Section Branding

Header Content

A Onetime Nomad Reflects On The Beauty And Harshness Of Life In The Somali Desert

Primary Content

Sometimes when Shugri Said Salh is running errands in Sonoma, Calif., where she currently lives, she says she has "visions" of her former life as a young nomad in Somalia. For example, one day, while eating sushi in front of Whole Foods, she spotted a customer carrying an African-style basket and a water jug — and suddenly she was transported.

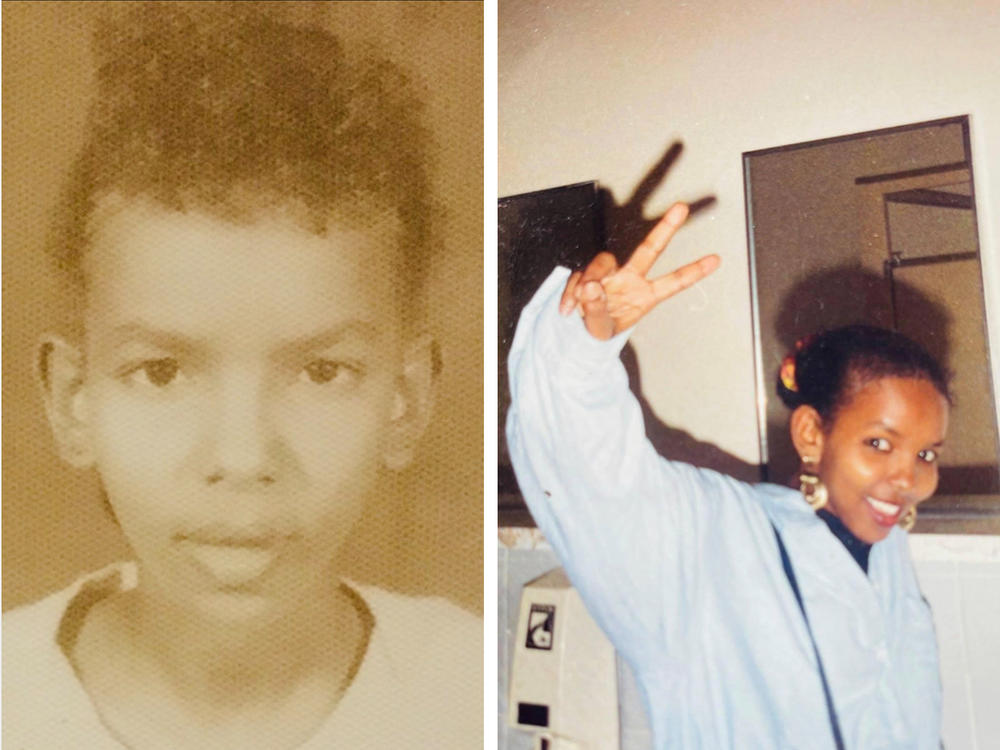

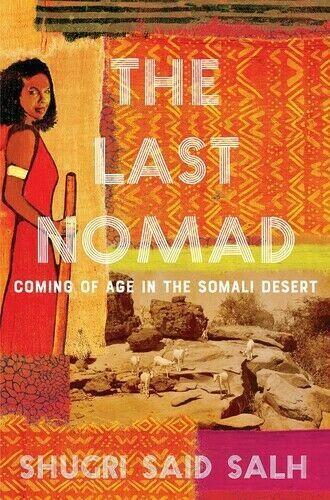

"Instantly, I was standing in front of my desert hut, eyes fixed on the scorching terrain," she writes in her memoir, The Last Nomad: Coming of Age in the Somali Desert, recalling the incident. The book, published in August, chronicles Salh's journey from her childhood in Somalia — where she and her family lived as goat- and camel-herders — to her life as a nurse and mom of three in the U.S.

Between those phases, Salh, 47, faced challenge after challenge. She underwent female genital mutilation, a rite of passage for girls in her tribe. She fled with her family to the border of Kenya in 1991 following the outbreak of war in her country. Then in 1992, she and her family emigrated to Canada, where they had to adapt to a new way of life, eventually resettling in the U.S. in 1999.

Yet through these hardships, Salh found a way to survive and even thrive. We spoke to her about bridging two very different worlds and passing on her nomadic knowledge to her children. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Your parents sent you at the age of 6 to live with your grandmother in the Somalian desert. They lived in the city, but they wanted you to learn the ways of your nomadic heritage. Describe who nomads are in Somalia.

People who live in the desert who have livestock, such as camels, goats and cows, and who are one with the environment. We were constantly in pursuit of grazing land or water. Our life depends on the rain cycle. No rain means no grazing land and no food for our animals — and ultimately that means no food for us.

What did you love about being a nomad?

Sitting by the fire, nibbling on meat from a goat that was just slaughtered. Listening to stories, poems and riddles passed down from generation to generation. I loved waking up to the sounds of goats bleating and camels bellowing. There was also the time I tried to ride an ostrich. That didn't work out so well!

Your grandmother arranged for you at age 8 to undergo female genital mutilation. In your culture, it is seen as a way to preserve virginity before marriage. You wrote in your book that you did not want to "show fear and disrespect" to her at the time – so bravely went through with the procedure. What was that like? How do you feel about it now?

It was really hard. But I wanted to give readers insight into why a culture would do this. If I did not go through FGM, I would have been ostracized. Kids would have picked on me. At my school, children would accuse each other of not being circumcised. And then you had to go into a corner and flash each other to prove you were. We were superior to uncircumcised girls. No one would have married me.

Now I feel it's barbaric. To this day, I still deal with the ramifications from the process, although I did get the procedure undone [in a process called deinfibulation, which opens up the vagina but does not replace any removed tissue or undo any damage caused]. This butchering of young girls should not continue. I broke the shackles of this legacy. My daughters were not circumcised, and nor will they circumcise their children.

In 1991, when you were a teenager, you and your family fled to a village on the border of Kenya as a result of Somalia's civil war. There, you lived among other refugees in overcrowded conditions, with little food or water, under the constant threat of sexual assault from men in the village. What was life like?

We arrived at the border of Kenya with about 250 others, all from different areas of Somalia who had fled the same fighting. That was a really desperate and hard time. Children were dying from dysentery, people were getting sick [due to lack of food and health care in the village]. The hardest part was not knowing if I would be OK, if safety would come — and knowing that you could be killed or raped [by male refugees in the village or the guards who patrolled the border] at any time. There was a lot of uncertainty.

Eventually, in 1992, you, your parents and your siblings were able to escape to Canada. How did that happen?

My sister Saada was already living as a refugee in Canada, and she helped us with the papers. We were some of the few lucky people who managed to escape. We arrived in Ottawa in the thick of winter. The mountains were completely white. "What is that?" I asked my sister. "Baraf," Saada replied. Baraf is the Somali word for ice. We don't have a word for snow. I had to remind myself that I was living the dream of all those desperate refugees stuck in Kenya. I was going to the land of opportunity.

What was life like in Canada after you first arrived?

I started English lessons, which I quickly learned. I was living with my older sister, but I ended up having to escape her house, because she was treating me as a maid. Then I took classes — which were like a bridge between high school and the first year of university — and that's where I met my husband, at an advanced biology class. Eventually, we married and moved to the U.S. [for his job as] a software engineer, and in 1999 we moved to California.

Do you tell your kids the stories from your childhood? What do they take from them?

I have told my children my stories, and it inspires them to overcome challenges. When my son was 10, he was worried about being small for his age. So I told him about how his grandfather was a warrior. He was a small guy, too, but he was really strong. Today my son is a teenager — and he's not as small as we thought he would be!

Your life now as a nurse and mom living in Sonoma is a far cry from your life as a nomad. When do you feel closest to your roots?

When we go camping with my family or my friends, we gather around and tell each other stories [like my family used to do in the desert].

What has your upbringing taught you about life?

Wherever I am, I can always make friends, and it's because I have had to move for most of my life. I am also very resilient, and that is because of my childhood as a nomad. We were always against harsh elements. We lived at the mercy of the rain, through drought, among wild animals — yet we survived, thanks to the knowledge that has been passed down for generations. That adaptability from my ancestors is woven into me, and I too can strive no matter what.

Lucy Sherriff is a multimedia journalist based in LA. She covers climate and environmental justice issues.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.