Section Branding

Header Content

A 4-year-old can run errands alone ... and not just on reality TV

Primary Content

Editor's note: This story discusses the practice of giving children the freedom to go out on their own. In some places, parents who allow young children to run errands or go places without adult supervision may violate local laws. Parents interested in this topic should be sure to familiarize themselves with the law and rules in their community.

A few years ago, my husband and I had a bit of a situation on our hands. Our 4-year-old daughter had figured out how to climb onto the roof of our home. After breakfast in the mornings, we would find her perched, like a pigeon, three stories above a busy city sidewalk. (It makes me a bit nauseous to think about it).

The first morning, I tried to coax her down by asking her nicely ("Rosy, please come down. That is dangerous."), nagging a bit ("Rosy, I'm serious. You have to come down. Please. Please") and eventually issuing a flimsy threat ("Ok. If you don't come down, we won't get ice cream on Friday.")

Then the fourth time she went up there, I was a bit fed up and decided to try and fix the root of the problem, instead of just the symptoms. I was in the middle of writing a book about parenting around the world, and I had heard the same advice over and over again: When a kid misbehaves they need more autonomy; they need more responsibility.

In particular, Maria de los Angeles Tun Burgos, a mother in Yucatan, Mexico, put it quite succinctly: "Can Rosy go to the store and run an errand for you," she suggested after I told her about Rosy's escapades.

So, looking up at the little daredevil hovering over the gutters, I decided she was finally ready to do just that. So I said to her: "We're out of milk. Can you run up to the market and buy us some milk?" The market is two blocks away.

"All by myself?" she asked with a twinkle in her eye.

"Yes, all by yourself."

Boy, did that chore change her behavior.

Now a Japanese reality show, streaming on Netflix, is reminding me of that pivotal moment – and the importance of a seemingly trivial task on children's lives — all around the world. It's not so much about raising "free range" kids – the term often used to describe children who are free to play and explore around their homes and neighborhoods on their own — but rather it's about raising smart, capable kids whose parents enable them to practice autonomy without sacrificing safety. Kids who have the skills they need to handle the responsibility.

The show, called Old Enough!, has aired in Japan for more than three decades, but it's new to an American audience. On the show, children ages 2 to 4 are charged with running an errand for their parents. Camera people follow the kids. A narrator comments on their progress.

In the first episode, a toddler takes a 20-minute walk to a grocery store and picks up three items for his mom: flowers, curry and fishcakes.

The little boy couldn't be more than 2 and a half years old. Is that a diaper I see under his shorts? Yet he manages to navigate traffic, find two of the items in the grocery, pay for them and walk out of the store. As if that's not enough, on his way home he remembers that forgot the third item. So he walks back to the store, finds the third item and heads home – waving a yellow flag to help signal motorists to slow down as he crosses a busy street.

It's not clear how much assistance the production crew gives the little boy. And with a laugh track behind the commentary, the show feels a bit silly. Sometimes the commenter even seems to mock the child's actions.

Despite all that, at the end of the episode, I still had this overwhelming sense that the child accomplished something remarkable. Seeing a little tyke – perhaps still in his nappies – handle such a complex task brought this rush of joy through me. And made me think, Wow, kids are so much more capable than we think! And on the flipside: Wow, American society is really holding kids back.

Indeed, Old Enough! shines a fresh light on the American attitude toward giving kids autonomy and responsibility: Our society, as a whole, has somehow forgotten that running errands has massive benefits for kids. As a result, many parents have forgotten how to teach kids to do it.

And it's not like in Old Enough! You don't just hand them some cash and send them on their way. You have to teach them.

Learning to run errands has huge benefits to kids

All around the world, little kids, even as young as ages 3 or 4, run errands for their parents. In fact, if you look across cultures, not running errands is an oddity, anthropologist David Lancy explains in his book Child Helpers.

"Learning to run errands tactfully is one of the first lessons of childhood," anthropologist Margaret Mead wrote in her article "Samoan Children At Work And Play."

For example, kids in many parts of Europe walk to school and make trips to the grocery store alone. "Kids in primary school go shopping at the bakery and the supermarket by themselves, proud of their independence," a reader named Katrin from Germany wrote to the New York Times in 2018.

Same goes for kids in many parts of Mexico. "Of course she can go shopping," Tun Burgos told me about her 4-year-old daughter, Alexa, in 2018. "She can buy some eggs or tomatoes for us. She knows the way and how to stay out of traffic."

Sometimes the "errands" are super, short and quick – and don't require covering any distance. For example, in Tanzania, parents often draft toddlers to move needed objects around home: "Even youngsters who are still walking very unsteadily on their feet are conscripted [asked] by adults to hand knives, beads and food to other nearby adults," anthropologist Alyssa Crittenden wrote in 2016, describing her research with the Hadza community.

But some "errands" can be complex – and long. In a study published in 2009, anthropologists Carolina Izquierdo and Elinor Ochs described a 6-year-old girl in Peru who volunteers to join Izquierdo and another family on a five-day journey down river to fish and gather leaves. The young girl not only travels without her parents, but she's also extremely helpful to the group. "She helped to stack and carry leaves to bring back to the village for roofing. Mornings and late afternoons she ... fished for slippery black crustaceans, cleaned and boiled them in her pot along with manioc [cassava plant] then served them to the group," Izquierdo and Ochs write in the journal Ethos.

As the child becomes more capable, the tasks become more complicated. "Adults match their assignments to the child's level of skill and size and each new assignment ratifies (and motivates) the child's growing competence," Lancy writes in a 2012 paper, called The Chore Curriculum.

No matter the size, these errands help "socialize" children, Lancy writes in his book. The errands teach children how to interact appropriately in society and with adults.

But the errands do something else. Something that's supercritical for kids everywhere: They give kids autonomy.

"Autonomous play has been a really important part of child development throughout human evolutionary history," says behavioral scientist Dorsa Amir at the University of California, Berkeley. "And actually, it was a feature of American society until relatively recently as well."

Autonomy has oodles of benefits for kids of all ages. Studies have linked autonomy to long-term motivation, independence, confidence and better executive function. As a child gets older, autonomy is associated with better performance in school and a decreased risk of drug and alcohol abuse. "Like exercise and sleep, it appears to be good for virtually everything," neuropsychologist William Stixrud and educator Ned Johnson write in their book The Self-Driven Child.

And when children don't have enough autonomy, they can feel powerless over their lives, the pair write. "Many kids feel that way all the time." Over time, that feeling can cause stress and anxiety. In fact, Stixrud and Johnson argue, lack of autonomy is likely a major reason for the high rates of anxiety and depression among American children and teenagers. Autonomy provides the "antidote to this stress," they write.

"The biggest gift parents can give their children is the opportunity to make their own decisions," psychologist Holly Schiffrin wrote in the Journal of Child and Family Studies. "Parents who 'help' their children too much stress themselves out and leave their kids ill-prepared to be adults."

And yet, in America, parents aren't only discouraged from giving kids autonomy, they can get in legal trouble. As NPR has reported, parents in several states have been arrested for leaving kids unattended, for letting them walk to the park on their own or even allowing them to walk to school. This can happen even when the child is clearly not in danger but rather quite capable of handling the autonomy.

"We now live in a country where it is seen as abnormal, or even criminal, to allow children to be away from direct adult supervision, even for a second," the nonfiction author Kim Brooks wrote in a 2018 essay for The New York Times about fear in American parenting.

This situation is especially a problem for parents of color or poor parents, who sometimes need to give capable kids autonomy just so the parents can stay employed. "What counts as 'free-range parenting' and what counts as 'neglect' are in the eye of the beholder — and race and class often figure heavily into such distinctions," Jessica McCrory Calarco, who's a sociology professor at the Indiana University, writes in The Atlantic in 2016. "When children in poor and working-class families stay home or walk to school alone, their parents face considerable risks."

Yet across the country, towns and cities are safer for kids than they've been for decades. Since 1995, the number of children reported missing each year has dropped by 50%, the Federal Bureau of Investigation finds. The vast majority of those cases involved kids running away from home or a parent taking the child without informing the other parent. Despite the drumbeat of fear about kidnappings, only about 100 kids are abducted by strangers each year according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

"We do not think about the statistical probabilities or compare the likelihood of such events with far more present dangers, like increasing rates of childhood diabetes or depression,' Brooks writes in the Times.

How I taught my daughter to run errands

Which brings me back to my daughter perched atop our house on the roof.

I believe that Rosy feels stressed by the physical boundaries imposed on her. That stress causes her to push against these boundaries and misbehave. At age 2, she figured out how to unlock three doors so she could sneak out in the morning and run to a park. Then at age 4, she would climb onto the roof.

In her own way, she was telling me, "Hey, Mamma, I need more autonomy! I need more responsibility. I'm underemployed over here and it doesn't feel good."

And so on the fourth morning of Rosy's rooftop trick, I decided to give her more autonomy and more responsibility by asking her to go to the corner market by herself.

But, and this is key, I didn't simply hand Rosy some money, a grocery bag, close my eyes and send her to the market up the street.

Heeding the advice from parents all over the world, including Tun Burgos in Mexico, I had been training Rosy, step by step over the course of the year, how to handle this task.

So that, by the time I asked her, she had the skills to stay safe and handle problems that arise. (And as you'll see, on the first few trips, she was never alone).

Starting when Rosy was around 3, my husband and I began to teach her how to navigate intersections. We taught her to stop at crosswalks, look for turning cars and, when it's safe, proceed slowly. We crossed together many, many times before, letting her try it in front of us – although just a few feet away. Then we'd watch from a farther distance. Maybe even 50 feet away. Over the course of a year or so, I watched her successfully – and safely – cross intersections dozens, perhaps, even a hundred times. By the time she reached 4, I was confident she had mastered the skill.

During this training time, I also made sure she knew our neighborhood well. I introduced her to neighbors that we knew as well as the clerks who work behind the counter at the market. So she had allies around every corner – and extra eyes keeping her safe.

I also taught her, step-by-step, how to walk our dog – who's a 70-pound German shepherd. At first, Rosy walked the dog just 50 feet from our house. But eventually, over time, she worked her way up to taking the dog to a nearby park about a block away. Through this simple task, she grew comfortable walking around our neighborhood alone, and she also learned how to take "protection" with her.

And when it was finally time for Rosy to go to the market, the first time, she actually didn't go alone. Instead, I did something that Tun Burgos in the Yucatan suggested: I followed her, stealthily, from a distance. "When I let Alexa go [at first] ... I would send one of her sisters to follow," she explained.

For the first few trips to market, I kept an eye on Rosy the whole time. I stayed about 40 feet behind her, hiding behind trash cans and bushes, so she thought she was alone. I watched her cross the street carefully, hitch the dog up to a post outside the market and then buy everything on the grocery list. Seeing her accomplish all these tasks, with thought and skill, gave me the same feeling that I had at the end of "Old Enough!": I thought, Wow, kids are so much more capable than we think! And Wow, American society is really holding them back.

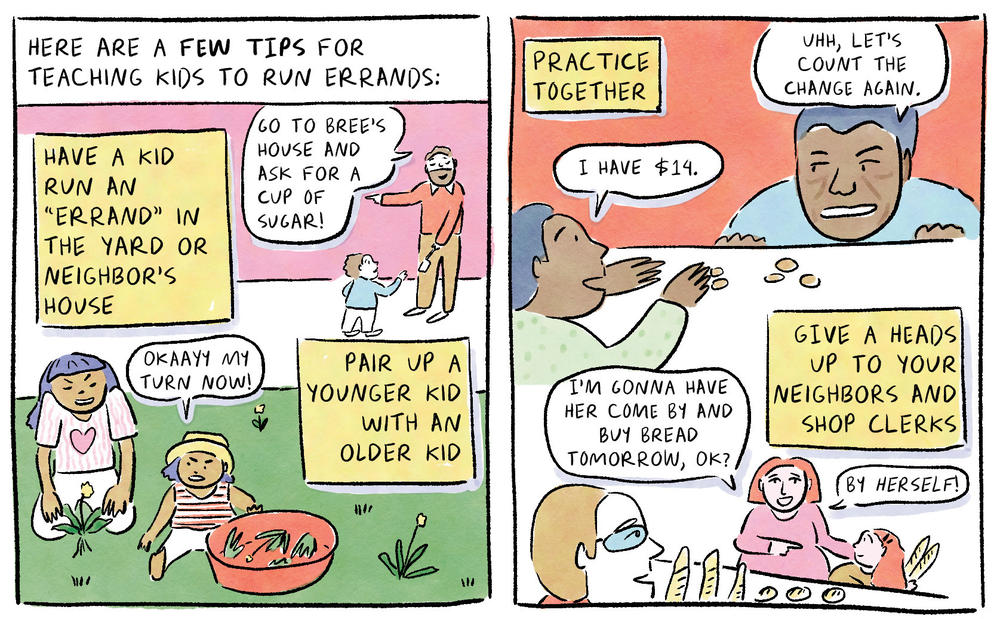

Here are other ways that parents around the world help kids learn to run errands over time, in a stepwise manner, to build confidence and skills:

- Kids run errands in the yard or in front of the house: For young kids, even just going into the back yard or nearby sidewalk to pick herbs or flowers is a huge responsibility. Rosy also likes to take the garbage out to the dumpster, run out to the car to get something we forgot and walk the dog.

- Kids run errands to a neighbor's house: For decades, perhaps centuries, kids in the U.S. have run next door to get a cup of sugar or some butter from a neighbor. And this can be about giving, not just receiving. When I was about 8 years old, my mom would send me door-to-door around our neighborhood, handing out fresh vegetables from our garden.

- Older kids pair up with younger kids: Around the world, siblings often help younger kids stay safe around neighborhood and on errands.

- Prepare neighbors and shop clerks: Before having kids run errands solo, parents acquaint kids with the people who work at the stores, as well as the people they might meet along the way. I also let the market know that Rosy might be coming in to buy some food on her own.

- Break up the tasks into chunks: Even at age 3, Rosy loved to buy groceries. That is, she would pay for them at the checkout under my watchful eye. Eventually, she started going into the market, alone, while I stayed outside. One parent in Maryland, had his young boys, starting around age 6, practice getting change for a $5 bill in stores (back when paper money was more prevalent).

- Practice the errand together as much as needed: Before kids are ready to run errands on their own, they've often completed the task dozens of times with a sibling or their parents.

If your kid is anything like Rosy, they will cherish and love these moments of responsibility and autonomy. I just asked Rosy, now age 6, if she remembers the first time she went to the market "alone." She not only remembered it, she knew exactly how old she was.

"Did you feel scared on the trip?" I asked.

"No," she answered quickly. "It felt fun because you weren't there to boss me around."

And guess what? After that one errand, she stopped going up on the roof.

Your Turn: Did you teach your children to run errands on their own?

Share a personal example. Why did you decide to do it? What were the challenges? Was your community supportive? Send your thoughts in an email to goatsandsoda@npr.org with the subject line "Kids and errands." Please include your name and location. We may feature it in a story on NPR.org. The deadline is Monday, April 25.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Bottom Content