Section Branding

Header Content

WHO Film Festival: Starring Matchsticks As Burnt Out Health Workers

Primary Content

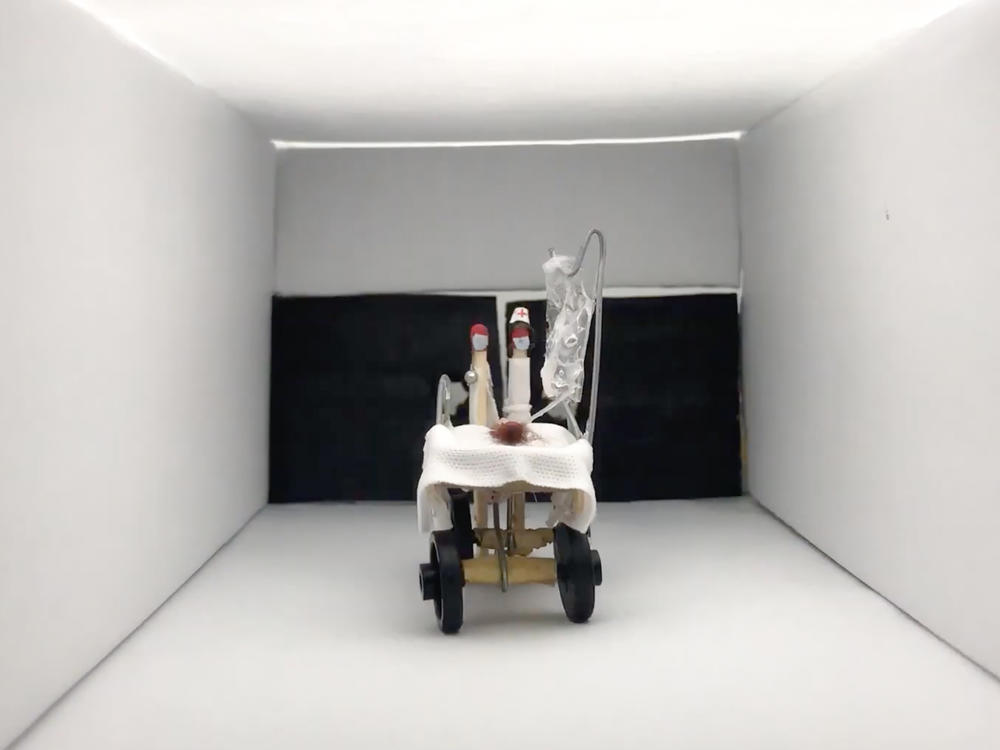

The primary film set of the El Salvadoran stop-motion animation film "Phosphôros" is a barebones, shoebox-sized COVID-19 care ward fashioned roughly out of bits of cardboard and fabric scraps. The nurses are "played" by matchsticks dressed up like dolls.

Don't be fooled by their diminutive stature: These inches-tall splinters of wood and phosphorus can act.

In two wordless minutes the film encapsulates one of the most familiar tragedies of the coronavirus pandemic: A nurse tends to her intubated patients around the clock. The patients get better, give thanks and go home — but by then the nurse has contracted their disease.

As folks outside the hospital carry on with their socially-distanced lives, the nurse's condition worsens until her lifeless body is draped in a white sheet. In the bittersweet final scene, a couple exchanges a kiss on a playground bench and turns to watch the sunset as their child spins on a merry-go-round nearby. Life goes on, but the world will never be the same.

"Phosphôros" is one of 56 finalists in the Health for All Film Festival. The competition, hosted by the World Health Organization, is open to (very) short films (8 minutes max) that feature global health problems deserving of greater attention and resources as well as possible solutions. The pandemic is one of the many topics.

Now in its second year, the competition received nearly 1,200 entries from independent filmmakers from 110 countries. Winners will be announced on May 13. All the films on the shortlist are now available to watch online for free. Members of the public are invited to share their reactions and pose questions to the filmmakers on each film's YouTube page. Remarks left before May 10 may be used during the festival's online awards ceremony.

"Break the silence" is one of the films highlighting a community-led initiative. It follows members of the Rhada Paudel Foundation as they travel across Nepal to dismantle the 40 types of restrictions still widely imposed in that country on people who menstruate.

One of the primary hurdles is getting people to admit that limitations on mobility, food and touch during menstruation still exist, even in urban areas like the capital Kathmandu, when many Nepalis insist that such practices are a thing of the past. As one man says during a community meeting in the Bara district, "There is no such discrimination. They are just not allowed to cook food." In a later scene a woman says it's not a problem for students to miss a week of religious school during menstruation because "they wouldn't be able to touch the pencils and books" anyway. Paudel presses people of all castes, classes, regions and religions until they become aware of the contradictions in their beliefs. Then her group provides education about biology and menstrual hygiene to challenge the persistent taboos and restrictive cultural practices.

Other films profile individuals on a personal quest. Vermont-based ultra-runner and author Mirna Valerio swims in a glacial lake, runs on rural roads and hikes along fern-lined wooded trails in "Running Through Barriers." She became an active outdoorswoman when intense chest pains brought on by a stressful job inspired her to spend more time outdoors to "get [her] health back." But, she says, she quickly found that because her "fat" physique isn't what people expect from an outdoor athlete, she's held up to constant scrutiny. And as a Black woman she constantly worries that she, or especially her Black son, could be "mistaken for someone with less-than-good intentions" while out on a trail. (Feeling unwelcome and unsafe in nature is a common experience for Black people and other people of color in this country). That's how she became an outspoken advocate for inclusivity in outdoor exercise. "I want to see that these spaces have opened up for everyone. And that people feel more comfortable, and that they feel entitled," she says. "Because we are entitled to be out in nature. We're humans, that's what we're supposed to do."

Other films depict collaborative models of change. A mysterious regional spike in chronic kidney disease among Central American agricultural laborers is probed in "Photovoice: the voice of those affected by Mesoamerican Nephropathy." The film follows the workers as they team up with medical researchers to unearth the unknown origins of the disease, depicting a model for academic research that views the members of an affected population as knowledgeable contributors rather than passive subjects.

Nearly half of the films submitted to the festival this year include themes related to the novel coronavirus. Some finalists call attention to the ripple effects caused by the efforts to contain the virus' spread. In "Kwa Muda" a Kenyan student returns home after his university is shuttered. His mother's salon has been forced to close, so he pushes jerrycans of water in a wheelbarrow to support his family and supply the clean water to his community that people need to wash their hands.

In the Portugese entry "Why" ("Porque") a young girl plays in a landscape desaturated of color, visualizing the psychological burden of social isolation on children, even as the film recognizes the necessity of physical distancing for the common good.

A grand prix, which comes with a $10,000 grant, will be awarded in each of three categories: universal health coverage, health emergencies and better health and well-being. The categories align with WHO's global goals for public health. Special prizes will also be awarded for student-produced films, educational films targeted towards youth, and health equity films.

The festival's entries will be evaluated by a jury composed of humanitarian activists, science journalists, critically-acclaimed filmmakers and WHO experts. Dr. Soumya Swaminathan, a WHO chief scientist and one of last year's jurors, said one criteria is whether or not the films showed a path forward, "or if not a solution, it's giving you some hope" — even inspiring the audience to take action.

Ilan Moss knows for a fact that short films — and this film festival in particular — can dramatically raise the profile of often-neglected health issues. Moss is the head of media and content at the Drugs for Neglected Disease initiative, the research and development nonprofit that produced one of last year's grand prix-winning films in partnership with the South African based production house Scholars and Gentlemen. That film, "A Doctor's Dream," follows Congolese doctor Victor Kande and his partners on their successful quest to develop a revolutionary new treatment for sleeping sickness. (The only treatments available before this one were sometimes more toxic than the disease, says Dr. Swaminathan).

Moss says that even within the global health community sleeping sickness gets little attention, but winning a top prize for the film garnered a new wave of awareness for the deadly disease. "When we released the film it moved people, but it was nothing compared to when this award happened," he said. His organization has been flooded with requests for screenings, and more doors have opened for future research funding. "Visibility helps in this world," he said. "And awards help get that visibility. You need to break through a lot of noise to be noticed."

To see which films will get the spotlight treatment this year, tune into the live-streamed awards ceremony on May 13 on WHO's YouTube channel.

Emily Vaughn is a freelance reporter and audio producer based in Washington, D.C. Her Twitter account is @emilyannevaughn

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.