Section Branding

Header Content

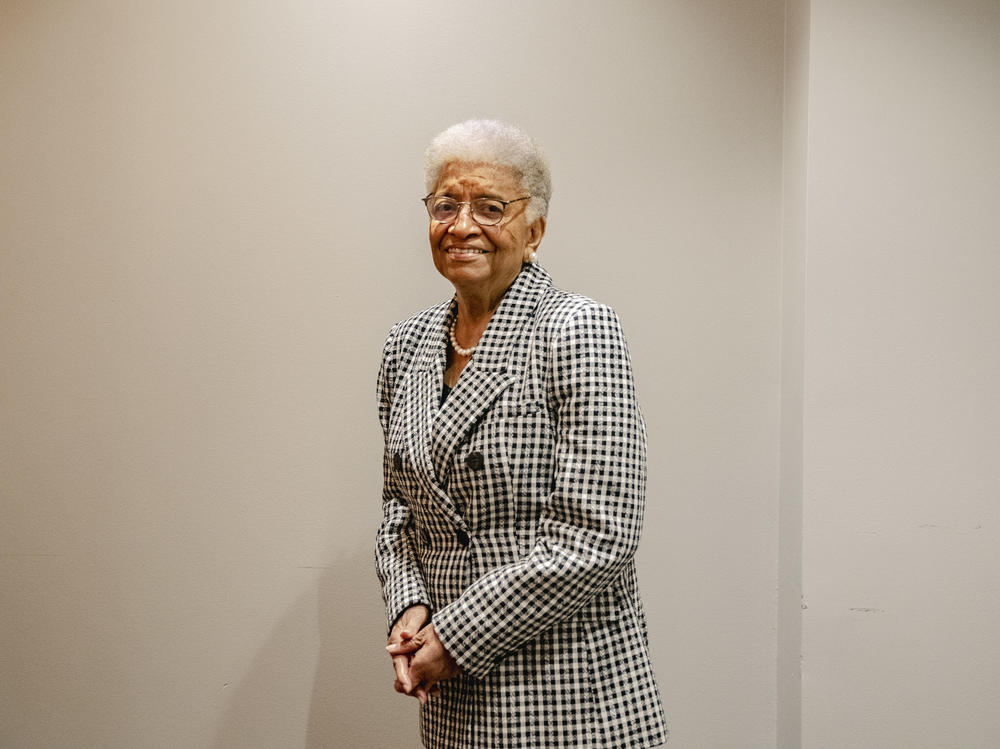

Malaria is making a comeback. Africa's 'Iron Lady' is out to stop it

Primary Content

When I told Ellen Johnson Sirleaf that I have a 4-year-old granddaughter who "knows what she wants and how to get it," she said, "That's the spirit!"

It's a spirit that has characterized the remarkable life of the 83-year-old Liberian, the first democratically elected woman president in Africa and one of three winners of the 2011 Nobel Peace Prize. Known as Africa's "Iron Lady," she was honored for her work to secure women's rights and to give women seats at the table in peace-building after her country's civil war.

Sirleaf's new mission is to bring attention to the fight against malaria. She is in Washington, D.C., today – the officially designated World Malaria Day – to meet with U.S. senators and others in an effort to gain support for anti-malaria efforts.

Her visit comes at a critical time. There were 241 million cases of malaria in 2020, the most recent year for which data are available, up from 227 million cases the year before. Deaths increased, too. The pandemic shoulders much of the blame for hindering access to health care.

The interview has been edited for length.

What gives you the impetus to stay in the public arena?

When you're on a working trail for a long time, it's hard to stop.

And your motivation is ...

To achieve certain improvements, and one of them has to do with my own country and my own continent – to continue to work for the development of Africa.

Do you have personal experience with malaria?

In my childhood. Somewhere between the ages of 10 and 15, I had a case of malaria.

Do you remember how you felt?

Oh, your body weakens, you don't sleep well, you don't eat well.

You were lucky and survived.

I've had friends die from that.

And malaria still persists.

Malaria has existed for so long and affects Africa more than any other infectious disease. Because of COVID-19 the focus on malaria has weakened, and progress addressing malaria has also weakened.

Do you feel as if the world does not pay as much attention to malaria because it is a problem in lower resource countries?

Yes, I do. Health and sanitation facilities are not strong in these countries. That contributes to the growth of mosquitoes. There's lots of response to that but the response is not equal to the threat.

Does it make you angry that malaria seems a forgotten disease?

It makes me concerned and makes me stronger in fight.

Where did you get your spirit of fight?

I had a mother who was strong. Our father [became] ill while we were children. She had to carry the burden. She fed the family, she took care of him, she made sure we got an education. That's the kind of strength that makes a difference. It's not a physical fighting strength but it's a mental strength.

What would it take to vanquish malaria?

You've got to have funding to be able to get the facilities in place and to do the training. It's unfortunate but that's it — it takes money. It takes financial resources and then human resources.

And in this work to beat malaria, the community health worker plays a role.

Who took the tests? Who served the patients in hospitals and clinics? These were community health workers. They didn't have fully specialized training but they carried the responsibility, they were on the front line to recognize symptoms, report it, deliver the aid.

You know they don't get the kind of recognition as a trained specialist [such as a nurse or physician] would, they don't get the compensation consistent with the service they render. In Africa, we recognize this, and we'd like to put the emphasis on training [more] community health workers.

Regarding COVID, there has been much talk of vaccine inequality – the fact that rich nations have ample supplies of vaccine and other countries do not. Does that surprise you?

You answered that pretty quickly.

Self-interest is human nature, isn't it? The richer countries of the world have to put emphasis on their own citizens, and so they sought to vaccinate 100% of their population and that meant that others would be left behind.

This is one time our African corporate sector responded and put up resources to buy vaccines through what is called COVAX [the global vaccine distribution body set up to supply lower income countries).

The COVID vaccine isn't the only new medical breakthrough. There is now an approved vaccine for malaria.

Let's face it the scientists went to work with COVID-19 and got vaccines in record time.

Malaria has existed for decades and there was never a vaccine for malaria [until 2021]. Just think how many people died because there was no attention to it because it was a poor country problem and a poor country disease.

Can I ask: Is the term "poor country" an appropriate description for countries that aren't, well, wealthy.

Let's correct that. It should be low-income countries. If you look at the natural endowment in many of these countries you cannot say they are poor. They are just poorly managed ... or poorly led.

Could we transition and talk politics for a minute? There aren't many women who have been elected president of a country. What advice do you have for women seeking political office?

Women have to be determined to compete. Women have to have a specific goal they want to achieve and ensure that they stay on course with self-confidence. It's going to take effort to break the stereotypes that women face and all the barriers because [it is] a male-dominated world. And [they've] got to be prepared to take criticism as women are always subjected to criticisms, sometimes unfairly.

In your own political career, is there anything you would do differently in retrospect?

I guess I could have locked everybody up for corruption!

It's an honor to interview a Nobel Prize winner. Could you share your memory of getting the news?

I was on a campaign trail, so I wasn't thinking about anything international. I was trying to win my election. I was in a vehicle on a bad road trying to go to a political rally when I got the call.

What did you say to the caller?

Why?

They said, "I can't give you any details. The committee is going to tell you the reason why." I knew it had to do with the many years of managing a war-torn country, bringing credibility to the country, giving hope to the people of Liberia who had lost all hope for two decades.

Did the prize help your campaign?

It did eventually but not right away. People in Liberia were looking to see how was I going to make sure they got a job and their children could go to school. Politics are all local.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.