Section Branding

Header Content

Child grooms are often overlooked in the fight to stop child marriage

Primary Content

The teenager dreamed of becoming a doctor. But that dream was derailed by child marriage. It's a familiar story – but in this case the details may surprise you.

The 15-year-old wasn't a child bride. He was a child groom.

Child marriage – defined by the United Nations as marriage under age 18 and considered a violation of human rights – disproportionally impacts girls. An estimated 650 million girls and women were married as children.

But there are also child grooms. In its first ever in-depth analysis of child grooms, published in 2019, UNICEF estimates 115 million boys and men around the world were married as children.

They too suffer because of young marriage. "Child grooms are forced to take on adult responsibilities for which they may not be ready," says UNICEF executive director Henrietta Fore. "Early marriage brings early fatherhood and with it added pressure to provide for a family, cutting short education and job opportunities."

In addition to perpetuating the cycle of poverty, child marriage has a powerful psychological impact. Based on what he's seen, Pashupati Mahat, technical director and senior clinical psychologist for the Center for Mental Health and Counselling – Nepal, says that boys forced into child marriage suffer higher rates of depression, loneliness and even suicide than do child brides.

"Young men force themselves to be adults, but they don't have the psychological resources to cope with all the demands," says Mahat. "There is more isolation, alienation and a lot of psychological pain within themselves. They are not skilled enough to provide the good affectionate, emotional support [and] use a punitive parenting style. They don't want to face the difficult emotions of the child because they never got the opportunity to deal with their own emotional difficulties when they were quite young."

A would-be doctor derailed

The teenager who wanted to be a doctor, Chakraman Balami, lives in Nepal, which ranks among the countries with the highest rates of marriages involving a child groom. That rate is estimated by UNICEF at 1 in 10. The highest rates are in Central African Republic (28%) and Nicaragua (19%).

The practice of child marriage persists in Nepal despite the fact that it's been illegal since 1963. Current law sets the minimum age of marriage at 20 for both men and women. However, it's rarely enforced.

Now an adult, Balami has become an activist against child marriage. And in 2022, his mission is still a challenge.

The cultural forces that lead to child marriage have not diminished. In Nepal as in many other countries, the practice is part of longstanding tradition. And families may see little advantage to keeping their youth in a classroom when they're so desperately needed elsewhere.

"In the village, the parents who want their kids to marry, they see only immediate benefits," explained Chakraman. "They see free labor, they see one more person able to take care of the household chores, food, field, agriculture." At the same time, they do not consider the harmful repercussions of child marriage.

The pandemic has made matters worse. UNICEF predicts that an additional 10 million girls are at risk of marriage over the next decade as a result of economic repercussions caused by COVID-19.

In Nepal, for example, where on-and-off lockdowns have decimated the ability of farmers to earn a living, parents are eager to marry off their children to have one less mouth to feed. Both girls and boys are affected .

Initial data from the pandemic period shows that boys as well as now facing a greater risk of marriage: In Balami's village of Kagati, 9 underage girls were married in 2020, compared to 7 the year before, and three teenage boys were wed, while there were no child grooms in 2019.

From top student to unwilling groom

Before he became a groom at age 15, Chakraman was a top student at his secondary school near Kathmandu with no interest in early marriage.

But when he was around 13, his father became critically ill. His dying wish? To see his son get married.

"I felt very bad," says Chakraman. "But I respected my parents. I listened to them. I wanted to fulfill their wishes." So in 1993, he reluctantly agreed to marry at age 15, shortly before his father's death. "People have a mindset, a belief system that if you arrange your son's marriage or if you see your son getting married, then your life will be fulfilled."

Barely an adult, Chakraman became a father at 18 — but the baby died just five days later, leaving the young couple heartbroken. The couple subsequently had two children. The funds he would have invested in his education went toward providing for the youngsters.

So his dream of medical school was not to be. "When somebody's dreams are taken away, you get emotionally hurt, you get affected," says Chakraman. "I have a lot of anger when I think of the life I never got to make for myself."

But he did persevere to complete his education over a span of 20 years. He recently earned a master's degree in Education Planning Management. These days, Chakraman is the vice principal of Shree Bhawani Primary and Secondary Schools.

While his own dreams of medical school have faded, he hasn't given up on those of his students. He encourages them to finish their studies before considering marriage. It's been a decades-long fight.

But the group's best arguments have a hard time overcoming long-held traditions, economic challenges and family pressures. Child marriage has continued into the next generation. Even Chakraman's own son and niece would ultimately marry before they reached adulthood.

Even in communities more amenable to delaying marriage, when adolescents begin romantic relationships, parents may push for child marriage as they worry about premarital pregnancy bringing shame to families.

Why it's so hard to stop child marriage in Nepal

Chakraman understands all too well how hard it is to stop this practice.

Not long after his own wedding, he and more than 40 of his male teenage friends – all of whom were married or engaged as children – formed the youth organization Mahalaxmi Janajagriti Yuba Pariwar, which translates to Mahalaxmi Awareness Youth Club. The volunteer group was named after the temple where these marriages take place and was aimed at preventing their neighbors and relatives from facing the same fate. "Whenever we heard about a child marriage, we would try to convince parents and family members to stop it. If they didn't listen, we went to the bride and groom," he explained. "If that still didn't work, [we would] smash all pots of alcohol they make at home for the wedding feast."

The plan backfired. Villagers viewed the activists as disobedient, blaming their rebellious behaviors on their education and consequent exposure to ideas outside the social norm. The backlash even led some families to briefly question sending their children to school at all. The youth group eventually turned to less extreme methods, focusing on peer support and training to achieve its goals.

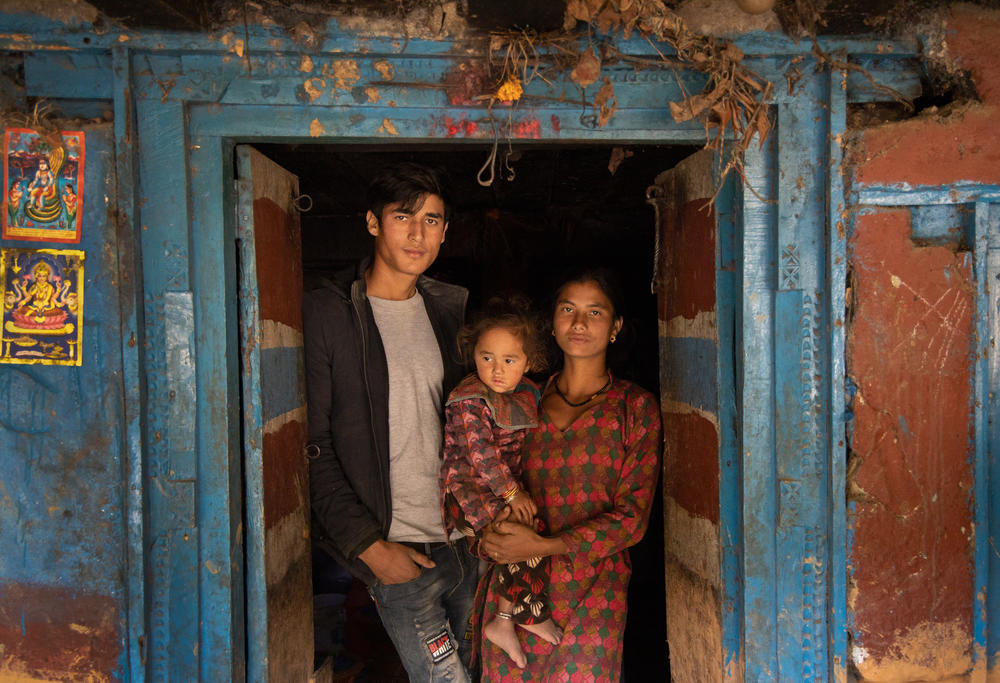

Chakraman has also been unable to forestall child marriage in his own family. Along with several other teen couples, his niece Sumeena was married at age 13 on the festival of Shree Panchami, considered one of the most auspicious occasions for weddings in the Hindu religion. Chakraman reluctantly performed some of the wedding rites. Her groom, Prakash Balami, was 15. Almost immediately, Sumeena became pregnant.

"We suffered a lot," recalls Prakash, now 30. "She became dizzy, she was sick all the time.

"I was very young then – I was a child," he says. "I didn't know much about weddings or marriage."

Sumeena's underdeveloped pelvic bones made for a difficult and painful delivery that quickly became life-threatening to both her and the unborn child. She was rushed to the hospital for a cesarean section.

While Sumeena and their son, Mukesh, survived, the pregnancy abruptly ended her education. The young family's financial demands drove Prakash out of school shortly thereafter.

"After my son was born, my childhood was gone," he says. "I was very much interested in social work before I got married. I thought if someone had a problem, I could go help. I really like helping people, but that's all gone."

When his son reached school age, Prakash took a job in construction for two years in the sweltering, year-round heat of Qatar, planning to earn money to send home to his young family. But he says his earnings were withheld to ostensibly pay off the recruiter fees. He returned home empty-handed, unable to afford even a school uniform for his son.

"I thought I would earn a lot for my family, for my children," says Prakash. "That was my dream. But nothing turned out the way I thought it would."

Satellite TV and the internet add a complication

In an ironic twist, the modern age, with increased access to satellite television and internet on smart phones, has reinforced the practice of child marriage. In previously sheltered Nepali villages, South Indian movies blast melodramatic love stories nightly into homes, with young eyes watching. The result is a surge in teen romance – and in parental fear that their daughters will defame the family by having premarital relations.

"We fell in love in grade nine," explains Chakraman's son, Nirazan Balami. "But we were kind of forced to marry because her father came to know we were in a relationship. I was 17."

Smitten, the teenage Nirazan says the girl's father overheard him saying "love-related things a boyfriend says to a girlfriend." The father insisted the couple immediately become husband and wife.

In shock and overcome with stress, Nirazan tried to calm his nerves with alcohol. Then, he called his mother saying he wanted to get married.

"My mother told my father because I couldn't bear to tell him. When he came to know, he shouted at me, 'No, no, no! Not now! This is not the right decision!' "

Chakraman arrived in Kathmandu the following morning to take Sanjeeta back to her father's house. A few days later, Nirazan returned to the village to find his parents still distraught and angry. Sanjeeta had been calling him daily in response to her father's relentless pressure to marry Nirazan.

In an effort to placate Sanjeeta's father, Nirazan finally convinced his parents to let them get engaged.

His mother acquiesced and immediately began making arrangements for the wedding.

"That's how I got married," says Nirazan.

For a while, Nirazan was able to return to veterinary school. But the newlywed couple soon married. In 2017, they had a child, and, like his father, Nirizan's education came to a halt.

"I felt pressure to earn money because I had a family. I felt very depressed. I thought, I don't know, why should I live?"

Before long, Nirazan got a job as an excavator driver. He's held the job for several years – and still can't help but wonder what his life could have been like had he been allowed to continue his studies.

Economics could be a key to convincing parents not to marry off their children. High-ranked officials in the village, including former members of the youth club, say the pace of change will remain incremental at best until many parents see economic benefits of letting their children continue their education – both girls and boys, the pace of societal change will remain incremental at best.

Will things ever change?

Clearly, child marriage for boys will not end unless it ends for girls, says Anju Malhotra, a fellow at the United Nations University-International Institute for Global Health and a global leader in gender issues.

For this to happen, families have to realize that there's an economic benefit to keeping girls in school – a tough idea to embrace during a pandemic and when climate change is having an impact on harvests, she says.

And while there are clear career paths for sons, she says that families don't have enough awareness that the same should be true for daughters.

She says there also must be programs in villages to sensitize families on the importance of decoupling their reputation from their daughter's intimate decisions – and that those decisions should not be cause for immediate marriage.

Without these changes for girls, the boys will also be unable to break free from pressure for child marriage, says Malhotra.

Had they just postponed the wedding, Nirazan says he feels that his life and his wife's life would be much different today. He wishes he could have communicated that to his wife's parents.

"Now," he says, "we've both sacrificed our dreams."

In a career that's spanned over two decades, Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer Stephanie Sinclair has focused on gender and human rights issues, with special attention to the topic of child marriage. In 2014, she founded the charitable organization Too Young to Wed, whose mission is to empower girls and end child marriage globally.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.