Section Branding

Header Content

Coronavirus FAQs: Are Playgrounds Too Risky? Do I Need A Mask For Outdoor Exercise?

Primary Content

Each week, we answer "frequently asked questions" about life during the coronavirus crisis. If you have a question you'd like us to consider for a future post, email us at goatsandsoda@npr.org with the subject line: "Weekly Coronavirus Questions."

After a long and toilsome week of Fortnite and family flicks, beleaguered parents of young children might well see a trip to the playground as a needed reprieve.

The benefits seem obvious enough: Catch some precious outdoor time while turning your child loose on swings and slides to the point of exhaustion — bringing the week to a tranquil close. Ahh. (Sigh of relief).

Yet with COVID-19 in play (no pun intended) it's not always so simple.

This week, L.A. closed down its playgrounds for the second time, drawing furor from parents. And across the country, at least 16 states have done the same since the start of the pandemic.

With the specter of an ever-increasing infection count, it's fair to wonder, are playgrounds really a good idea right now?

According to Harvard Medical School physician Abraar Karan, if you're prudent, a playground trip is actually a great idea.

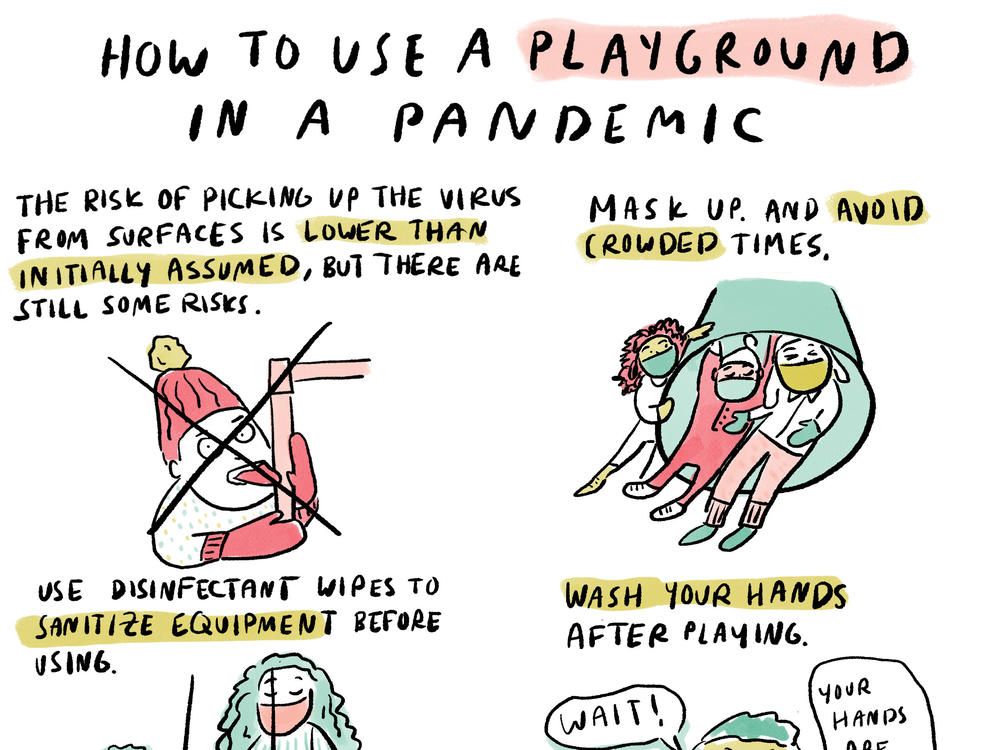

The first thing to note is that the risks of picking up the virus from surfaces — so in the context of playgrounds, think: jungle gyms, rock walls, slides and swings — are lower than initially assumed.

We know this thanks to breakthroughs in COVID-19 fomite research. A fomite is any object or particle that is covered with virus particles, possibly because someone recently sneezed or coughed respiratory droplets onto it. Fomites can include utensils, clothing ... and sliding boards ... says Sonali Advani, an assistant professor of medicine at Duke University.

If you touch a fomite, then bring your hands to your mouth, nose or eyes, you could become infected.

Even though there was concern early in the pandemic about this possible mode of transmission, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in May that surfaces are "not the main way" the coronavirus spreads. Successive studies have fortified that belief.

Still, Advani says, while the risk of transmission from surfaces is low, "it is not absent."

What does this mean for playgrounds?

Well, Karan explains, since fomites, epidemiologically, are not a huge source of viral transfer, it's probably not likely that children will pick up the virus and later infect themselves while careening down a slide or monkeying around on the monkey bars. The bigger risk is respiratory transmission— so it's critical you follow some of the general guidelines: masking, sanitizing hands after visiting, and physical distancing while on the scene.

"Outdoor playgrounds do have the benefit of being outdoors, of being able to space children out," Advani says. Outdoor airflow disrupts the flow of droplets and airborne particles. "But if everyone goes to the playground, it's going to get crowded."

As an extra precaution, Advani advises practicing situational awareness: If there are a lot of families at the playground when you arrive, try coming back in a few hours. And carry along a set of disinfectant wipes with you, wiping down surfaces before your kid gets on them — just to be extra safe!

The last stage of a safe and successful playground trip in the age of COVID-19 is the cleanup.

"Washing your clothes isn't a bad idea [once you arrive home], Advani says. "It's not that hard to do, and you'll probably want to do it in any case." Even though the risk that your garb was contaminated by contact with fomites is low, it's better to be safe.

And don't forget to wash hands after a visit with soap and water. You can keep the playground spirit going by singing the alphabet song to make sure you hit the 20-to-30 second mark.

What should we make of the WHO's guidelines on no-masking while doing exercise?

This week, the World Health Organization released a controversial statement: masks shouldn't be worn during "vigorous intensity physical activity."

The message was intended to tighten guidelines the organization laid out in June, when WHO released an infographic detailing why it may be a bad idea to wear masks while exercising.

During vigorous activity, the WHO says, "sweat can make the mask become ... wet" — which, the agency went on to say, can lead to bacterial growth on masks, and impede breathing ability.

Experts don't all agree with WHO's approach, and many flat-out rebuke it. So it can be hard to figure out what to do.

Indeed, the experts we spoke to say that while it has been well documented that the risk of non-masked outdoor exercise is pretty low, there can be important symbolic and public health advantages to having a mask on you. In deciding what to do, you should come up with a strategy that gives you options to tailor your approach to your environment, your perceived risk levels and other factors.

"Walking around, wearing a mask shows respect and it sends the message that you believe masking is important," Karan explains. "And the downside of masks is minimal."

In general, Karan says, it's fine to exercise with a mask on. And as long as you're washing your mask after a workout, you can ensure there's not a constant buildup of bacteria. He adds that there's been no large body of data to suggest that bacteria buildup has caused any medical issues.

But Advani acknowledges that it can be hard to mask while engaging in high-intensity exercise, simply on a breathing level. She proposes a solution: Carry a mask with you, and at traffic lights or stretches in the run where you may be around others, put it on if you feel inclined.

"It's not necessary to do while running [without anyone around], but having one on hand will always be helpful."

One other component of the WHO's brief stated that if distancing and ventilation are well-managed in a gym, it's OK to take off a mask while working out in that setting. To that point, both experts interviewed for this FAQ stressed that it's preferable to keep your exercise outdoors, where it's more difficult for the virus to spread.

Pranav Baskar is a freelance journalist who regularly answers coronavirus FAQs for NPR.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.