Section Branding

Header Content

Ready, Set ... Think! Hackathon Aims To Kill Off Fake Health Rumors

Primary Content

A new drug makes teen girls collapse! And it's secretly a birth control pill, part of a plan to reduce the national population.

Those are some of the rumors that revolve around the treatments for life-threatening diseases.

Now imagine you have 24 hours to come up with a plan to discourage people from believing the rumors and encourage them to seek treatment.

That was the challenge at this spring's Hackathon, an international competition hosted by the Task Force for Global Health's Neglected Tropical Diseases Support Center. While the competition sounds very COVID-relevant, in this case, the event challenged participants to dispel misinformation surrounding diseases like leprosy, Dengue fever and schistosomiasis.

"Rumors and misinformation are threats to progress [against diseases] and are not a laughing matter. They cost lives," says Moses Katabarwa, a competition judge who works at the Carter Center's Uganda River Blindness program and has seen how misinformation prevents patients from taking life-saving treatments. "Well-proven ideas can be threatened unless we tackle [rumors] intelligently and wisely head-on."

Fourteen teams participated in the virtual event, composed of up to four students in any major and from any school. They included students from Emory University in Georgia, the University of Buea in Cameroon and Aix-Marseille University in France.

A panel of public health experts looked at the solutions to see how innovative — and practical — they might be.

The first-place team won $2,000 and the chance to present their ideas in November at the annual meeting of the Coalition for Operational Research on Neglected Tropical Diseases. Second place also earned the opportunity to present the solution at the meeting but no cash prize.

Here's what the top two came up with.

This pill pack is designed for you!

Getting people to take a pill to prevent elephantiasis is a matter of trust.

That's what the winning team in the Hackathon found out.

Elephantiasis is a horrible condition, typically triggered by a parasitic worm. (The disease that causes it is called lymphatic filariasis.) If afflicted, a person's limbs and genitalia swell. It's very, very painful. In Tanzania alone, more than 6 million people are affected.

Taking the drug albendazole can help kill the worms. So why wouldn't you take the pill?

Caroline Pane, a 20-year-old public health major at Boston University, and her three teammates analyzed a 2016 study where researchers recorded first-hand interviews with villagers in southeast Tanzania about why they did or did not accept treatment for the disease. Pane and the team recognized a recurring theme: The villagers didn't trust the health officials or the drugs they were giving out. As one woman in a village said: "We don't trust free drugs; they have been brought to finish us off."

Other rumors, as noted in another study, were that the drug could cause infertility.

The team's solution? Redesign the pill packaging to build trust and confidence among Tanzanian communities.

The students got the idea after watching an educational video on the mass distribution of the drug in Tanzania.

"[Health officials] take a big white bottle that's covered in scientific writing in English to a village and just hand out pills," Pane explains. "The writing is foreign to them; they don't understand what it says. I probably wouldn't take it either if I was them."

In another study about the treatment that the team reviewed, one interviewee said, "There is no sign [on the drug] that it is for mabusha or matende," the Swahili words for swollen scrotum and swollen limbs. "You have to trust in the government to swallow the tablets ... the program doesn't come with enough knowledge."

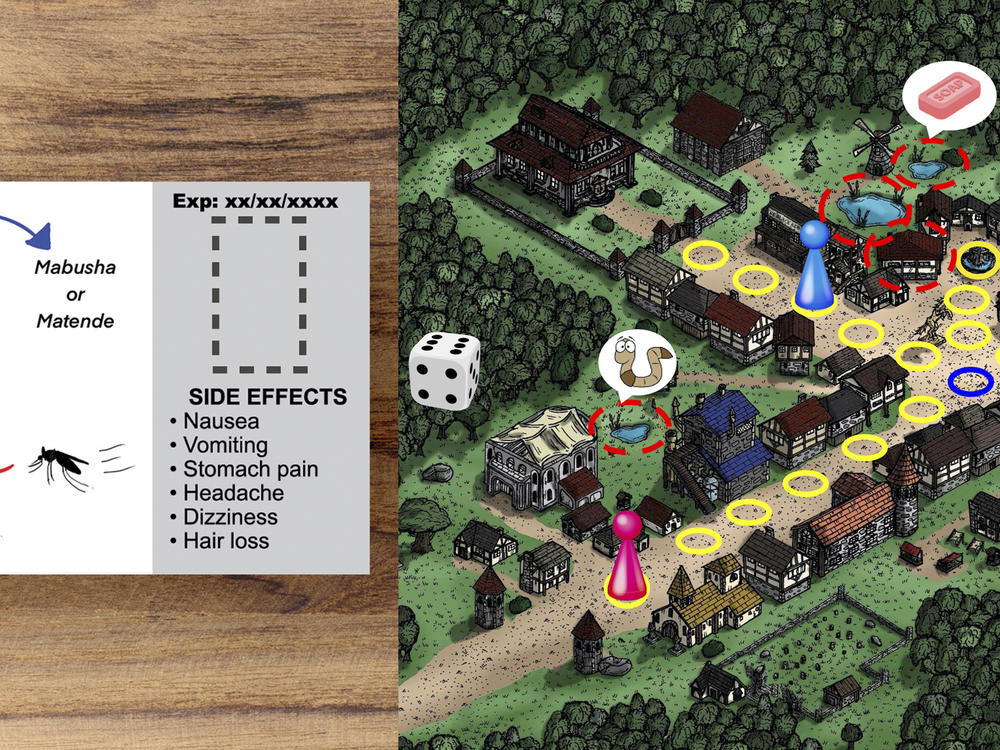

To quell these fears and build trust, the team designed and proposed a single-dose pill pack with information about the pill's purpose and side effects in Swahili.

The team also created a comic on the pill packaging to overcome any language barriers. The illustration shows how lymphatic filariasis spreads through the bite of a parasite-carrying mosquito, depicting a popular Tanzanian cartoon character who wears traditional African garb and jewelry catching the disease.

The team hoped that patients would be more willing to take the pill if they say a familiar character downing a dose.

Katie Gass, who helped design the Hackathon and is the director of research at the Neglected Tropical Diseases Support Center, thought the idea was excellent.

"People don't want a pill out of a random bottle dumped in their hand," she says. "This was a very simple, elegant and community-focused idea."

A rumor-finding tool — and a board game, too

To stop rumors in their tracks, the second place team decided to map them.

The rumors were about schistosomiasis, a parasitic disease prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions such as Africa, the Middle East and the Caribbean. The disease is spread through contact with water contaminated by parasite-carrying snails and can cause anemia, malnutrition and even organ damage.

"The rumors are not about the disease itself, but about the cures and preventions health officials are trying to implement," says team member Sina Sajjadi, 28, from the Complexity Science Hub in Vienna. "One that's popular [across regions] is, 'They're trying to test their drugs on us.' "

He was one of the four physics, computer science and math students on the team, from the Sharif University of Technology in Tehran, Iran and the Complexity Science Hub in Vienna.

Instead of focusing on a particular rumor surrounding the disease, the group proposed mapping where rumors are prevalent to identify regions that need further education about the disease and its treatment.

"We focused on where the rumors come from, like Facebook or Twitter," says team member Yasaman Asgari, 21, who attends the Sharif University of Technology in Tehran.

The team proposed creating a computer program to analyze online social media sentiments around treatments for schistosomiasis. The program would flag and map false claims using GPS data. Public health experts would then be able to pinpoint hot spots of misinformation – and create campaigns to address specific rumors. The team also suggested calling upon online influencers in the region to help dispel the falsehoods.

There's one more part to their plan: making a custom board game to teach children to be cautious around water sources such as ponds and streams, which could be infected with parasites. In regions with schistosomiasis, all freshwater is considered unsafe unless it's boiled, filtered or treated with chlorine.

"We would have different water sources on the board, as is the case for real-world villages," explains Sajjadi. The goal of the game is to avoid interacting with water contaminated with the worms.

While the students say they did not pull all-nighters to complete the 24-hour challenge, Gass wants to give the Iranian team a special shout out.

"Hats off," she says. They presented their work to the judges "when it was in the middle of the night for them."

Nadia Whitehead is a freelance journalist and science writer. Her work has appeared in Science, The Washington Post and NPR. Find her on Twitter @NadiaMacias.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.