Section Branding

Header Content

Scientists say they've solved a 700-year-old mystery: Where and when Black Death began

Primary Content

Where did the Black Death come from? And when did it first appear?

As the deadliest pandemic in recorded history – it killed an estimated 50 million people in Europe and the Mediterranean between 1346 and 1353 — it's a question that has plagued scientists and historians for nearly 700 years.

Now, researchers say they've found the genetic ancestor of the Black Death, which today, still infects thousands of people each year. New research, published this month in the journal Nature, provides biological evidence that places the ancestral origins of Black Death in Central Asia, in what is now modern-day Kyrgyzstan.

What's more, the researchers find that the strain from this region "gave rise to the majority of [modern plague] strains circulating in the world today," says Phil Slavin, co-author on the paper and a historian at the University of Stirling in Scotland.

But like many a mystery, this one isn't so easily solved.

A tantalizing lead

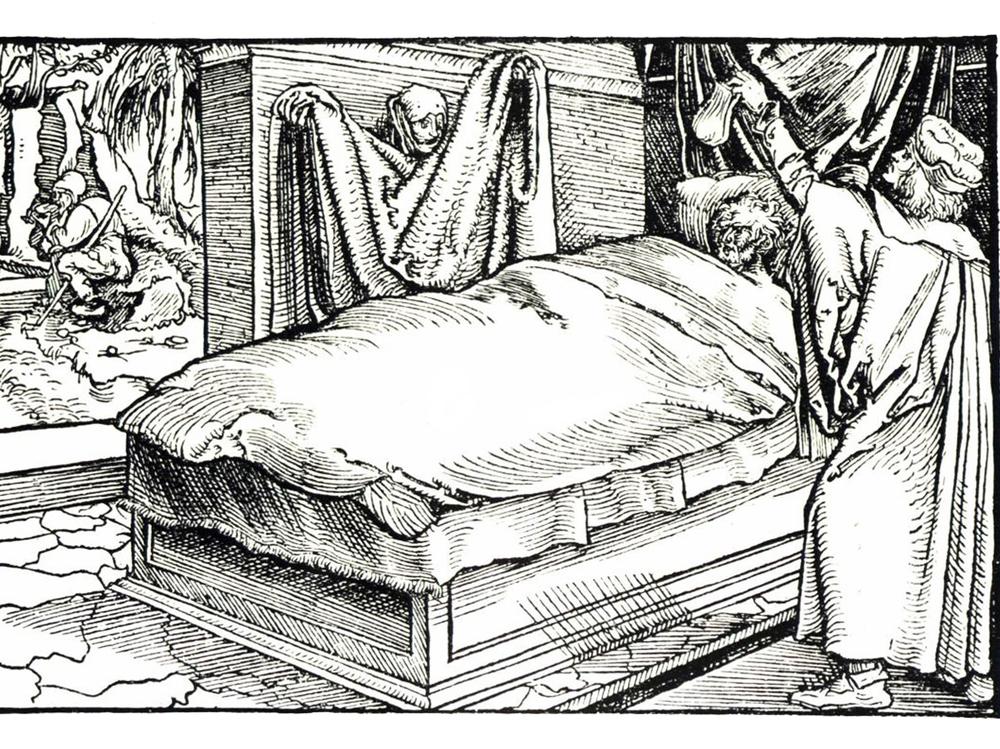

Black Death, a kind of bubonic plague, is one of several strains of plague. It got its frightening name because those infected developed gangrenous, blackened lesions all over their body. The disease is characterized by fever and swelling of the lymph nodes and caused by the bacterium Yesenia pestis, which spreads via rodents carrying infected fleas.

At some point in the past, a single plague strain diversified into four different lineages. In one of those lineages, the strain that caused Black Death evolved. The researchers say that determining just where and when this happened has been a mystery.

Plague researchers around the world have long suspected that the diversification of Y. pestis may have happened in the Tien Shan Mountains near Chüy Valley on the northern border of Kyrgyzstan.

That's because in 1885, researchers found a clue. They discovered two cemeteries in the area that had an unusually high number of tombstones inscribed with dates between 1338 and 1339 — about 8 years before the Black Death pandemic began in Europe.

These tombstones also mentioned the cause of death, mawtānā, the Syriac word for "pestilence." It was an indication that perhaps a plague had swept through the area — and motivation for Slavin and colleagues to delve deeper.

While the tombstone inscriptions were compelling, they weren't enough to prove that the people there really died from plague, say the researchers. Slavin and the team would need genetic evidence.

An ancient DNA test

So the team turned to specialists on ancient DNA to help. "We extracted DNA from human remains that were associated with [the two cemeteries]," explains Maria Spyrou, lead author on the paper and a geneticist at the University of Tübingen in Germany.

Hundreds of bodies from these cemeteries had been removed during excavations between 1885 and 1892 and were housed in the Kunstkamera, the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Spyrou and colleagues procured tooth samples from 7 of the stored bodies. Teeth have lots of blood vessels in them, says Spyrou, making them the most likely place to find evidence of plague, a blood-borne infection, given that the rest of the bodies decayed substantially.

Using ancient DNA sequencing techniques, the team was able to recover traces of DNA from Y. pestis in 3 of the samples. In other words, the researchers were able to confirm that the people who died in Chüy Valley died from plague.

Tracing the strain's lineage

The next step was for the scientists to see how closely related the Chüy Valley strain was to Black Death and other plague strains.

To do that, the team sequenced DNA samples from modern-day plague (they got them from marmots and other rodents in Central Asia) and procured DNA sequences from historical plague, including Black Death, from other studies. They used these sequences to create an evolutionary tree to map out the relationships between the strains and compare them to the strain from Chüy Valley.

The tree revealed that the Chüy Valley strain was different from the Black Death strain by only two mutations. And because the researchers had dates for the Chüy Valley strain, found on the inscriptions of the tombstones, they were able to confirm that the Chüy Valley strain was older than the Black Death strain — and so concluded that Black Death must have evolved from it.

What's more, the evolutionary tree revealed that the Chüy Valley strain was the ancestor of most other plagues around the world. And from this ancestral strain, plague diversified into four major lineages in what researchers call the "Big Bang." Until now, scientists didn't know where or when the "Big Bang" strain originated – but now, they have evidence that it could be from Chüy Valley and the surrounding regions.

Adding to the plague 'origin story'

Does this mean that the mystery of the origin of Black Death has been solved?

"I would be very cautious about stretching it that far," says Hendrik Poinar, evolutionary geneticist and director of the McMaster University Ancient DNA Center in Ontario, Canada, who was not involved in the study. "Pinpointing a date and a specific site for emergence is a nebulous thing to do."

Y. pestis, he explains, evolves very slowly – it has about one mutation every 5 to 10 years. So, it's possible, he says, that the Chüy Valley strain could have come from another part of the region.

At the time, says Poinar, people in Chüy Valley were traders and moved around Central Asia and Europe. They could have picked up the strain on their travels to say, western Europe. And because the strain is slow to mutate, that strain from western Europe would have looked genetically identical to the one in Chüy Valley, making it difficult to tell when and where the strain came from.

Despite this critique, Poinar says the study is significant in understanding the early history of Black Death because it helps answer questions that plague researchers have spent years trying to find out. We now know, he says, "there was plague at that site 10 years prior to the strains that were circulating in western Europe, and I think that's an important part of the plague puzzle."

Max Barnhart is a AAAS Mass Media Fellow and Ph.D. Candidate at the University of Georgia. He is reporting for NPR this summer.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.