Section Branding

Header Content

'He Left Me All Alone In The World': India's COVID Widows Struggle To Survive

Primary Content

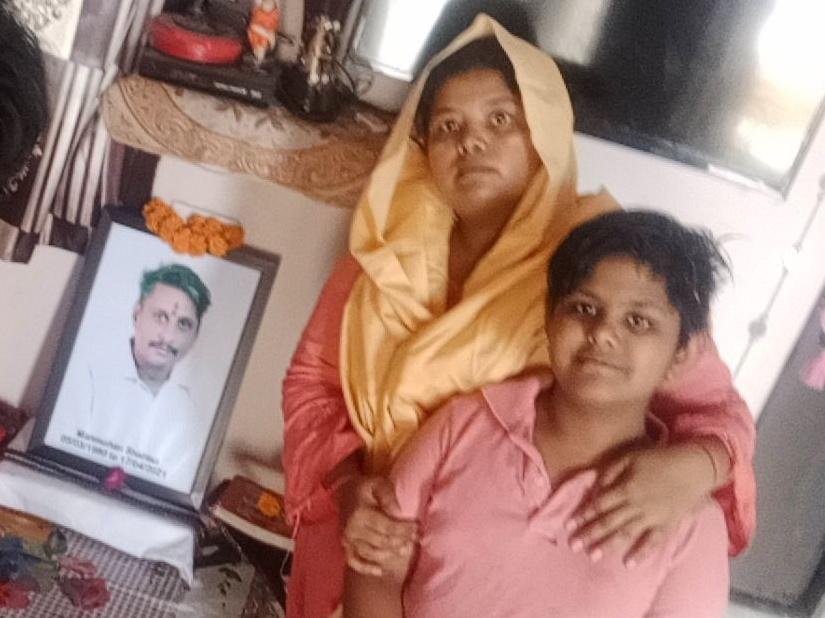

When Pooja Sharma, 35, lost her husband, Manmohan, to COVID-19 during India's deadly second wave, she was devastated.

"After a few days of battling COVID-19, my husband realized he wasn't going to make it," Sharma says. "He asked me to take care of our daughters, then he left me all alone in the world."

Manmohan, who died April 17, was the main provider of their family. He had a job ushering people into clothing shops on commission. Without him, Sharma, who lives in Delhi, wasn't sure how she and their two daughters, 12 and 14, were going to live. She didn't have a job and couldn't read. And she was an orphan so she didn't have parents who could help her.

The Indian media are calling women such as Sharma "COVID widows." These are women who have lost a spouse — often the sole breadwinner of the family — during the pandemic. These widows find themselves saddled with additional financial burdens such as hospital bills, while they grieve the loss of their partner. The government and nonprofit groups are now trying to support these women, especially those from low-income backgrounds, but researchers say it's not enough.

India has had more than 30 million COVID-19 cases and 411,000 deaths. More than 200,000 of those deaths took place during the second wave alone, which began in April and peaked in May.

It's hard to measure how many women have been widowed during this second wave, says Rupsa Mallik, director of programs and innovations at CREA, or Creating Resources for Empowerment in Action, one of the largest women's rights organizations in India. She works with women's nonprofits across South Asia and has been following India's COVID-19 widow situation. "There is no data on the number of COVID widows in this country," she says.

The national government does not provide gender-specific data on COVID-19 deaths. But some parts of India, including Bangalore and Pune, have data that shows the mortality rate during India's second wave in their regions has had a greater toll on men – who could be husbands, fathers and breadwinners — than women.

Knowing how many COVID-19 widows there are in India is crucial for the groups that want to help them, Mallik says. "How does one target a policy toward a section of society if you don't have data?"

Cash aid to the rescue?

Despite the lack of information, national and local governments are setting up programs to help these women.

On May 30, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that his administration would implement measures to protect families who had lost their primary earning member, regardless of gender, to COVID-19. That includes a pension equivalent to 90% of the deceased person's average daily wages as well as insurance benefits. Eligible citizens can apply now for payments.

Several state governments in India are also pitching in. The municipal organization of the city of Navi Mumbai, the Navi Mumbai Municipal Corp., announced in June that COVID-19 widows would receive a one-time compensation of about $2,020, plus about $1,346 for any equipment that can be used for self-employment, such as a sewing machine to start a tailoring business. And the state of Assam announced in June that it would give one-time financial assistance of about $3,357 to COVID-19 widows. These are modest sums — in India, a family living below the poverty line usually has an annual income of about $2,416.

Mallik says the cash can be helpful for very poor families who have lost their breadwinner — but there are several concerns. "For a really disadvantaged family with low literacy levels, it is highly likely that male members of the family might try to take control of the money. In patriarchal households, there will definitely be some appropriation of money."

To qualify for government support, widows must show a marriage certificate and a death certificate stating that the cause of death was COVID-19. These requirements create another roadblock, Mallik says. "Even when deaths are registered, they might not be registered as COVID deaths" due to factors such as poor record-keeping. "So disadvantaged families are not able to access the financial assistance."

Job training to survive

The widows – especially from the poorest backgrounds — need more than just cash, says Parmod Kumar, director of the Institute for Social and Economic Change, a think tank based in Hyderabad that helps women in rural areas through agricultural development.

Nonprofit organizations are now providing a variety of resources for the COVID-19 widows, Mallik says. "They are filling in the gaps in areas where the government is lacking." These include grief counseling and mental health services.

But there's also a pressing need for practical support, which charities are also providing. "The COVID widows need to be independent," Kumar says. "They need to start employment if they want to support their families. Skilling these widows [through job training] will help them in the long run."

Sharma now works with a nonprofit group called Pins and Needles, which helps hundreds of women in Delhi use their domestic skills such as sewing and knitting to make handicrafts such as aprons, masks, toys and earrings. These items are showcased on the group's Instagram and Facebook account; customers, mostly in India, can order directly from a website.

"All the proceeds from the items go to the women," says Simran Kaur, founder of Pins and Needles.

Over the past few months, the group has been reaching out to dozens of COVID-19 widows. For women such as Sharma, the program was a lifeline. "After my husband died, it seemed like my world was over," she says. "Who was going to give a job to a poor, uneducated woman like me? I thought of taking my life because I couldn't think of a way to take care of my daughters."

Sharma earns about $60 a month selling her handicrafts. While she's grateful for the money, she wishes she could make more. When her husband was alive, he was bringing in up to $240 a month for their family. That put them just under India's poverty line but was enough to them afloat, she says.

Still, Sharma says the job makes her feel a little more confident about living on her own. But nothing can replace her late husband, Manmohan, she says. He was the love of her life.

His family didn't approve of Sharma because she was an orphan, but he married her anyway. That's how much he wanted to be with her.

Wiping away tears, she says, "I miss my husband."

Agnee Ghosh is a freelance journalist based in Kolkata, India, who has written for South China Morning Post, The Globe and Mail and Atmos. Follow her on Twitter @agnee__.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.