Section Branding

Header Content

A Bright Spot Amid Haiti's Woes: Its 1st Mass Rollout Of COVID Vaccines

Primary Content

In the wake of one of the most devastating moments in Haiti's arduous history, there has been a bright spot.

One week after Haiti's president was assassinated, the country's first shipment of COVID-19 vaccines finally arrived.

President Jovenel Moïse was shot a dozen times in his private residence on July 7. Despite the political chaos, social disruption and a national "state of siege" that followed the killing, Haiti has now launched a mass COVID-19 immunization drive for health care workers and people over age 65. Haiti is one of the last countries in the world to make the vaccine available.

The big question now is whether Haiti can overcome the political instability and high levels of distrust among the general public to actually get people vaccinated.

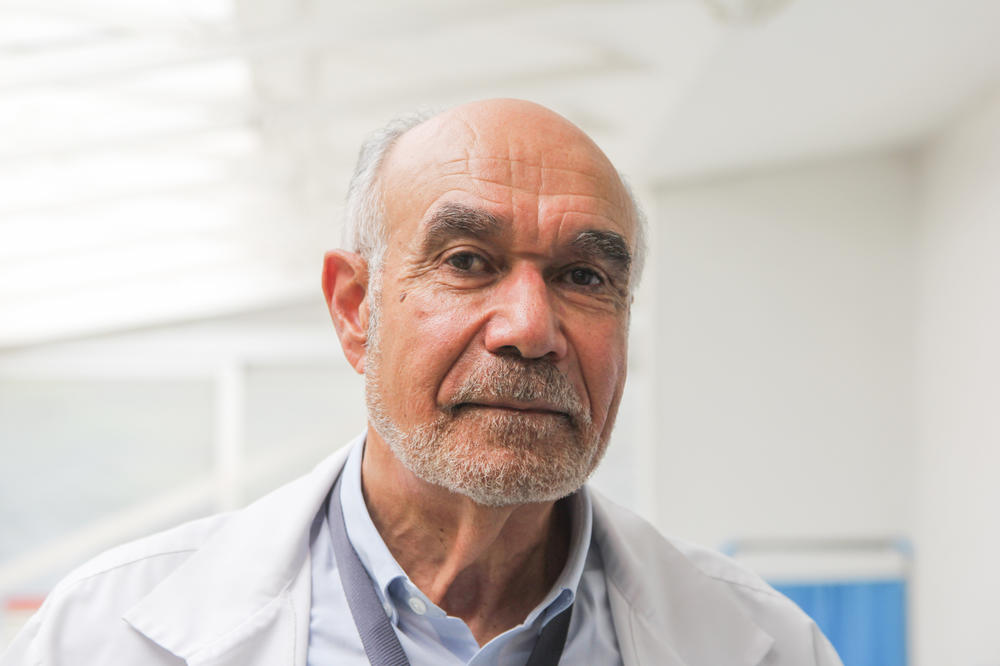

But some health officials are optimistic. "It's a huge boost for us," says Dr. Jean William Pape of the recently arrived vaccines. He is a veteran physician who has been on the front lines of Haiti's HIV/AIDS crisis and co-leads the country's efforts against COVID-19.

Earlier this year, Haiti shrugged off two offers of doses AstraZeneca — first from India and then from COVAX, the global vaccine sharing program. Case numbers at the time were low in Haiti, and COVID-19 wasn't high on the list of concerns for Haitian officials or even many residents.

But after cases started to surge in May, health officials in Port-au-Prince decided to move forward with efforts to launch a mass immunization program. And in mid-July, the U.S. sent half a million doses of the Moderna vaccine through COVAX to the Caribbean nation.

"It's an excellent vaccine," says Pape. "We are very happy to have it."

Bigger problems to worry about

The medical facility that Pape runs, Gheskio Hospital, is surrounded by the social ills that plague Haiti.

The hospital sees roughly 2,000 patients a day, from kids with fevers to HIV patients, but it backs up against Village-De-Dieu, or "City of God" — a lawless neighborhood between Port-au-Prince and the bay. Over the past two years, Haiti has been hit with a significant surge in gang violence. Criminal organizations have taken over entire neighborhoods of Port-au-Prince. After driving out the police, gang members now loot, extort, kidnap and, at times, even kill with impunity.

The area has become so dangerous that my driver didn't want to go there — and the hospital no longer opens its gates on the side that faces Village-De-Dieu. Across the street from the hospital, it looks like a war zone. As Pape walks through the compound, I ask him if all those bullet pockmarks are new.

"Yes, that's correct," he says, as if I had asked about the weather. "It [shooting] happens all the time." Without skipping a beat, he points out the courtyard of his tuberculosis clinic.

Moïse's assassination sent a chilling message about the breakdown of the rule of law in the country.

"It's a very sad time for the country. Very, very sad," Pape says, shaking his head. "If the No. 1 person in the country can be killed so easily, everybody can be killed."

In addition to shocking levels of violence, many Haitians are struggling to make a living. Poverty has risen in Haiti during the pandemic, according to the World Bank, and now roughly 60% of the population lives on less than $2 a day.

The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) warned in a memo in July that the volume of issues on Haiti's plate could leave it vulnerable to a devastating COVID-19 outbreak. The population is taking few precautions against the virus. Hardly anyone is vaccinated. And resistance to the vaccine is high. According to a survey conducted in June by UNICEF and the University of Haiti, only 22% of adults were open to getting it. The hesitancy is driven in part by people not viewing COVID-19 as a threat and in part by concerns amplified by social media about side effects.

The PAHO memo adds, "The security situation could deteriorate even further and hurricane season has started."

A changing pattern of COVID cases

In the early days of the pandemic, Pape and his staff observed more sporadic COVID-19 infections. Now, presumably because of the new variants, Pape is seeing more clusters of cases.

"Now everybody — the family members, the servants" — are getting infected, he says. "Once one person gets infected, the transmission goes to the entire household. So that's different."

But up until now, the number of reported infections and deaths has not been overwhelming. The reported rate of infections per capita is 30 times higher in neighboring Dominican Republic than in Haiti, which has 1,745 cases per one million people.

And deaths attributed to COVID-19 in Haiti remain low. Officially, just over 500 Haitians have died of COVID-19 so far in the pandemic — half the number of fatalities that occurred in the first month of Haiti's devastating cholera outbreak in 2010.

By all accounts, these numbers are underestimates; testing is even far less frequent in Haiti.

Pape says random antibody screenings of patients at the Gheskio clinic show that many Haitians have already been exposed to COVID-19.

"The majority of my patients — the poor people — they are getting infected," he says. "Sometimes they have symptoms but not enough to require hospitalization or even ventilation care."

Many don't seek medical care for COVID-19 at all — because they can't afford to go to a clinic or because their symptoms are mild or nonexistent.

Pape says new variants of the virus, especially the alpha variant that was first identified in the U.K., have led to more severe cases in Haiti. So far, the delta variant hasn't been documented, but the country doesn't have the capacity to test for it.

For the first time, his staff has had to medically evacuate COVID-19 patients out of Haiti to get more advanced treatment. The country doesn't have the medical facilities to handle them, so some patients are sent to Cuba, the Dominican Republic or Miami.

Making headway on vaccinations

"Yes, Haiti is having a lot of challenges lately," says Ciro Ugarte, the head of health emergencies at PAHO. Despite those challenges, he says the shipment of Moderna doses is being distributed to clinics in all 10 departments, or states, in the country.

The majority of the first shots were given in parts of the North and West departments, which include Haiti's most populous cities, Port-au-Prince and Cap-Haitien. So far, more than 3,000 doses of the Moderna vaccine have been administered.

Ugarte notes that measures are being put in place to have the vaccine available across the country soon, including at private clinics. "They're planning for 10 [vaccination] sites in the West department," Ugarte says, "and three sites per department in the others."

Pape is confident that resistance to the vaccine will wane as it becomes more widely available.

It may even help bring the traumatized country together, he says. He hopes the gang members from across the street— the "bandits," as he calls them — will also come in to get immunized.

"If my worst enemy comes to me, my job is to take care of him," Pape says. "Our job is to vaccinate people and make sure they don't die of COVID."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.