Section Branding

Header Content

India Is The World's Biggest Vaccine Maker. Yet Only 4% Of Indians Are Vaccinated

Primary Content

MUMBAI – When Mumbai began lifting its coronavirus lockdown this month, Rekha Gala could finally reopen her late father's photocopy and stationary store, which she runs with her siblings in a jumble of low-slung businesses north of the city center.

They'd been closed for nearly three months. They needed to recoup business. But she was terrified. Gala had lost both her parents to other illnesses in the past year and several neighbors to COVID-19. She'd only been able to get her first vaccine dose, which she knew wouldn't fully protect her from getting ill.

So she strung a rope across her shop's open doorway. Customers point at merchandise through the front window, and Gala passes things to them across the rope. Even so, business is "not even 50%" of what it was before the pandemic, she says.

"Small businesses like ours, we're struggling to survive," Gala says. "But we also need to take precautions for ourselves – and take vaccines if we can get them."

On Tuesday, India confirmed 37,566 new coronavirus cases — less than a tenth of what it was seeing at its peak last month. As the country emerges from the world's biggest and deadliest COVID-19 outbreak, scientists and policy makers say vaccinations will be key to India's safety, confidence and economic recovery. Small business owners like Gala agree.

But so far, only about 4% of people in India are fully vaccinated. And scientists say another COVID-19 wave may hit India this fall.

The Government's Insufficient Order

That's a surprising position for the country that's home to the world's biggest vaccine manufacturer, the Serum Institute of India. It has long churned out more vaccine doses by volume than any other company, even before the coronavirus pandemic.

Last spring, Serum's CEO Adar Poonawalla made a gamble: He began mass-producing several COVID-19 vaccines even before clinical trials revealed which ones would work. He concentrated on one in particular – the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine. He knew it would be useful in low resource countries because it doesn't require ultra-cold refrigeration.

In late 2020, clinical trials yielded positive results. Countries around the world began granting emergency authorization to the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, and the World Health Organization followed suit. By then, the Serum Institute already had tens of millions of doses ready to distribute. Poonawalla promised half of his production to his home country of India.

Confident with that pledge from Serum, the Indian government set ambitious goals at the start of its COVID-19 vaccination campaign in January.

But it didn't order enough doses.

It wasn't until Jan. 11 — five days before India's national vaccination drive began – that the government ordered its first batch of Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine from the Serum Institute. And it was an order for just 11 million doses – in a country of nearly 1.4 billion people. The government also pledged to order another 45 million from Serum and a smaller number of doses of another vaccine from another Indian company, Bharat Biotech.

At the time, coronavirus cases had hit record lows in India. So there wasn't much urgency. Opinion polls revealed some vaccine hesitancy among the public. And the government was still negotiating with Serum for better prices before ordering more.

The Indian government eventually did up its order and even donated tens of millions of doses as a gesture of goodwill to neighboring countries – and, analysts say, to compete with Russia and China, which have been selling and donating their own vaccines around the world.

Then a second wave of COVID-19 exploded across India – and the country desperately needed those vaccines it had given away.

'A Series Of Missteps' Amid Increased Demand

Throughout April and May, Indians died of COVID-19 in record numbers. Many couldn't get ambulances. Hospitals ran out of oxygen. At its peak, India was confirming more than 400,000 coronavirus cases a day and more than 4,500 daily deaths. But the real numbers may be many multiples higher because coronavirus testing collapsed too.

Amid rising demand for vaccines at home, the Indian government quietly cut back on vaccine exports in April, redirecting those doses to the domestic population.

"It's unofficial of course, but India is going to be using all the vaccine manufactured in the country," says Malini Aisola, one of the leaders of the All India Drug Action Network (AIDAN), a health-care watchdog. "There is nothing left for export."

In late May, Serum acknowledged that it would be unable to supply coronavirus vaccines to COVAX, the WHO's program to distribute vaccines to lower-income countries, until the end of this year. Serum was supposed to be the program's biggest supplier. In addition to COVAX, dozens of countries had placed orders with Serum and in some cases even paid for vaccines they never received.

Meanwhile in India, even with all of Serum's output redirected domestically, there still wasn't enough. Hundreds of vaccine centers across the country were forced to close temporarily in April and May for lack of supplies. Hundreds of thousands of Indians who'd managed to get a first dose couldn't get a second one.

On May 1, shortages were further exacerbated when the Indian government opened up vaccinations to all adults age 18 and up – without enough supply. At the time, health and frontline workers still hadn't all been inoculated. Huge lines formed at vaccine centers across the country, and thousands of them ran out of shots and had to shut again.

In mid-May, the government also lengthened the interval between doses of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, requiring people to wait 12 to 16 weeks for a second dose. The government denies it was rationing vaccines, and defended the interval decision as based on scientific data. But members of the government's own scientific advisory board told Reuters they did not back the decision.

"Unfortunately I think there has been a series of missteps. The current situation was not entirely unforeseeable," Aisola says. "There was always going to be a large amount of vaccine required to immunize a huge population, and the government really should have made efforts not just in terms of purchasing but also efforts early on to utilize unused capacity."

She says unlike the United States, which invoked the Defense Production Act to bolster vaccine production, India failed to use government authority to ramp up manufacturing and also exported or gave away early supplies.

It also allocated 25% of its vaccine supply to private clinics, where prices were out of reach for a majority of Indians.

"What Happens When You Put All Your Eggs In One Basket"

Serum had pledged to ramp up its production, telling NPR in early March that it would soon be churning out 100 million doses of Oxford-AstraZeneca per month.

That never happened. The company has been producing 60 to 70 million doses per month instead. It has cited price caps by the Indian government, lack of raw material exports from the U.S. – and a fire that damaged part of its facility.

"It's a demonstration of what happens when you put all your eggs in one basket," says Milan Vaishnav, director of the South Asia program at the Carnegie Endowment in Washington D.C. "Frankly, the Serum Institute's story — what they're telling to the U.S. government, what they're telling to the government of India, what they're saying publicly — those stories don't match up."

In late April, amid rising public anger over shortages of vaccines, Poonawalla left India for the United Kingdom. He told a British newspaper he faced "threats and aggression" from VIPs in India who couldn't get their shots.

A spokesperson for Poonawalla told NPR he returned to India in late June. While NPR interviewed him in summer 2020, he has refused several requests for a follow-up interview.

Signing Up For A Vaccine: 'Definitely A Challenge'

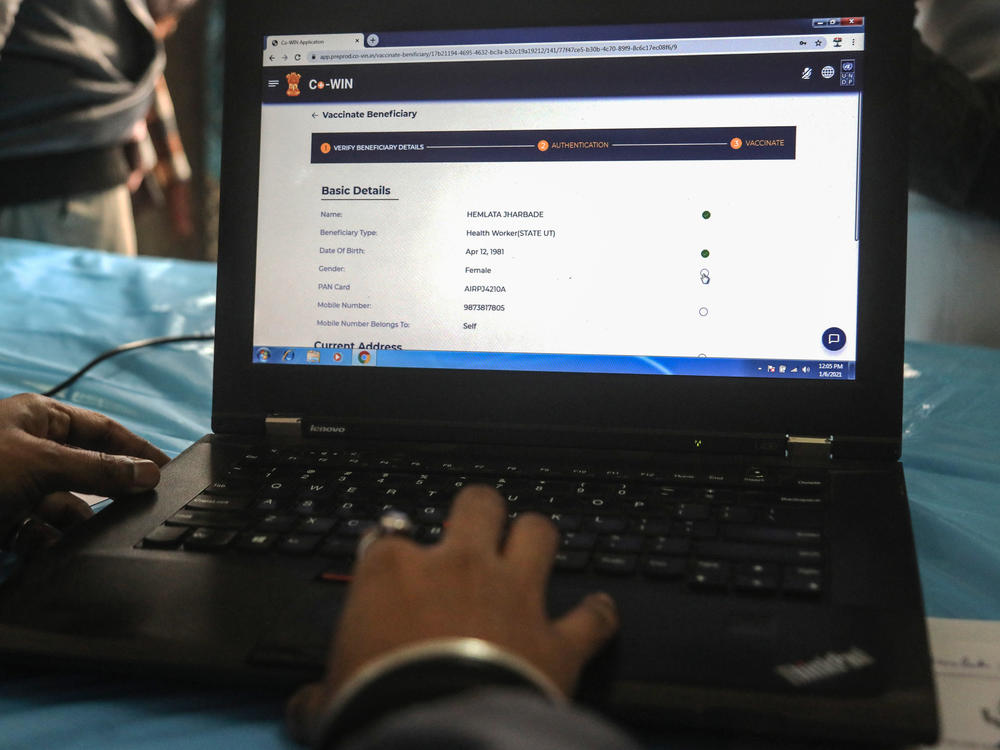

Amid high demand and low supply, it's been difficult to book vaccination appointments in India. Initially, all appointments had to be booked on a government website or app called CoWIN. But they're notoriously buggy. When NPR visited a vaccination center north of Mumbai back in late January, even hospital administrators were having trouble using CoWIN, amid power cuts. Social media has been full of comments by users exasperated by glitches on the app and website.

So Berty Thomas took matters into his own hands. He's a computer programmer who, in the wake of these glitches, built two apps – one for the under-45 age group, and another for those over 45. (On CoWIN, vaccine eligibility is different for those two groups.) Thomas' apps essentially monitor CoWIN and alert users when slots for appointments open up. His service sends out a text message instructing users when to get online and book. More than 3.5 million people in India have used Thomas' tools – and a few others have since emerged too.

"On one hand, I like that the government is doing a technology-driven vaccine rollout. There needs to be a central database where they know who is getting vaccinated," Thomas says. "But at the same time, there are places where people do not have access to internet. So this is definitely a challenge."

Hundreds of millions of Indians lack smartphones or regular access to the internet. Several tens of millions of Indians also are unable to read. At first, the CoWIN app was only in English – spoken by a minority of Indians — but it has since expanded to 12 languages.

Earlier this month, all government vaccination centers began accepting walk-ins for registration.

"I tried and tried but for months I wasn't able to book a shot online," one man told local TV, relieved that he could finally register in person at a clinic in the capital New Delhi.

Modi Hits Back At Criticism

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has come under widespread criticism for problems with the country's vaccine rollout. He was also attacked for holding election rallies – with scant social distancing – as coronavirus cases were rising in April. His approval ratings have dipped.

After several weeks of silence, Modi gave a televised address to the nation on June 7 in which he hit back at some of the criticism.

"We should remember that our rate of vaccination is faster than many more-developed countries, and our tech platform CoWIN is also being appreciated," Modi said.

He's right in terms of real numbers: India has administered more than 330 million vaccine doses. But most of those are first doses. The vaccines used in India require two. So India has a long way to go before a majority of its nearly 1.4 billion people have some protection.

Modi also announced a major policy reversal: Starting on June 21, everyone in India age 18 and up became eligible for free COVID-19 shots. Previously, Modi's central government agreed to vaccinate only those aged 45 and up at no cost — and left it to individual states to obtain and provide vaccines for younger people, often for a fee.

Aisola, the public health advocate, says she approves of the reversal. It's something the Indian government should have done from the beginning rather than leaving it to individual states to try to procure vaccines on the global market, she says.

"Centralized bulk procurement is really the most efficient way to keep the price low, and also to optimize public resources," Aisola says.

Finally, A Record Vaccination Day

On June 21, India administered some 8.6 million shots – a daily record for any country except China. Officials said it was possible because fresh supplies that the government had ordered during April and May are now finally coming online.

"This is a new chapter in the war on corona," India's home minister Amit Shah told supporters that day in the western state of Gujarat.

But an analysis of state data by local media shows states ruled by Modi's Bharatiya Janata Party, or BJP, may have withheld vaccinations in the preceding days in order to achieve that one-day record.

India's health minister claims all Indian adults will be able to get fully vaccinated by the end of this year. But even with increased supply, that target may be too ambitious, experts say.

"If we are able to give two doses to all the vulnerable, and if we can give one dose to the rest of the population, then we are in real good shape," says Dr. Giridhara Babu, a Bengaluru-based member of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), which is basically India's equivalent of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Babu says he hopes that by late July, India might be able to vaccinate up to 10 million people a day.

Vaccinating quickly, 'preparing for a third wave.'

Dr. Daksha Shah isn't taking any chances. She's a municipal health official in Mumbai — where, despite declining infections, she's setting up new field hospitals.

"We're slowly opening up the economy, plus doing the vaccination drives — but at the same time, we are keeping a watch on daily positivity [rates] and on bed occupancy in the hospitals," Shah says. "So we are preparing for the third wave also in case it happens."

India's second COVID-19 wave was spread in part by attendees at a huge religious gathering in April on the banks of the Ganges River. Again this month, thousands of faithful gathered there to take a ritual dip in the river they consider most holy – despite local rules banning large gatherings.

"We have taken a bit of risk in coming here," one devotee told local TV. "But we have taken all the safety precautions, like masks and hand sanitizers."

Meanwhile, whenever you make a phone call in India these days, you hear a similar message: "Wear your mask properly, wash your hands frequently, and yes, do not forget to take your vaccine on your turn."

It's a COVID safety message from the government that plays before the ringtone for all phone calls.

Hundreds of millions of Indians would like to heed that call – including Rekha Gala, the photocopy shop owner in northern Mumbai.

But she's still waiting her turn for a second dose of COVID-19 vaccine. And she only managed to book an appointment for her first dose, with help from a local politician. She reached out to him after having trouble booking an appointment on CoWIN.

"The government is trying its best, but sometimes you have to go around and use your connections. It's difficult. We have to take care," Gala says.

Right after she got her first dose, the government changed the rules, and she has to wait 84 days for her second dose. She says she just hopes another wave of COVID-19 doesn't hit Mumbai before that.

NPR producer Sushmita Pathak contributed to this story from Hyderabad, India.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.