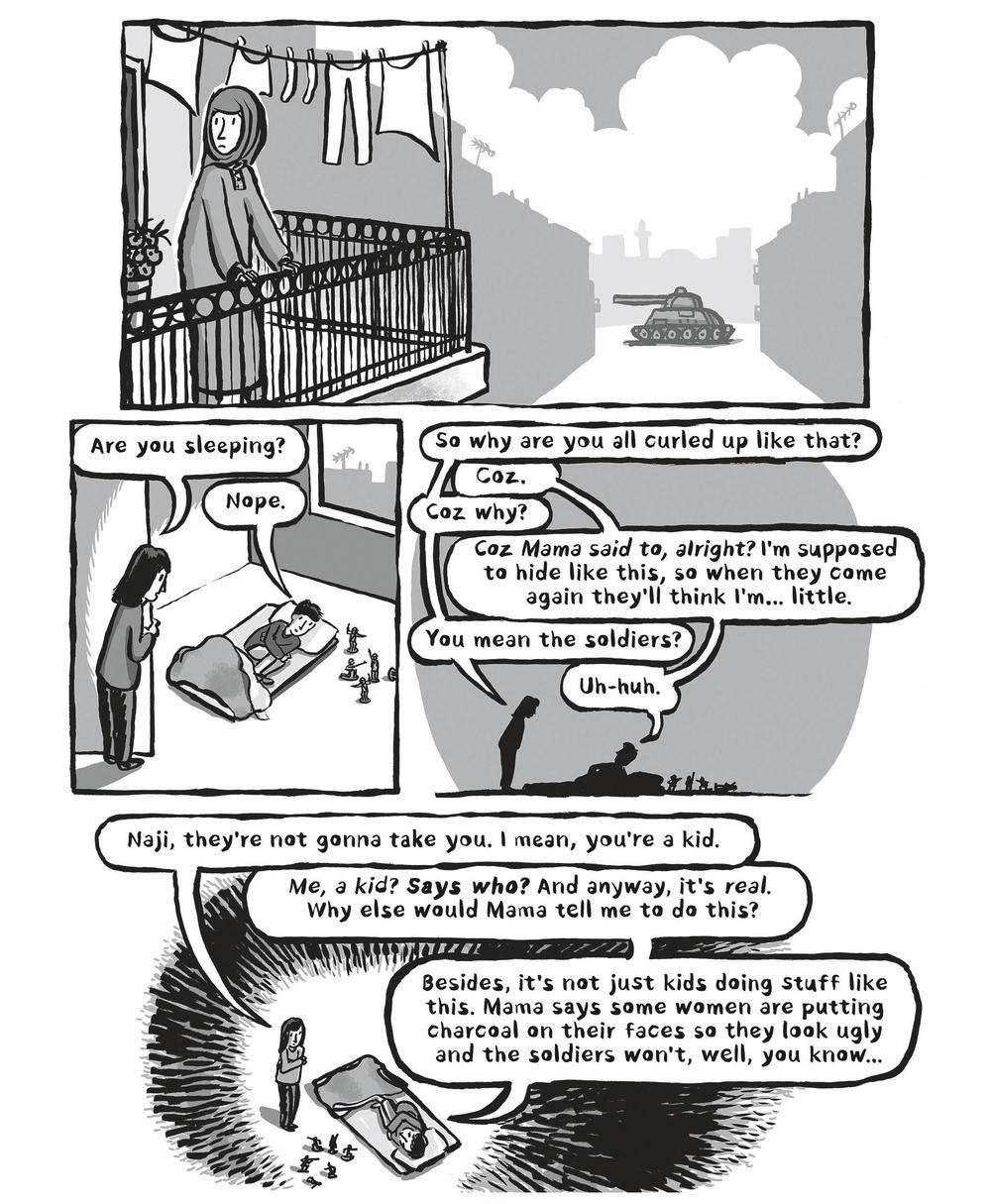

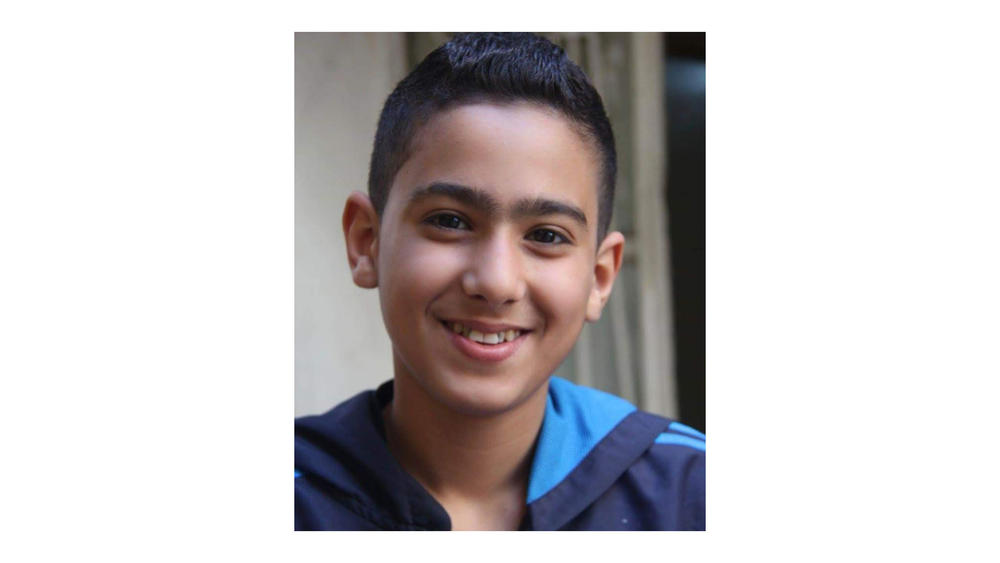

The last time Naji Aldabaan remembers feeling like a kid — mainly concerned with whether his mom would make him do homework or let him outside to play soccer — he was 10 years old.

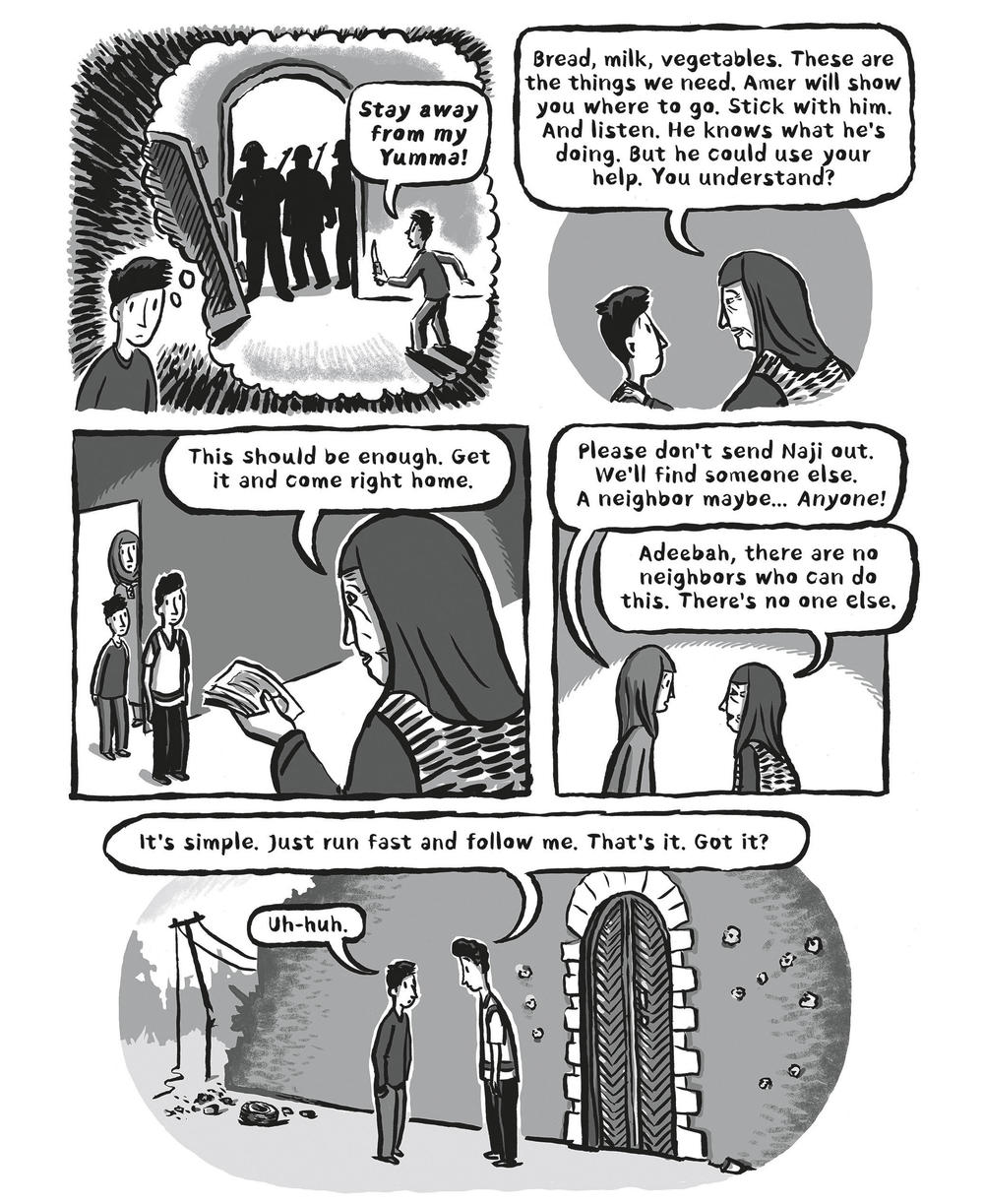

The year was 2011, and Syria was collapsing into civil war as nationwide protests against the government were followed by crackdowns and arrests. One day, soldiers knocked on his door. They had taken away Naji's uncles. Now they'd come for his father. No one knew why. Such was the random nature of the terror.

Reporter Jake Halpern, who chronicled Naji's story with artist Michael Sloan in a Pulitzer prize-winning series for the New York Times, was interested in telling the experience of a Syrian refugee family through the eyes of a young adult. Halpern is the co-author of several young adult novels, adventure stories where kids are left to their own resources to save themselves (and sometimes the world as well). In his books, Halpern says, "the veneer of childhood falls away, [along with] this idea that life is good and society is there and parents are there. The kids are left to fend for themselves and figure it out for themselves."

For example, in Nightfall, co-authored with Peter Kujawinski, three kids find themselves abandoned on an island and have to escape the island before monsters find them first.

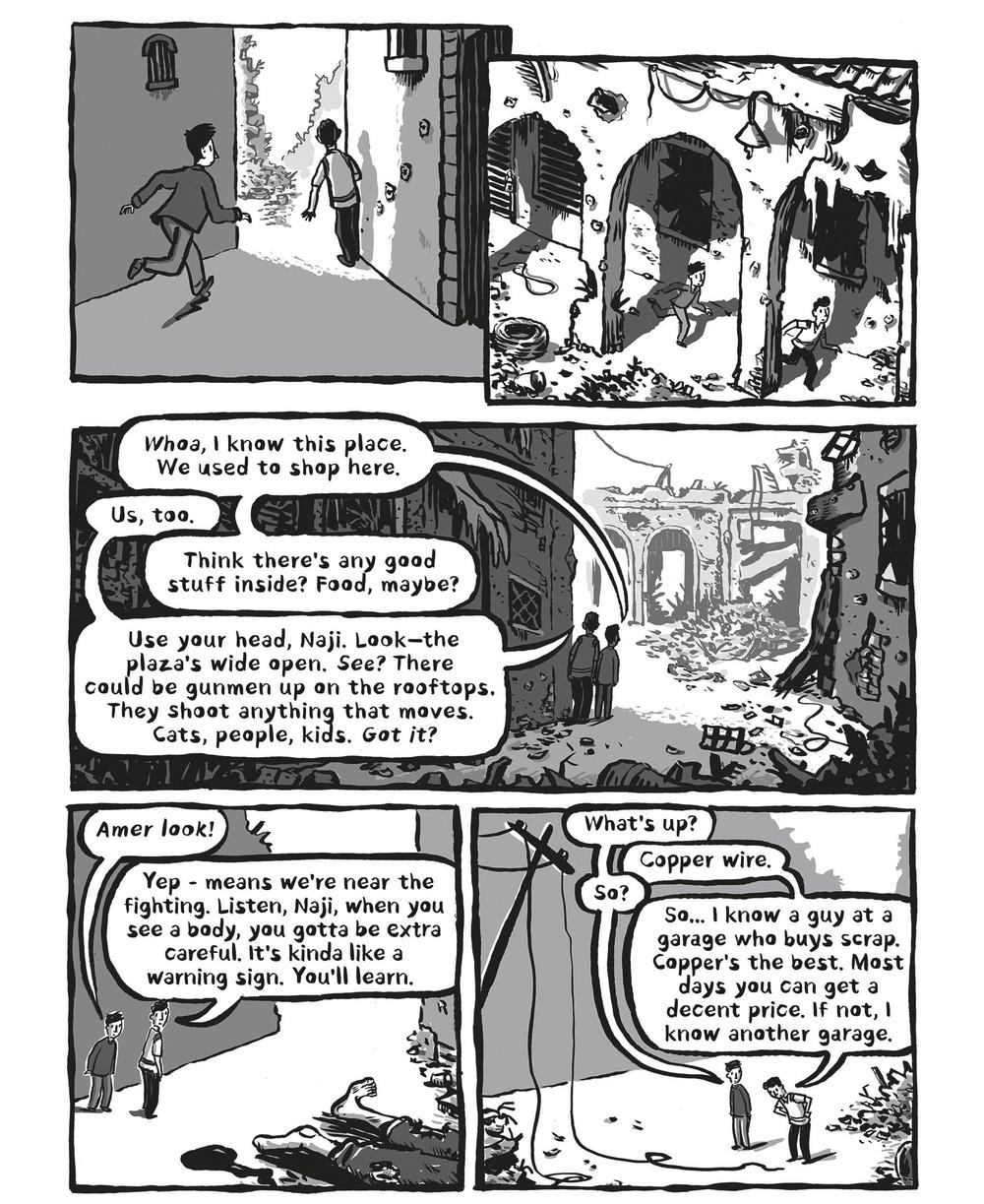

Indeed, many novels written for young adults are stories of kids who battle threats without parental protection. Naji, in Syria, almost seemed like one of these heroic characters — a child left to fend for himself in a hostile world.

But there was one important difference between Halpern's adventure novels and Naji's real-life war story. His father did not stay missing. After 40 days in prison, he and Naji's uncles at last come home. Naji remembers that day of his father's homecoming, how he threw himself into his father's arms and wept. He felt as if a burden had been lifted.

"I'd been through so much, that when I saw my dad, I felt like, you know, I'm safe again," Naji said. "Like you're in the middle of the ocean, and suddenly there's a boat."

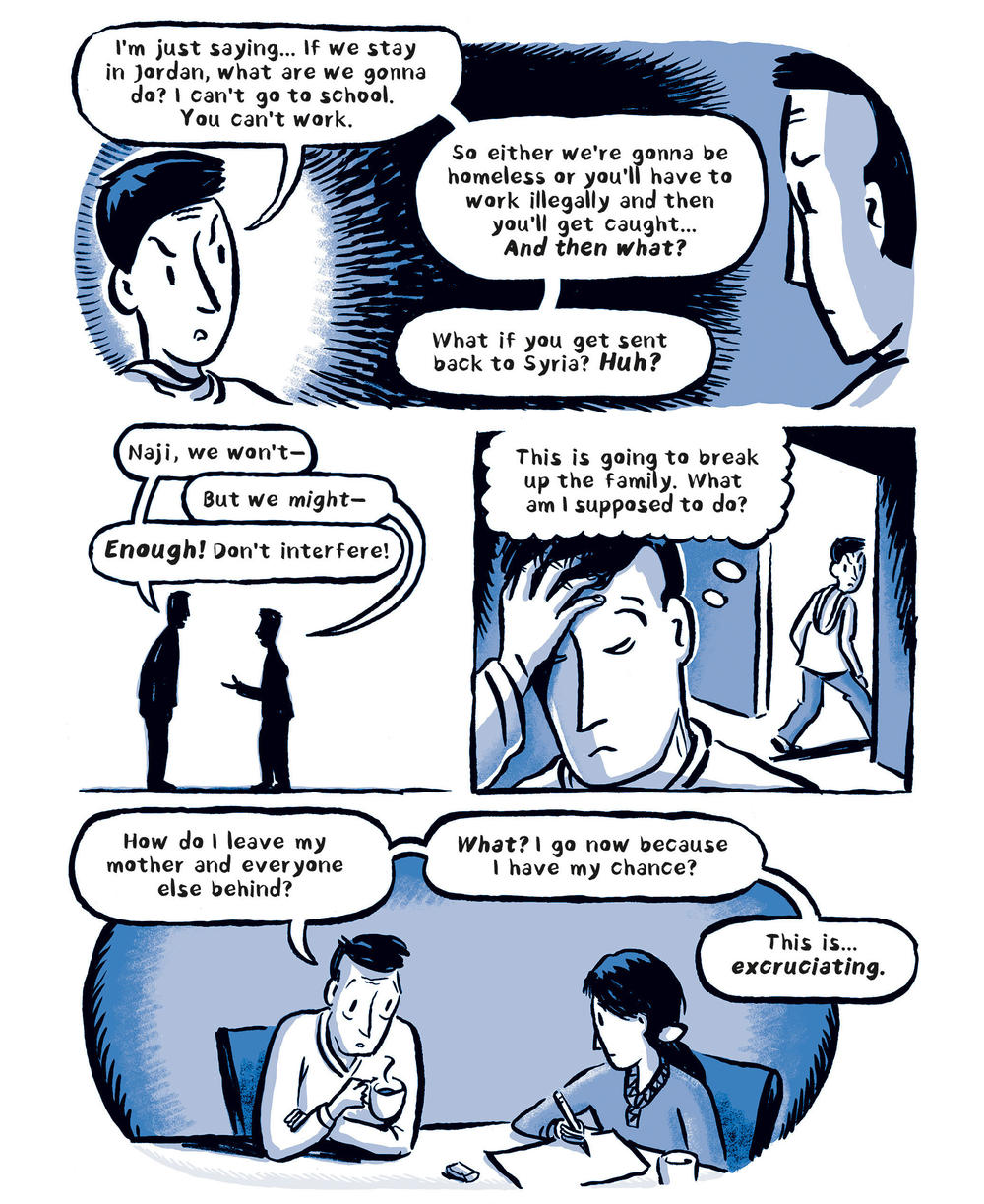

The sense of relief that Naji felt in that moment — the feeling that he was relieved of his premature role as the family's protector — was not to last. His father's return did not restore the lightheartedness of childhood. If anything, Naji felt even more responsible for steering the family to safety, even when that meant challenging his father's authority. As a refugee in Jordan, Naji pressured his father to take the family to America, though it would mean leaving their extended family behind.

Naji's family did seek a better life in the U.S. But not long after they arrived in 2016, they got a death threat on their voicemail — "America is only for white people... you have 24 hours to leave the United States or I will chop your head off." Ibrahim, the dad, called their co-sponsor, who called the police, who called in the FBI. They were taking it very seriously. But Naji still felt that he needed to do more.

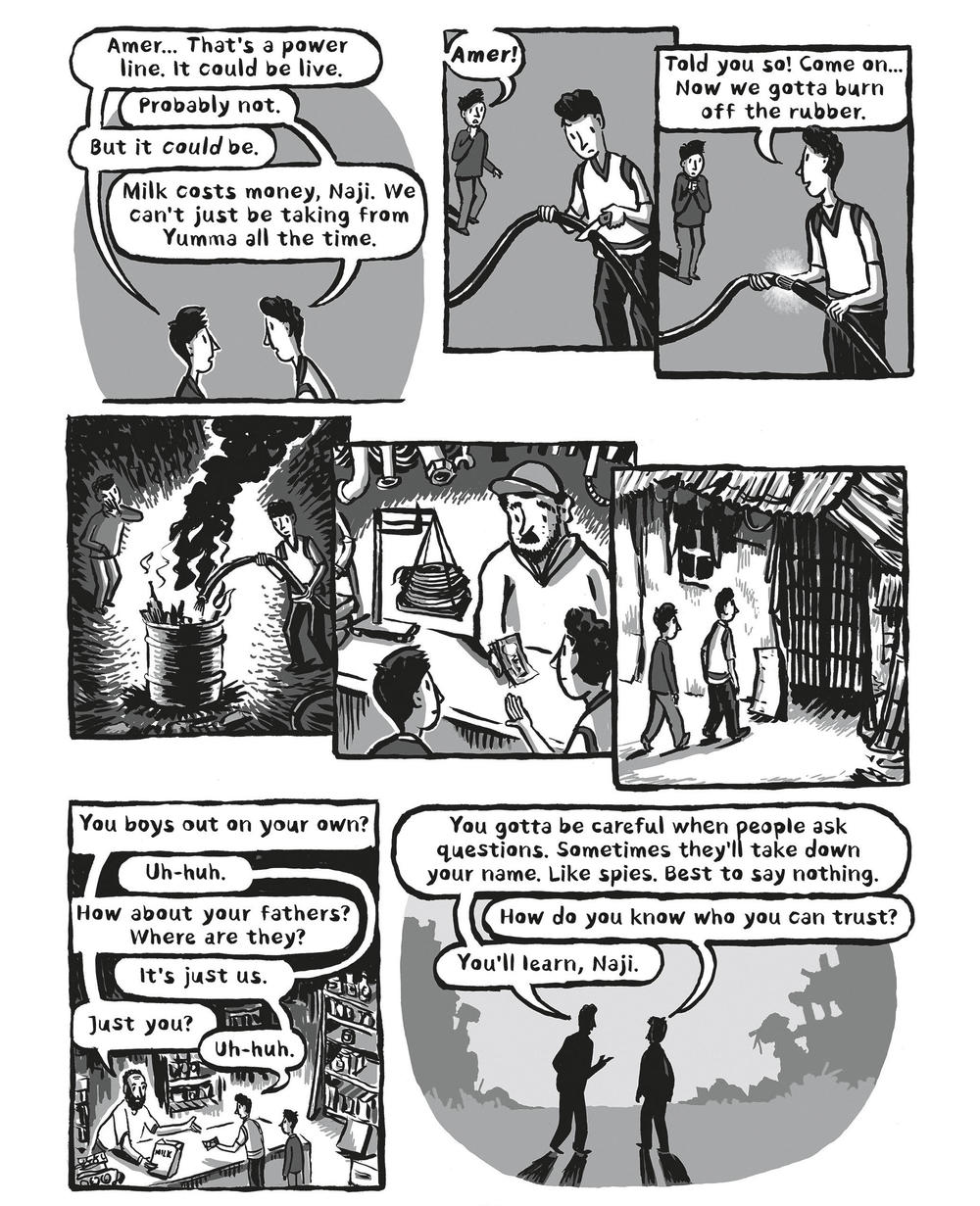

Throughout the series by Halpern and Sloan — now released as a graphic novel called Welcome To The New World -- we watch Naji attempting to resolve his desire to be a kid again, with his need to step in as the family protector.

The teenager admits to Halpern that when they came to America, he hoped to reclaim some of his lost childhood years. "To do the things I missed when I was younger," he says. "Play outside, have toys, think like a kid again." But he couldn't hope to find that carefreeness of childhood until the whole family felt safe. And what if seeking that safety meant Naji continually had to thrust himself into the role of decision-making adult?

In an interview with NPR's Rough Translation, Halpern recalled an early lesson he learned about writing in the young adult adventure genre. He had just turned in a draft of Nightfall, the novel about the kids trying to escape the island with the monsters. In the last scene in that early draft, a lone adult figure — the father of one of the kids — was coming back across a bridge to rescue them.

Their editor at Putnam, Ari Lewin, told them, in no uncertain terms: Cut the dad.

"I know why you guys put it in there," Halpern recalls her saying. "You're dads, and you like the idea that you come back for your kids. But no."

They had broken a major rule of writing this genre.

"The rule that we broke was that the parent to some extent came back and helped them achieve the last part of their escape from this island," Halpern says. "And therefore deprived the kids of succeeding entirely on their own power and by their own agency. That's one of the things that this genre is delivering big-time."

There's a psychological truth here. If you're a kid and you realize the world is unsafe, it is very hard to unrealize that. It's certainly not as easy as just having a parent show up and then you think, "Oh great, things are back to normal." In a novel, you have to take that truth to its psychological conclusion. You have to have the kid — the hero of the story — make it through to the other side on their own.

In the real-life story of Naji and his family, Naji tries to find this happy ending with his family by his side. From Syria to Jordan to America, he's hoping to find a place where they can feel safe. Then he can feel like a kid again. In the end, he never finds that haven. But he also doesn't fail in the journey. Instead, he realizes: "there is no safe place in the universe." Now 19, he settles for smaller moments of joy — moments where, despite everything, he can experience life as any teenager might.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.