Section Branding

Header Content

PHOTOS: The Hot-Spot Library Was Born In Two Shipping Containers In A Cape Town Slum

Primary Content

They call it the Hot-Spot library: a ramshackle building of plywood and sheet metal set on a crime-ridden street corner in Cape Town, South Africa. With its threadbare couches and mismatched carpets, the place looks somewhat dilapidated. On winter days, rain leaks through holes in the corrugated zinc roof and drips down onto the tables and bookshelves.

Built around a pair of aging shipping containers, it may not look like your conventional library. But for the residents of Scottsville, a neighborhood torn apart by drug abuse and gang violence, it offers a safe space to escape the harsh realities of daily life and to explore different worlds in the pages of thousands of donated second-hand books.

"For most of these kids, poverty, unemployment, the lack of good role models, that's the norm" says Terence Crowster, the Scottsville resident who founded the library in 2017 after appealing for donations on Facebook. "They wake up every day and put on this tough exterior, and they accept this kind of life as the norm. And what we wanted to do is to change that norm for them through reading books."

Crowster grew up with a mild speech impediment and was bullied by his classmates at school. Awkward and shy, he sought solace in the world of books and would often walk the 30 minutes from Scottsville to the nearest municipal library to pick up a copy of Asterix and Obelix or Tin Tin. For people growing up in Scottsville today, however, that library is effectively off limits, as the rise in gang violence has made the journey too dangerous.

The Hot Spot Library itself sits directly on the boundary between the territory of two rival gangs. This has made the immediate vicinity something of a battleground. Yet for the most part, Crowster says, the gangsters know that the library, which has the support of the local population, is off-limits.

"On this side it's the 28s gang," says Crowster, pointing down the street to the southwest. "And on this side it's the 27s. That's why we call it the Hot-Spot library."

He says the violence has been particularly bad in recent weeks, with frequent shoot-outs in the streets around the library. Just a week ago, he says, a teenager was stabbed in the neck just a few paces from the entrance, and a few days later a bullet slammed into the steel railings out front.

"You see that boy with the red mask" says Crowster, indicating a boy of 8 busy doing his homework with the help of a librarian at a nearby table. "His brother's just 12, and already he's a shooter in a gang. If you were to ask these kids how many of them had seen someone get killed, the answer would be all of them."

Initially based out of two donated three-by-six meter metal shipping containers, with books stacked in milk crates against the walls, the library had a membership of 30 in its first year. Today, it has over 700 members, including around 100 adults, and hosts more than 2,000 books, ranging from Afrikaans romantic novels to popular crime thrillers, modern classics and reference guides to local flora and fauna. Along the way it has been robbed twice, on one occasion losing electronics worth around $1,500, but has bounced back quickly on both occasions thanks to donations from the community.

What ultimately prompted Crowster to launch his project, he says, was visiting schools and witnessing firsthand South Africa's problem with literacy. While according to UNESCO, nearly 90%,of South Africans can read and write, this statistic obscures a worrying trend - the percentage of children who can "read for meaning" as opposed to simply being able to recognize words, is extremely low. The most recent data from an ongoing study by the University of Pretoria found that just 22% of grade 4 students could effectively read for meaning. The researchers said their findings highlighted a "crisis of reading literacy."

"It's a very bad situation," says Fadeela Davids, a literacy advocate who has been working on library and book projects in underprivileged parts of Cape Town since the 1970s. "There's no culture of reading in our schools. After grade 4, if you're one of the children who slipped through the gaps, it's likely you'll never be able to read."

Davids says much of the blame lies with an overburdened education system, with class sizes that are too large and teachers who are overworked. That, and a severe shortage of resources. And she argues that the COVID-19 outbreak has made matters even worse, disrupting reading and literacy programs run by nonprofits and limiting access to public libraries.

"A lot of children think that reading is a chore. They don't have a love for it because their teachers don't have time for it. We need to teach people to read for enjoyment," she says.

At the Hot-Spot Library, Crowster, who has a day job in the development sector, has implemented a system of book reviews to ensure that his young members are indeed reading for meaning. A borrower who returns a volume must fill out a review form, which the librarians – two local women paid a small stipend — store in old ring-binder folders.

"I like that Peter saves the people," wrote one reviewer after returning a copy of Peter Pan. "I don't like Captain Hook because he is rude with people." Such are the morals that Crowster hopes his young readers will internalize.

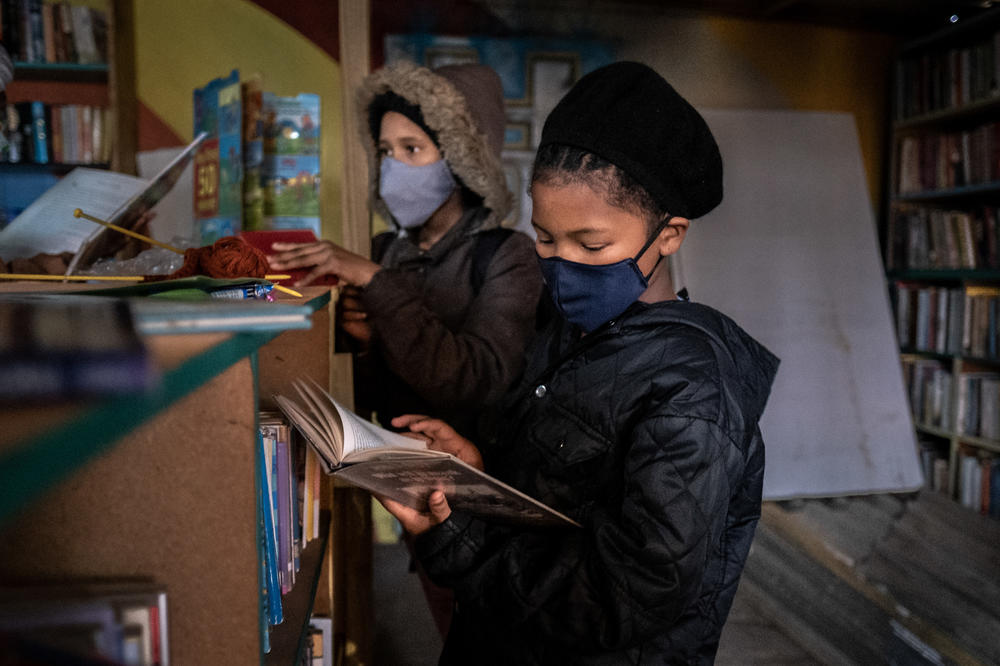

The library also hosts creative and educational programs, a different event each day of the week. On a recent weekday, a group of teenage girls were learning to knit, a cluster of younger children were making cards for Father's Day, and a volunteer from a recycling charity was showing another group of youngsters how to make keychains out of recycled yogurt cups.

"I was 7 years old when I started coming here," says 12-year-old Bernalee Victor, a daily visitor to the library, as she browses the bookshelves. Pausing, she picks out a copy of The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint Exupery, flicks through a few pages and then puts it back on the shelf, unimpressed. "It doesn't look very good," she announces, before continuing her search. Victor says the best thing she's read so far is a book version of High School Musical, mostly because of all the scenes with singing and dancing.

"I like reading, and most of my friends come here," she says, when asked why she enjoys the library so much. "And it's peaceful here. Out there people are always shooting."

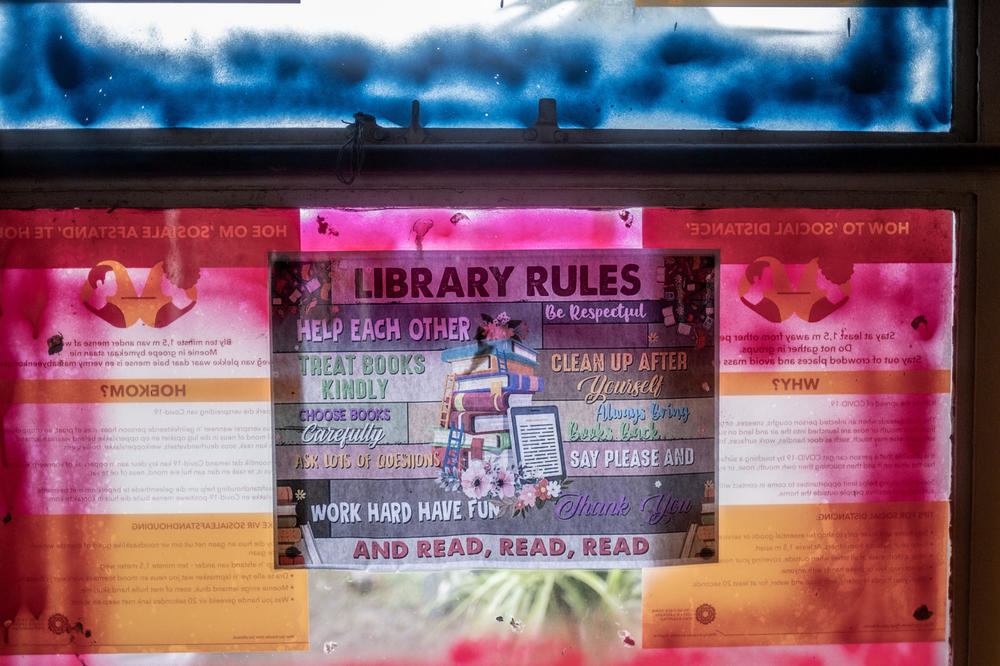

The library smells pleasantly of old paper, incense and dusty upholstery. Green plastic chairs sit in a circle in the main reading area next to a battered foosball table and irregular-shaped patches of worn out carpet don't quite cover the rough cement floor. Hardback books dangle from the unfinished wooden rafters by way of decoration. Art made by the library's members hangs on the walls alongside educational posters, guides for crafting an effective resumé and laminated sheets of A4 paper with book-themed quotes by Dr Seuss and others.

"Be Awesome! Be a book nut!" reads one. Another, typed out in rainbow letters above the reception counter reads: "Books aren't just made of words. They're also filled with places to visit and people to meet."

Librarian Abigail Cloete, who joined the library staff a few months ago, is among those who have found catharsis in reading.

"It takes me to a place in my mind where I can just relax and live in the book," says the 24-year-old. "Right now I'm in Hawaii," she jokes, pulling a small red copy of Heartbeat in Hawaii by Ena Murray out of her bag. "I like to feel the emotions. I like reading books that make me cry."

Encouraged by the popularity of the Hot-Spot Library, Crowster is planning to open a second venue in the coming weeks. Like in Scottsville, the new library in the nearby neighborhood of Scottsdene will also be based out of a shipping container and also sits in an area riven by gang conflict.

"The power of reading is that it increases your understanding of who you are and where you come from" says Sabelo Ngxola, a former gangster and Crowster's partner on the new library project. "It opens up your imagination."

During his gang days, Ngxola was shot on four separate occasions and stabbed twice before turning his life around, largely, he says, thanks to books. Once the library opens, he'll be responsible for managing the place when Crowster isn't around.

For now, the container in Scottsdene is empty but for a pile of cardboard boxes filled with books and a few scattered pieces of furniture. The container still bears gang graffiti on the outside as it awaits a fresh coat of paint, and the space behind it is piled high with trash. A building frequented by meth users sits just across the road. But Crowster is confident the second Hot-Spot Library will have the same success as his previous efforts.

"We want to create a safe haven where they can escape into another world", he says, as rain drips through a hole in the roof and collects in a puddle on the plywood floor, "where they can see themselves, and see what they can become."

Tommy Trenchard is an independent photojournalist based in Cape Town, South Africa. He has previously contributed photos and stories to NPR on the Mozambique cyclone of 2019, the Ebola outbreak and Indonesian death rituals.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.